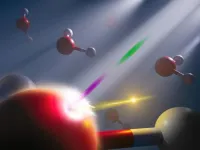

(Press-News.org) RICHLAND, Wash.—In an experiment akin to stop-motion photography, scientists have isolated the energetic movement of an electron while “freezing” the motion of the much larger atom it orbits in a sample of liquid water.

The findings, reported today in the journal Science, provide a new window into the electronic structure of molecules in the liquid phase on a timescale previously unattainable with X-rays. The new technique reveals the immediate electronic response when a target is hit with an X-ray, an important step in understanding the effects of radiation exposure on objects and people.

“The chemical reactions induced by radiation that we want to study are the result of the electronic response of the target that happens on the attosecond timescale,” said Linda Young, a senior author of the research and Distinguished Fellow at Argonne National Laboratory. “Until now radiation chemists could only resolve events at the picosecond timescale, a million times slower than an attosecond. It’s kind of like saying ‘I was born and then I died.’ You’d like to know what happens in between. That’s what we are now able to do.”

A multi-institutional group of scientists from several Department of Energy national laboratories and universities in the U.S. and Germany combined experiments and theory to reveal in real-time the consequences when ionizing radiation from an X-ray source hits matter.

Working on the time scales where the action happens will allow the research team to understand complex radiation-induced chemistry more deeply. Indeed, these researchers initially came together to develop the tools needed to understand the effect of prolonged exposure to ionizing radiation on the chemicals found in nuclear waste. The research is supported by the Interfacial Dynamics in Radioactive Environments and Materials (IDREAM) Energy Frontier Research Center sponsored by the Department of Energy and headquartered at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL).

“Members of our early-career network participated in the experiment, and then joined our full experimental and theoretical teams to analyze and understand the data," said Carolyn Pearce, IDREAM EFRC director and a PNNL chemist. “We couldn’t have done this without the IDREAM partnerships.”

From the Nobel Prize to the field

Subatomic particles move so fast that capturing their actions requires a probe capable of measuring time in attoseconds, a time frame so small that there are more attoseconds in a second than there have been seconds in the history of the universe.

The current investigation builds upon the new science of attosecond physics, recognized with the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physics. Attosecond X-ray pulses are only available in a handful of specialized facilities worldwide. This research team conducted their experimental work at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), located at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, in Menlo Park, Calif, where the local team pioneered the development of attosecond X-ray free-electron lasers.

“Attosecond time-resolved experiments are one of the flagship R&D developments at the Linac Coherent Light Source,” said Ago Marinelli from the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, who, together with James Cryan, led the development of the synchronized pair of X-ray attosecond pump/probe pulses that this experiment used. “It’s exciting to see these developments being applied to new kinds of experiments and taking attosecond science into new directions.”

The technique developed in this study, all X-ray attosecond transient absorption spectroscopy in liquids, allowed them to “watch” electrons energized by X-rays as they move into an excited state, all before the bulkier atomic nucleus has time to move. They chose the liquid water as their test case for an experiment.

“We now have a tool where, in principle, you can follow the movement of electrons and see newly ionized molecules as they’re formed in real-time,” said Young, who is also a professor in the Department of Physics and James Franck Institute at the University of Chicago.

These newly reported findings resolve a long-standing scientific debate about whether X-ray signals seen in previous experiments are the result of different structural shapes, or “motifs,” of water or hydrogen atom dynamics. These experiments demonstrate conclusively that those signals are not evidence for two structural motifs in ambient liquid water.

“Basically, what people were seeing in previous experiments was the blur caused by moving hydrogen atoms,” said Young. “We were able to eliminate that movement by doing all of our recording before the atoms had time to move.”

From simple to complex reactions

The researchers envision the current study as the beginning of a whole new direction for attosecond science.

To make the discovery, PNNL experimental chemists teamed with physicists at Argonne and the University of Chicago, X-ray spectroscopy specialists and accelerator physicists at SLAC, theoretical chemists at the University of Washington, and attosecond science theoreticians from the Hamburg Centre for Ultrafast Imaging and the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science (CFEL), Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY), in Hamburg, Germany.

During the global pandemic, in 2021 and into 2022, the PNNL team used techniques developed at SLAC to spray an ultra-thin sheet of pure water across the X-ray pump pulse path.

“We needed a nice, flat, thin sheet of water where we could focus the X-rays,” said Emily Nienhuis, an early-career chemist at PNNL, who started the project as a post-doctoral research associate. “This capability was developed at the LCLS.” At PNNL, Nienhuis demonstrated that this technique can also be used to study the specific concentrated solutions that are central to the IDREAM EFRC and will be investigated at the next stage of the research.

From experiment to theory

Once the X-ray data had been collected, theoretical chemist Xiaosong Li and graduate student Lixin Lu from the University of Washington applied their knowledge of interpreting the X-ray signals to reproduce the signals observed at SLAC. The CFEL team, led by theoretician Robin Santra, modelled the liquid water response to attosecond X-rays to verify that the observed signal was indeed confined to the attosecond timescale.

“Using the Hyak supercomputer at the University of Washington, we developed a cutting-edge computational chemistry technique that enabled detailed characterization of the transient high-energy quantum states in water,” said Li, the Larry R. Dalton Endowed Chair in Chemistry at the University of Washington and a Laboratory Fellow at PNNL. “This methodological breakthrough yielded a pivotal advancement in the quantum-level understanding of ultrafast chemical transformation, with exceptional accuracy and atomic-level detail.”

Principal Investigator Young originated the study and supervised its execution, which was led on-site by first author and postdoc Shuai Li. Physicist Gilles Doumy, also of Argonne, and graduate student Kai Li of the University of Chicago were part of the team that conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. Argonne’s Center for Nanoscale Materials, a DOE Office of Science user facility, helped characterize the water sheet jet target.

Together, the research team got a peek at the real-time motion of electrons in liquid water while the rest of the world stood still.

“The methodology we developed permits the study of the origin and evolution of reactive species produced by radiation-induced processes, such as encountered in space travel, cancer treatments, nuclear reactors and legacy waste,” said Young.

The study has three co-first authors: S. Li, Lu, and Swarnendu Bhattacharyya of DESY. The three corresponding authors are X. Li, Santra and Young. A full author list is available here.

This work was primarily supported by IDREAM, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences program. Use of the LCLS, the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, and resources from the Center for Nanoscale Materials, Argonne National Laboratory, are supported by the DOE Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences program. Additional support came from DESY and Cluster of Excellence, “CUI: Advanced Imaging of Matter,” of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

# # #

About PNNL

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory draws on its distinguishing strengths in chemistry, Earth sciences, biology and data science to advance scientific knowledge and address challenges in sustainable energy and national security. Founded in 1965, PNNL is operated by Battelle for the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, which is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States. DOE’s Office of Science is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit https://energy.gov/science. For more information on PNNL, visit PNNL's News Center. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and Instagram.

END

First-ever atomic freeze-frame of liquid water

Scientists report the first look at electrons moving in real-time in liquid water; findings open up a whole new field of experimental physics

2024-02-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Superbug killer: New synthetic molecule highly effective against drug-resistant bacteria

2024-02-15

A new antibiotic created by Harvard researchers overcomes antimicrobial resistance mechanisms that have rendered many modern drugs ineffective and are driving a global public health crisis.

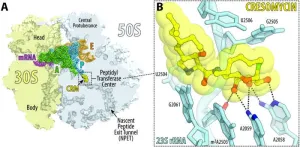

A team led by Andrew Myers, Amory Houghton Professor of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, reports in Science that their synthetic compound, cresomycin, kills many strains of drug-resistant bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

“While we don’t yet know whether cresomycin and drugs like it are safe ...

With just a little electricity, MIT researchers boost common catalytic reactions

2024-02-15

CAMBRIDGE, MA — A simple technique that uses small amounts of energy could boost the efficiency of some key chemical processing reactions, by up to a factor of 100,000, MIT researchers report. These reactions are at the heart of petrochemical processing, pharmaceutical manufacturing, and many other industrial chemical processes.

The surprising findings are reported today in the journal Science, in a paper by MIT graduate student Karl Westendorff, professors Yogesh Surendranath and Yuriy Roman-Leshkov, and two others.

“The results are really striking,” says Surendranath, a professor of chemistry ...

Keeping telomerase in check

2024-02-15

The natural ends of chromosomes appear alarmingly like broken DNA, much as a snapped spaghetti strand is difficult to distinguish from its intact counterparts. Yet every cell in our bodies must have a way of differentiating between the two because the best way to protect the healthy end of a chromosome also happens to be the worst way to repair damaged DNA.

Consider the enzyme telomerase, which is responsible for maintaining protective telomeres at the natural ends of chromosomes. Were telomerase to seal off a broken strand of DNA with a telomere, it would prevent further repair of that break and delete essential genes. Now, a new study in Science describes how cells avoid ...

Competition for food drives the planet’s remaining mass migration of herbivores

2024-02-15

Upending the prevailing theory of how and why multi-species mass-migration patterns occur in Serengeti National Park, researchers from Wake Forest University have confirmed that the millions-strong wildebeest population pushes zebra herds along in competition for the most nutrient-dense grasses.

The study resulting from this research, “Interplay of competition and facilitation in grazing succession by migrant Serengeti herbivores,” appears today in the peer-reviewed journal Science.

For decades, biologists have believed the major grazing ...

UT Dallas Wind Energy Center to expand with new headquarters, resources

2024-02-15

The University of Texas at Dallas’ wind energy research programs have expanded rapidly in recent years, with labs, offices and facilities spread out on campus. In 2020 UT Dallas formed the Wind Energy Center, called UTD Wind, to bring its wind energy programs under one virtual umbrella.

Now, a new initiative will give UTD Wind a physical headquarters for the first time with additional labs, meeting areas and office space. The project also includes additional equipment for wind energy research and education.

UT Dallas has received $1.6 million through the federal Consolidated Appropriations Act to support the expansion, which will bring most of the center’s ...

More Aston University scholarships to encourage graduates from under-represented groups to work in artificial intelligence

2024-02-15

• Eleven scholarships worth £10k each for MSc Applied AI

• They are funded by the Office for Students (OfS)

• Aimed at graduates without a science, tech, engineering or maths degree.

Aston University is offering more opportunities to graduates who want a career in artificial intelligence (AI) but don’t have a science, technology, engineering or maths degree.

The scholarships are offered due to increased funding from the Office for Students (OfS). Each award is worth £10,000 and will be awarded to students enrolling ...

How is deforested land in Africa used?

2024-02-15

Africa's forested areas – an estimated 14 % of the global forest area – are continuing to decline at an increasing rate – mostly because of human activities to convert forest land for economic purposes. As natural forests are important CO2 and biodiversity reservoirs, this development has a significant impact on climate change and effects the integrity of nature. To intervene in a targeted manner in the interests of climate protection and biodiversity, there has been a lack of sufficiently good data and detailed knowledge ...

Studies with more diverse teams of authors get more citations

2024-02-15

Diverse research is more impactful in the business management field, with female influence growing stronger in the past decade, finds a new study from the University of Surrey.

The study analysed all articles published in the last 10 years (January 2012 to December 2022) in the influential Journal of Management Studies.

The empirical analysis examined three key aspects of teams’ diversity:

Internationality (how international is mix of authors),

Interdisciplinarity (how many different fields of study they come from),

Gender ...

UC Irvine researcher co-authors ‘scientists’ warning’ on climate and technology

2024-02-15

Irvine, Calif., Feb. 15, 2024 – Throughout human history, technologies have been used to make peoples’ lives richer and more comfortable, but they have also contributed to a global crisis threatening Earth’s climate, ecosystems and even our own survival. Researchers at the University of California, Irvine, the University of Kansas and Oregon State University have suggested that industrial civilization’s best way forward may entail embracing further technological advancements but doing so with greater awareness of their potential drawbacks.

In a paper titled “Scientists’ Warning on Technology,” published recently in the Journal of Cleaner ...

Methane emissions from wetlands increase significantly over high latitudes

2024-02-15

– By Julie Bobyock

Wetlands are Earth’s largest natural source of methane, a potent greenhouse gas that is about 30 times more powerful than carbon dioxide at warming the atmosphere. A research team from the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) analyzed wetland methane emissions data across the entire Boreal-Arctic region and found that these emissions have increased approximately nine percent since 2002.

Livestock and fossil fuel production are well studied for their role in releasing tons of methane per year into the atmosphere. Although more uncertain, quantifying natural wetlands emissions is important to predicting climate ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

High risk of readmission and death among heart failure patients

Code for Earth launches 2026 climate and weather data challenges

Three women named Britain’s Brightest Young Scientists, each winning ‘unrestricted’ £100,000 Blavatnik Awards prize

Have abortion-related laws affected broader access to maternal health care?

Do muscles remember being weak?

Do certain circulating small non-coding RNAs affect longevity?

How well are international guidelines followed for certain medications for high-risk pregnancies?

New blood test signals who is most likely to live longer, study finds

Global gaps in use of two life-saving antenatal treatments for premature babies, reveals worldwide analysis

Bug beats: caterpillars use complex rhythms to communicate with ants

High-risk patients account for 80% of post-surgery deaths

Celebrity dolphin of Venice doesn’t need special protection – except from humans

Tulane study reveals key differences in long-term brain effects of COVID-19 and flu

The long standing commercialization challenge of lithium batteries, often called the dream battery, has been solved.

New method to remove toxic PFAS chemicals from water

The nanozymes hypothesis of the origin of life (on Earth) proposed

Microalgae-derived biochar enables fast, low-cost detection of hydrogen peroxide

Researchers highlight promise of biochar composites for sustainable 3D printing

Machine learning helps design low-cost biochar to fight phosphorus pollution in lakes

Urine tests confirm alcohol consumption in wild African chimpanzees

Barshop Institute to receive up to $38 million from ARPA-H, anchoring UT San Antonio as a national leader in aging and healthy longevity science

Anion-cation synergistic additives solve the "performance triangle" problem in zinc-iodine batteries

Ancient diets reveal surprising survival strategies in prehistoric Poland

Pre-pregnancy parental overweight/obesity linked to next generation’s heightened fatty liver disease risk

Obstructive sleep apnoea may cost UK + US economies billions in lost productivity

Guidelines set new playbook for pediatric clinical trial reporting

Adolescent cannabis use may follow the same pattern as alcohol use

Lifespan-extending treatments increase variation in age at time of death

From ancient myths to ‘Indo-manga’: Artists in the Global South are reframing the comic

Putting some ‘muscle’ into material design

[Press-News.org] First-ever atomic freeze-frame of liquid waterScientists report the first look at electrons moving in real-time in liquid water; findings open up a whole new field of experimental physics