(Press-News.org) Longstanding challenges in biomedical research such as monitoring brain chemistry and tracking the spread of drugs through the body require much smaller and more precise sensors. A new nanoscale sensor that can monitor areas 1,000 times smaller than current technology and can track subtle changes in the chemical content of biological tissue with sub-second resolution, greatly outperforming standard technologies.

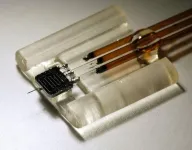

The device, developed by researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, is silicon-based and takes advantage of techniques developed for microelectronics manufacturing. The small device size enables it to collect chemical content with close to 100% efficiency from

highly localized regions of tissue in a fraction of a second. The capabilities of this new nanodialysis device are reported in the journal ACS Nano.

“With our nanodialysis device, we take an established technique and push it into a new extreme, making biomedical research problems that were impossible before quite feasible now,” said Yurii Vlasov, a U. of I. electrical & computer engineering professor and a co-lead of the study.

“Moreover, since our devices are made on silicon using microelectronics fabrication techniques, they can be manufactured and deployed on large scales.”

From micro- to nanodialysis

Nanodialysis is based on a technique called microdialysis in which a probe with a thin membrane is inserted into biological tissue. Chemicals pass through the membrane into a fluid that is pumped away for analysis. The ability to directly sample from tissue has made a major impact in fields like neuroscience, pharmacology and dermatology.

Traditional microdialysis has limitations, though. The probes sample from a few square

millimeters, so they can only measure the average composition over relatively large regions in the tissue. The large size also results in some degree of tissue damage when the probe is inserted, potentially skewing the analysis results. Finally, the fluid pumped through the probe flows at a comparatively high rate, impacting the efficiency and accuracy with which chemical concentrations can be read.

“Many problems with traditional microdialysis can be solved by using a much smaller device,” Vlasov said. “Going smaller with nanodialysis means more precision, less damage from the tissue placement, chemically mapping the tissue with higher spatial resolution, and a much faster readout time allowing a more detailed picture of the changes in tissue chemistry.”

Slow and steady

The most important feature of nanodialysis is the ultra-slow flow rate of the fluid pumped

through the probe. By making the flow rate 1,000 times slower than traditional microdialysis, the device captures the chemical composition of the tissue collected from an area 1,000 times smaller than traditional techniques while maintaining 100% efficiency.

“By drastically decreasing the flow rate, it allows the chemicals diffusing into the probe to match the concentrations outside in the tissue,” Vlasov explained. “Imagine you’re adding dye to a pipe with flowing water. If the flow is too fast, the dye gets diluted to concentrations that are difficult to detect. To avoid dilution, you need to turn the water almost all the way down.”

Silicon fabrication and production

Standard microdialysis devices are constructed using glass probes and polymer membranes, making them a challenge to miniaturize. To build devices suitable for nanodialysis, the researchers used techniques developed for electronic chip manufacturing to create a device based on silicon.

“In addition to enabling us to go smaller, silicon technology makes the devices cheaper,” Vlasov said. “By putting in the time and effort to develop a fabrication process for building our nanodevices on silicon, it is now very straightforward to manufacture them at industrial scales at an incredibly low cost.”

***

Rashid Bashir, a U. of I. bioengineering professor and the dean of The Grainger College of

Engineering, co-led the project.

These results are published in the ACS Nano article “Highly localized chemical sampling at sub-second temporal resolution enabled with a silicon nanodialysis platform at exceedingly slow flows.” DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.3c09776

Support was provided by the National Institutes of Health’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies Initiative.

END

Vlasov and Bashir groups develop nanoscale device for brain chemistry analysis

2024-02-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

MD Anderson researchers receive over $25.5 million in CPRIT funding

2024-02-21

HOUSTON ― The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center today was awarded 16 grants totaling over $25.5 million from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) in support of cancer screening, early detection and prevention programs, faculty recruitment, and groundbreaking cancer research across all areas of the institution.

“We are grateful for CPRIT’s continued funding of impactful cancer research and prevention programs at MD Anderson, which propels our efforts to deliver new breakthroughs and to advance our mission to end cancer,” said Peter WT Pisters, M.D., president of MD Anderson. “These efforts are pivotal to our institutional strategy ...

Hippo signaling pathway gives new insight into systemic sclerosis

2024-02-21

Systemic sclerosis causes the skin to tighten and harden resulting in a potentially fatal autoimmune condition that is associated with lung fibrosis and kidney disease.

University of Michigan Health researchers have studied the pathology of systemic sclerosis to understand better the disease and identify key pathways in the disease process that can be targeted therapeutically.

A research team led by University of Michigan Health’s Dinesh Khanna, M.B.B.S., M.Sc., professor of rheumatology and Johann Gudjonsson, M.D., Ph.D., professor of dermatology, ...

Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats has long been in flux

2024-02-21

It has been long assumed that Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats was formed as its ancient namesake lake dried up 13,000 years ago. But new research from the University of Utah has gutted that narrative, determining these crusts did not form until several thousand years after Lake Bonneville disappeared, which could have important implications for managing this feature that has been shrinking for decades to the dismay of the racing community and others who revere the saline pan 100 miles west of Salt ...

UM School of Medicine receives $10.6 million in state funding for Abortion Clinical Care Training Program

2024-02-21

A $10.6 million training grant has been awarded to the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) and University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB) to administer Maryland’s Abortion Clinical Care Training Program. The grant will be used to expand the number of healthcare professionals with abortion care training, increase the racial and ethnic diversity among health care professionals with abortion care education, and support the identification of clinical sites needing training.

“Our training will target a major ...

Outsmarting chemo-resistant ovarian cancer

2024-02-21

· Most women with ovarian cancer develop resistance to chemotherapy

· Nanoparticle fools cancer cells and prevents cholesterol from entering

· More than 18,000 women a year die from ovarian cancer

CHICAGO --- Women diagnosed with ovarian cancer may initially respond well to chemotherapy, but the majority of them will develop resistance to treatment and die from the disease.

Now Northwestern Medicine scientists have discovered the Achilles heel of chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer — its hunger for cholesterol — and how to sneakily use that to destroy it.

In a new study, scientists first showed that chemotherapy-resistant ...

Does Russia stand to benefit from climate change?

2024-02-21

“There’s a narrative out there about climate change that says there are winners and losers. Even if most of the planet might lose from the changing climate, certain industries and countries stand to benefit. And Russia is usually at the tip of people’s tongues, with Russian officials even making the claim that Russia is a potential winner.”

This portrayal, described by Debra Javeline, associate professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame and lead author on the recently published study “Russia in a changing climate,” was debated ...

Researchers find possible solutions to reverse Alzheimer’s Disease impact

2024-02-21

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill researchers have developed a new drug delivery platform that harnesses helical amyloid fibers designed to untwist and release drugs in response to body temperatures.

A new research paper published on Jan. 26 in Nature Communications reveals groundbreaking structural details into how diseases form much like Alzheimer’s disease. With this knowledge, the group may have uncovered a unique mechanism to reverse both the deposits and their impact on those suffering from these conditions.

UNC-Chapel Hill researcher Ronit Freeman ...

A Mount Sinai-led study shows early success of a novel drug in treating a rare and chronic blood cancer

2024-02-21

New York, NY (February 21, 2024) – A novel treatment for polycythemia vera, a potentially fatal blood cancer, demonstrated the ability to control overproduction of red blood cells, the hallmark of this malignancy and many of its debilitating symptoms in a multi-center clinical trial led by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

In the phase 2 study, the drug rusfertide limited excess production of red blood cells, the main manifestation of polycythemia vera, over the 28-week course of ...

Muscle as a heart-health predictor

2024-02-21

Body composition — often expressed as the amount of fat in relation to muscle — is one of the standard predictors of cardiac health. Now, new research from the University of California San Diego indicates more muscle doesn’t automatically mean lower risk of heart trouble.

The study, published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, found all muscle isn’t the same. Britta Larsen, PhD, says men with a higher area of abdominal muscle have a greater risk of cardiac trouble. It’s a completely different ...

Air pollution linked to more signs of Alzheimer’s in brain

2024-02-21

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE UNTIL 4 P.M. ET, WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 21, 2024

MINNEAPOLIS – People with higher exposure to traffic-related air pollution were more likely to have high amounts of amyloid plaques in their brains associated with Alzheimer’s disease after death, according to a study published in the February 21, 2024, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology. Researchers looked at fine particulate matter, PM2.5, which consists of pollutant particles of less than 2.5 microns in diameter suspended in air.

The study does not prove that air pollution causes more amyloid plaques in the brain. It only ...