(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH, Feb. 14, 2024 – It was a last-ditch effort. For years doctors had tried to keep a patient’s recurrent drug-resistant bacterial blood infection at bay, but it kept coming back and antibiotics were no longer working.

The family agreed to try an experimental treatment that uses viruses to kill bacteria. The patient’s Enterococcus faecium bacterial strain, which had become zombie-like and was almost impossible to treat with currently available antibiotics, was tested against wastewater collected from across the country to find a virus – called a bacteriophage – that scientists theorized would specifically target the drug-resistant bacteria.

It worked so well the patient was able to leave the hospital for a much-anticipated vacation with her family. The case study by University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine scientists is published today in the American Society for Microbiology journal mBio.

“I was pleasantly surprised, but others on our team were, frankly, shocked at how quickly it worked,” said senior author Daria Van Tyne, Ph.D., assistant professor of infectious diseases at Pitt. “Of course, this is what we wanted, what we hoped for. But the patient’s response was so much better than we expected.”

The case study, which required emergency investigational new drug approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), is one of only a handful that have used bacteriophage therapy to treat E. faecium infection. The researchers expect the results from this study will inform future use of the therapy.

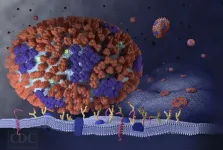

Bacteriophages – known informally as ‘phages’ – are viruses that target and infect bacteria, killing the bacteria as they replicate. Different phages target different bacteria and can be so selective that they only target a specific strain of a bacterium and won’t infect other bacteria or injure human cells. Phages are abundant and can be found everywhere from water and soil to the human body. Wastewater from sewage treatment plants is a common source researchers use to isolate new phages.

Doctors are increasingly interested in phage therapy when all else fails to fight a deadly bacterial infection. But as the therapy is not currently standardized or approved by the FDA, it is not widely available. Several clinical trials – including at Pitt – are underway to confirm its safety and test its efficacy.

The patient in the case study was a 57-year-old woman who had a complex medical history and an autoimmune condition that required immunosuppression to treat. Along the course of her medical journey, drug-resistant E. faecium colonized her gut and spread to her blood, causing recurrent bloodstream infections that required multiple and prolonged hospitalizations between 2013 and 2020. Finally, in late 2020, after a month-long hospitalization, doctors determined that antibiotics were no longer working and suggested phage therapy.

Scientists at the University of Colorado discovered the phage that targeted her bacterial strain and sent it to Pittsburgh where it was grown and prepared in Van Tyne’s lab and then given to the patient alongside antibiotics.

“Phages attack bacteria in a different way than antibiotics,” said lead author Madison Stellfox, M.D., Ph.D., postdoctoral infectious diseases fellow at Pitt. “We believe that the phage therapy worked in tandem with the antibiotics to help the patient fight the infection.”

Within 24 hours of receiving phage therapy, the patient’s blood infection had resolved and she could go home, where she continued the phage and antibiotic combination. She developed a few short-lived breakthrough infections, which indicated the bacteria was getting around the therapy, so the researchers found an additional phage that targeted her bacteria.

With the addition of the new phage, the patient was blood infection-free for four months and able to travel out of state for a for a family beach vacation.

However, just over six months after starting phage therapy, the blood infection returned, and the phage-antibiotic combination was thought to be no longer effective. The patient died in 2022.

In order to learn why the infections recurred despite the combination being previously effective, laboratory testing revealed that the patient’s immune system had likely activated in a way that blocked the phages from attacking the bacteria. Van Tyne and Stellfox suspect that either the addition of the second phage or the increased dose of the phage combination – or both – had prompted the immune response.

“What we learned from this patient and her allowing us to follow and document her medical journey will help future patients,” said Van Tyne. “Phage therapy could be a powerful tool against the ever-growing threat of antibiotic resistance and the data from her case will help shape clinical trials that could one day make it widely available to patients in need.”

Additional authors on this release are Carolyn Fernandes, M.D., Ryan K. Shields, Pharm.D., M.S., Ghady Haidar, M.D., Kailey Hughes Kramer, Ph.D., and Emily Dembinski, all of Pitt, and Mihnea R. Mangalea, Ph.D., Garima Arya, Ph.D., Gregory S. Canfield, M.D., Ph.D., and Breck A. Duerkop, Ph.D., all of the University of Colorado at the time of the work.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (T32AI138954, R01AI165519, R21AI151363, R01AI141479, T32AR007534 and K23AI154546).

# # #

About the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

As one of the nation’s leading academic centers for biomedical research, the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine integrates advanced technology with basic science across a broad range of disciplines in a continuous quest to harness the power of new knowledge and improve the human condition. Driven mainly by the School of Medicine and its affiliates, Pitt has ranked among the top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health since 1998. In rankings released by the National Science Foundation, Pitt is in the upper echelon of all American universities in total federal science and engineering research and development support.

Likewise, the School of Medicine is equally committed to advancing the quality and strength of its medical and graduate education programs, for which it is recognized as an innovative leader, and to training highly skilled, compassionate clinicians and creative scientists well-equipped to engage in world-class research. The School of Medicine is the academic partner of UPMC, which has collaborated with the University to raise the standard of medical excellence in Pittsburgh and to position health care as a driving force behind the region’s economy. For more information about the School of Medicine, see www.medschool.pitt.edu.

END

Case study: drug-resistant bacteria responds to phage-antibiotic combo therapy

2024-02-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

ETRI unveils AI analysis service platform at international e-sports tournament

2024-02-14

ETRI’s researchers have developed an AI-powered e-sports analysis platform that provides real-time win rate prediction services by analyzing gameplay screens. This platform was notably applied to the highly popular League of Legends (LoL) during a recent international e-sports tournament, garnering positive feedback.

Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute (ETRI) has developed a technology that recognizes real-time game situations by analyzing play elements extracted from game videos and automatically generates highlights by identifying key play events in the game.

Also, this e-sports service platform, based ...

Pancreatic cancer hijacks a brain-building protein

2024-02-14

Scientists at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) and the University of California, Davis have reached a new breakthrough in pancreatic cancer research—eight years in the making. It could help slow the disease’s deadly spread.

In 2017, as a postdoc in CSHL’s Tuveson lab, Chang-il Hwang and collaborators from the Vakoc lab uncovered a protein essential for jumpstarting metastasis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Now an assistant professor at UC Davis, Hwang recently reunited with CSHL Professors David Tuveson and Christopher Vakoc. The trio once again set their sights on PDAC. The disease is known for its aggressiveness. ...

Pesticides to help protect seeds can adversely affect earthworms’ health

2024-02-14

While pesticides protect crops from hungry animals, pesky insects, or even microbial infections, they also impact other vital organisms, including bees and earthworms. And today, research published in ACS’ Environmental Science & Technology Letters reveals that worms are affected by the relatively small amounts of chemicals that can leach out of pesticide-treated seeds. Exposure to nonlethal amounts of these insecticides and fungicides resulted in poor weight gain and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage in the worms.

Pesticide treatment can be introduced at several different ...

Discovery of a subset of human short introns that are spliced out by a novel mechanism

2024-02-14

In humans, the length of pre-mRNA varies extensively (from 30 to 1,160,411 nucleotides by recent studies). The fundamental mechanism of splicing has been studied with model pre-mRNAs including 158- and 231-nt introns, for historical instance, that are spliced very efficiently in vitro and in vivo. Such an ideal pre-mRNA contains good splicing signal sequences, i.e., the 5′ splice site, the branch-site (BS) sequence, and the polypyrimidine tract (PPT) followed by the 3′ splice site that are recognized by U1 snRNP, U2 snRNP and U2AF2–U2AF1, respectively. Prof. Mayeda says, “Given the diverse lengths ...

Cold-water coral traps itself on mountains in the deep sea

2024-02-14

Corals searching for food in the cold and dark waters of the deep sea are building higher and higher mountains to get closer to the source of their food. But in doing so, they may find themselves trapped when the climate changes. That is shown in the thesis that theoretical ecologist Anna van der Kaaden of NIOZ in Yerseke and the Copernicus Institute for Sustainable Development in Utrecht will defend on Feb. 20 at the University of Groningen. “When the water gets warmer, these creatures prefer to be deeper, but a coral doesn’t just walk down the mountain,” Van der Kaaden said.

Deep and dark

Unlike the famous, colorful tropical corals, cold-water corals live ...

Cost-effective to routinely change surgical gloves and instruments as well as being safer

2024-02-14

Surgeons who routinely change surgical gloves and instruments are incurring similar costs to those using the same equipment, a new study has found.

The economic evaluation funded by the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) follows a clinical trial conducted at 80 hospitals in Benin, Ghana, India, Mexico, Nigeria, Rwanda, and South Africa which established that routine change of gloves and instruments reduces surgical site infections (SSIs) by 13%.

The evaluation, published by the Lancet Global ...

Scientists discover hidden army of lung flu fighters

2024-02-14

Scientists have long thought of the fluid-filled sac around our lungs merely as a cushion from external damage. Turns out, it also houses potent virus-eating cells that rush into the lungs during flu infections.

Not to be confused with phages, which are viruses that infect bacteria, these cells are macrophages, immune cells produced in the body.

“The name macrophage means ‘big eater.’ They gobble up bacteria, viruses, cancer cells, and dying cells. Really, anything that looks foreign, they take it up and destroy it,” said UC Riverside virologist Juliet Morrison, who led the discovery team. “We were surprised to find them in the lungs ...

USC announces new Leonard D. Schaeffer Institute for Public Policy & Government Service

2024-02-14

USC, together with Leonard and his late wife Pamela Schaeffer, is launching a new institute with a $59 million gift from the Schaeffers to be anchored in Los Angeles and in the university’s new Capital Campus in Washington, D.C. The mission of the Leonard D. Schaeffer Institute for Public Policy & Government Service is to strengthen democracy by training generations of public leaders and advancing evidence-based research to shape policy that addresses the nation’s most pressing issues, USC President Carol Folt announced ...

Nearly 15% of Americans deny climate change is real, AI study finds

2024-02-14

ANN ARBOR—Using social media data and artificial intelligence in a comprehensive national assessment, a new University of Michigan study reveals that nearly 15% of Americans deny that climate change is real.

Scientists have long warned that a warming climate will cause communities around the globe to face increasing risks due to unprecedented levels of flooding, wildfires, heat stress, sea-level rise and more. Though the science is sound—even showing that human-induced, climate-related natural disasters are growing in frequency ...

Red nets signal “stop” to insect pests, reduce need for insecticides

2024-02-14

Red nets are better at keeping away a common agricultural insect pest than typical black or white nets, according to a new study. Researchers experimented with the effect of red, white, black and combination-colored nets on deterring onion thrips from eating Kujo leeks, also called Welsh onions. In both lab and field tests, red nets were significantly better at deterring the insect than other colors. Also, in field tests, onion crops which were either partially or fully covered by red netting required 25-50% less insecticide than was needed for a totally uncovered field. Changing agricultural nets from black or white to red could help reduce pesticide ...