BU researchers describe new technological platform to accelerate drug development

2024-02-26

(Press-News.org) EMBARGOED by Cell until 11 am ET Feb. 26, 2024

Contact: Gina DiGravio, 617-358-7838, ginad@bu.edu

BU Researchers Describe New Technological Platform to

Accelerate Drug Development

(Boston)— Drug development is currently an extremely long, expensive and inefficient process. Findings generated in a lab are often very hard to replicate once translated into animal models or in humans.

A family of pharmacological targets, on which approximately 35% of FDA-approved drugs work, consists of receptors at the surface of cells named “G protein coupled receptors” or GPCRs. These membrane proteins sense a wide variety of signals from outside the cell, from hormones to neurotransmitters, or light and odors, to trigger responses of cells, from immune reactions to muscle contraction.

In a new study, researchers at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine describe the development of a new technological platform that will enhance the accuracy and efficiency of drug discovery related to a large family of important pharmacological targets, i.e., GPCRs, allowing it to obtain information that was previously unattainable.

“The new technological platform are biosensors that allow us to detect the activity of GPCRs in their native cellular context and in real time not only with unprecedented fidelity, but also with relative ease. A novelty of this platform is that it is easy for others to implement and that it has been made readily available through a public repository such as open-source,” explains Remi Janicot, first author of the study and a PhD student in the laboratory of Mikel Garcia-Marcos, PhD, professor of biochemistry and cell biology at the school.

The researchers used molecular engineering to create these biosensors, artificial genes that, once expressed as proteins in cells, could detect the activation of very specific cellular responses in real time. The researchers then showed that these biosensors could be leveraged to characterize how many different natural ligands and synthetic drugs change cell responses when the act on the large GPCR class of receptors.

According to the researchers, the biosensor platform described could accelerate drug development for any disease in which GPCRs are implicated, which is a virtually endless list covering neurodegenerative disorders, cancers, cardiovascular diseases, obesity, or asthma, to name a few. “For example, the ongoing interest in developing safer opioid or non-opioid analgesics would benefit from the features of the technology described in our work. Similarly, there is tremendous interest in developing orally bioavailable substitutes for the anti-obesity drugs commercialized as Ozempic and Wegovy, which would also benefit from the technology we described,” said Garcia-Marcos.

The researchers hope the tools developed in this study will transform how the field of pharmacology and drug development approaches the investigation of a large and important class of targets. “Since medicines acting on these targets are already part of everyday life, we see great potential on accelerating the discovery of improved drugs for many different indications, from analgesia to anti-obesity drugs,” added first author and PhD student Remi Janicot.

These findings appear online in the journal Cell.

Funding was provided by NIH grant R01GM147931 (to MG-M) and grant R01NS117101 (to MG-M). RJ is supported by a Predoctoral Fellowship from the American Heart Association (898932). AL is supported by a F31 Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA Predoctoral Fellowship (F31NS115318). JZ was supported by a Dahod International Scholar Award. HZ was supported by the American Heart Association (23CDA1050577).

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2024-02-26

One of the most striking examples of gut plasticity can be observed in animals that are exposed to prolonged periods of fasting, such as hibernating animals or phyton snakes that goes for months without eating, where the gut shrinks with as much as 50%, but recovers in size following a few days of re-feeding. Importantly, the capacity of the gut to undergo resizing is broadly conserved. Hence, in humans, an increase in gut size is observed during pregnancy, which facilitates the uptake of nutrients to support the growth of the fetus.

The Colombani Andersen ...

2024-02-26

What if it were possible to use a scientific model to predict hate crimes, protests, or conflict? Researchers at McGill University and University of Toronto have begun the groundwork to develop a formal predictive model of prejudice, similar to meteorological weather predictions.

The model can be explained by the equation: Prejudice = Threat – Contact + Identification, “with some numbers involved,” says lead author Eric Hehman, Associate Professor in the Department of Psychology and lead author of a new study published in Psychological ...

2024-02-26

Imagine a world where your smartphone can detect your mood just by the way you type a message or the tone of your voice. Picture a car that adjusts its music playlist based on your stress levels during rush hour traffic. These scenarios are not just futuristic fantasies. They are glimpses into the rapidly evolving field of affective computing. Affective computing is a multidisciplinary field integrating computer science, engineering, psychology, neuroscience and other related disciplines. A new and comprehensive review on affective computing was published Jan. 5 in Intelligent ...

2024-02-26

AI decision-making is now common in self-driving cars, patient diagnosis and legal consultation, and it needs to be safe and trustworthy. Researchers have been trying to demystify complex AI models by developing interpretable and transparent models, collectively known as explainable AI methods or XAI methods. A research team offered their insight specifically into audio XAI models in a review article published Jan. 23 in Intelligent Computing, a Science Partner Journal.

Although audio tasks are less researched than visual tasks, their expressive power is not less important. Audio signals are easy to understand and communicate, as they typically depend less on expert explanations ...

2024-02-26

JMIR Publications is pleased to announce a new theme issue in JMIR Neurotechnology exploring brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) that represent the transformative convergence of neuroscience, engineering, and technology. The peer-reviewed journal aims to bridge the gap between clinical neuroscience and information technology by providing a platform for applied human research in the field of neurology.

JMIR Neurotechnology welcomes submissions from scientists, clinicians, and technologists. PhD students and early career researchers are ...

2024-02-26

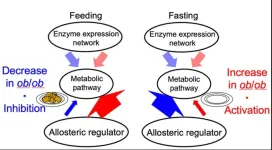

Your liver plays a vital role in your metabolism, the biological process which converts food into energy. We know that being overweight can negatively affect metabolic activity, but not exactly how. To better understand this, researchers compared the livers of mice which were a typical weight with mice which were obese. They were surprised to find that biological regulation of metabolic activity, after a period of feasting and fasting, was reversed between them. In typical mice, allosteric regulation (the process which controls metabolism) was inhibited during feeding and activated when fasting. However, ...

2024-02-26

Striped marlin are some of the fastest animals on the planet and one of the ocean’s top predators. When hunting in groups, individual marlin will take turns attacking schools of prey fish one at a time. Now a new study reported in the journal Current Biology on February 5 helps to explain how they might coordinate this turn-taking style of attack on their prey to avoid injuring each other. The key, according to the new work, is rapid color changes.

“We documented for the first time rapid color change in a group-hunting predator, the striped marlin, as groups of marlin hunted schools of sardines,” says Alicia Burns of Humboldt University ...

2024-02-26

When a star like our Sun reaches the end of its life, it can ingest the surrounding planets and asteroids that were born with it. Now, using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (ESO’s VLT) in Chile, researchers have found a unique signature of this process for the first time — a scar imprinted on the surface of a white dwarf star. The results are published today in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“It is well known that some white dwarfs — slowly cooling embers of stars like our Sun — are ...

2024-02-26

About The Study: This survey study found that primary care pediatricians felt less prepared to manage adolescents’ opioid use disorder (OUD) than alcohol, cannabis, or e-cigarette use and were more likely to refer them to offsite care. These results reveal an opportunity for greater workforce training in line with a 2019 survey showing fewer than 1 in 3 pediatric residency programs included education on prescribing OUD medications.

Authors: Scott E. Hadland, M.D., M.P.H., M.S., of Mass General for Children in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The ...

2024-02-26

About The Study: The findings of this study of 8,988 preadolescent children suggest that the increased risk of suicide attempts, consistently reported for adolescents and adults who smoke cigarettes, extends to a range of emerging tobacco products and manifests among elementary school–aged children. Further investigations are imperative to clarify the underlying mechanisms and to implement effective preventive policies for children.

Authors: Phil H. Lee, Ph.D., of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] BU researchers describe new technological platform to accelerate drug development