In humans, the length of pre-mRNA varies extensively (from 30 to 1,160,411 nucleotides by recent studies). The fundamental mechanism of splicing has been studied with model pre-mRNAs including 158- and 231-nt introns, for historical instance, that are spliced very efficiently in vitro and in vivo. Such an ideal pre-mRNA contains good splicing signal sequences, i.e., the 5′ splice site, the branch-site (BS) sequence, and the polypyrimidine tract (PPT) followed by the 3′ splice site that are recognized by U1 snRNP, U2 snRNP and U2AF2–U2AF1, respectively. Prof. Mayeda says, “Given the diverse lengths of human introns, it is likely that more than one mechanism exists. This is our motivation to initiate our study of splicing focused on human short introns.”

Dr. Fukumura explains, “Our previous research on the splicing process on short intron revealed that the authentic splicing factor U2AF2 cannot bind to the truncated PPT and then RBM17 is replaced with U2AF to promote splicing. You know, this is reasonable because short introns are often too tight for the sufficient length of PPT. We published this finding in 2021. However, RBM17 cannot bind to the truncated PPT in vitro, so we did not know how the truncated PPT and the following the 3′ splice site are recognized by RRM17. Therefore, we hypothesized that another protein factor is involved in RBM17-dependent splicing.” The Mayeda group eventually identified this protein cofactor behind the RBM17-dependent splicing, which is the SAP30BP. Their study was published in Volume 42, Issue 12 of the journal Cell Reports on December 07, 2023.

Dr. Fukumura states, “It was critical to investigate previous references. From three papers, I was convinced that SAP30BP is the strongest candidate for the cofactor of RBM17.” They showed that the existence of SAP30BP in human early splicing complex, the fruit fly SAP30BP, and RBM17 were detected in fly spliceosome formed on a short intron, and the binding between SAP30BP and RBM17 was indeed detected by yeast two-hybrid analysis. “Nowadays, siRNA-mediated depletion of SAPBP in human cell line is the easy straightforward way to check the repression of RBM17-dependent splicing. And it was bingo!” says Dr. Fukumura.

The transcripts in SAP30BP-depleted human cells were analyzed by a next-generation sequencer (RNA-Seq analysis), and many RBM17- and SAP30BP-dependent introns were found. These introns were distributed in the shorter range and the truncated PPT was indeed a critical determinant of the RBM17/SAP30BP-dependency. Thus, RBM17 and SAP30BP are the general splicing factors.

Prof. Mayeda remarks, “It was a lucky coincidence that Prof. Michael Sattler, who is an expert in structural analyses, was keenly interested in our study, and we could start a productive collaboration.” Protein–protein interactions through UHM (U2AF-homology motif)–ULM(UHM-ligand motif) binding play essential roles in general splicing reactions. The Sattler lab found a hidden ULM sequence in SAP30BP, and demonstrated this was critical to interact with UHM in RBM17 by NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) and ITC (isothermal titration calorimetry) analyses.

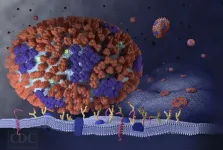

However, the role of RBM17–SAP30BP interaction remained enigmatic. Since RBM17 has only one UHM, the RBM17–SAP30BP binding has to be released before the RBM17 interaction with SF3B1, one component of U2 snRNP, that is essential to promote splicing. So, what is the role of the RBM17–SAP30BP interaction? Prof. Mayeda says, “Fukumura designed a smart binding assay using anti-phospho-SF3B1 antibodies to address this curious question, and we could provide an elegant working model (see IMAGE Figure).” We propose that the intermediary RBM17–SAP30BP complex prevents non-functional RBM17 binding to free unphosphorylated SF3B, which promotes functional RBM17 binding to active phosphorylated SF3B1 on pre-mRNA.

***

Reference

Title of original paper: SAP30BP interacts with RBM17/SPF45 to promote splicing in a subset of human short introns

Journal: Cell Reports

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.113534

About Fujita Health University

Fujita Health University is a private university situated in Toyoake, Aichi, Japan. It was founded in 1964 and houses one of the largest university hospitals in Japan in terms of the number of beds. With over 900 faculty members, the university is committed to providing various academic opportunities to students internationally. Fujita Health University has been ranked eighth among all universities and second among all private universities in Japan in the 2020 Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings. THE University Impact Rankings 2019 visualized university initiatives for sustainable development goals (SDGs). For the “good health and well-being” SDG, Fujita Health University was ranked second among all universities and number one among private universities in Japan. The university became the first Japanese university to host the "THE Asia Universities Summit" in June 2021, and was also the host university in 2022. The university’s founding philosophy is “Our creativity for the people (DOKUSOU-ICHIRI),” which reflects the belief that, as with the university’s alumni and alumnae, current students also unlock their future by leveraging their creativity.

Website: https://www.fujita-hu.ac.jp/en/index.html

About Senior Assistant Professor Kazuhiro Fukumura from Fujita Health University

Dr. Kazuhiro Fukumura is a Senior Assistant Professor at the Division of Gene Expression Mechanism, the Center for Medical Science, Fujita Health University (Aichi, Japan). He earned a Ph.D. degree of Science in 2009 from the Graduate School of Science and Technology at Kobe University, Japan. Since then, he has been performing fundamental research with original ideas in the field of pre-mRNA splicing. He is one of the internationally recognized talented young investigators.

Funding information

The study was partially supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (grant number: 18K07304), (B) (grant number: JP16H04705) and (C) (grant number: JP21K06024) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). Research grants from the Hori Sciences and Arts Foundation, Nitto Foundation, Takeda Science Foundation, and Aichi Cancer Research Foundation were also partially supported this study.

END