(Press-News.org) The tone and tuning of musical instruments has the power to manipulate our appreciation of harmony, new research shows. The findings challenge centuries of Western music theory and encourage greater experimentation with instruments from different cultures.

According to the Ancient Greek philosopher Pythagoras, ‘consonance’ – a pleasant-sounding combination of notes – is produced by special relationships between simple numbers such as 3 and 4. More recently, scholars have tried to find psychological explanations, but these ‘integer ratios’ are still credited with making a chord sound beautiful, and deviation from them is thought to make music ‘dissonant’, unpleasant sounding.

But researchers from Cambridge University, Princeton and the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, have now discovered two key ways in which Pythagoras was wrong.

Their study, published in Nature Communications, shows that in normal listening contexts, we do not actually prefer chords to be perfectly in these mathematical ratios.

“We prefer slight amounts of deviation. We like a little imperfection because this gives life to the sounds, and that is attractive to us,” said co-author, Dr Peter Harrison, from Cambridge University’s Faculty of Music and Director of its Centre for Music and Science.

The researchers also found that the role played by these mathematical relationships disappears when you consider certain musical instruments that are less familiar to Western musicians, audiences and scholars. These instruments tend to be bells, gongs, types of xylophones and other kinds of pitched percussion instruments. In particular, they studied the ‘bonang’, an instrument from the Javanese gamelan built from a collection of small gongs.

“When we use instruments like the bonang, Pythagoras's special numbers go out the window and we encounter entirely new patterns of consonance and dissonance,” Dr Harrison said.

“The shape of some percussion instruments means that when you hit them, and they resonate, their frequency components don’t respect those traditional mathematical relationships. That's when we find interesting things happening.”

“Western research has focused so much on familiar orchestral instruments, but other musical cultures use instruments that, because of their shape and physics, are what we would call ‘inharmonic’.

The researchers created an online laboratory in which over 4,000 people from the US and South Korea participated in 23 behavioural experiments. Participants were played chords and invited to give each a numeric pleasantness rating or to use a slider to adjust particular notes in a chord to make it sound more pleasant. The experiments produced over 235,000 human judgments.

The experiments explored musical chords from different perspectives. Some zoomed in on particular musical intervals and asked participants to judge whether they preferred them perfectly tuned, slightly sharp or slightly flat. The researchers were surprised to find a significant preference for slight imperfection, or ‘inharmonicity’. Other experiments explored harmony perception with Western and non-Western musical instruments, including the bonang.

Instinctive appreciation of new kinds of harmony

The researchers found that the bonang’s consonances mapped neatly onto the particular musical scale used in the Indonesian culture from which it comes. These consonances cannot be replicated on a Western piano, for instance, because they would fall between the cracks of the scale traditionally used.

“Our findings challenge the traditional idea that harmony can only be one way, that chords have to reflect these mathematical relationships. We show that there are many more kinds of harmony out there, and that there are good reasons why other cultures developed them,” Dr Harrison said.

Importantly, the study suggests that its participants – not trained musicians and unfamiliar with Javanese music – were able to appreciate the new consonances of the bonang’s tones instinctively.

“Music creation is all about exploring the creative possibilities of a given set of qualities, for example, finding out what kinds of melodies can you play on a flute, or what kinds of sounds can you make with your mouth,” Harrison said.

“Our findings suggest that if you use different instruments, you can unlock a whole new harmonic language that people intuitively appreciate, they don’t need to study it to appreciate it. A lot of experimental music in the last 100 years of Western classical music has been quite hard for listeners because it involves highly abstract structures that are hard to enjoy. In contrast, psychological findings like ours can help stimulate new music that listeners intuitively enjoy.”

Exciting opportunities for musicians and producers

Dr Harrison hopes that the research will encourage musicians to try out unfamiliar instruments and see if they offer new harmonies and open up new creative possibilities.

“Quite a lot of pop music now tries to marry Western harmony with local melodies from the Middle East, India, and other parts of the world. That can be more or less successful, but one problem is that notes can sound dissonant if you play them with Western instruments.

“Musicians and producers might be able to make that marriage work better if they took account of our findings and considered changing the ‘timbre’, the tone quality, by using specially chosen real or synthesised instruments. Then they really might get the best of both worlds: harmony and local scale systems.”

Harrison and his collaborators are exploring different kinds of instruments and follow-up studies to test a broader range of cultures. In particular, they would like to gain insights from musicians who use ‘inharmonic’ instruments to understand whether they have internalised different concepts of harmony to the Western participants in this study.

Reference

R. Marjieh, P.M.C. Harrison, H. Lee, F. Deligiannaki, & N. Jacoby, ‘Timbral effects on consonance disentangle psychoacoustic mechanisms and suggest perceptual origins for musical scales’, Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-45812-z

Media contacts

Tom Almeroth-Williams, Communications Manager (Research), University of Cambridge: researchcommunications@admin.cam.ac.uk / tel: +44 (0) 7540 139 444

Dr Peter Harrison, University of Cambridge: pmch2@cam.ac.uk

END

Pythagoras was wrong: there are no universal musical harmonies, new study finds

2024-02-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers uncover new clues about links between parent age and congenital disorders

2024-02-27

A new paper in Genome Biology and Evolution, published by Oxford University Press, finds that the link between paternal age and rare congenital disorders is more complex than scientists had previously thought. While researchers have long realized that older fathers are more likely to have children with bone and heart malformations, such as Achondroplasia, Apert, or Noonan syndrome or neurodevelopmental disorders, schizophrenia, and autism, new examination indicates that while the link between some pathogenic mutations increases with paternal age, others do not and may even occur in the father’s testis before sexual maturity.

Delayed fatherhood results in a higher ...

Study reveals parental smoking and childhood obesity link transcends socio-economic boundaries

2024-02-27

A study into parental smoking and childhood obesity has challenged previous notions by revealing that the links between the two are not confined to a specific socio-economic group.

The data shows a strong correlation between parents who smoke and their children’s consumption of high calorie unhealthy foods and drinks, across social classes.

Using longitudinal data on 5,000 Australian children collected over a 10-year period, the research found those living with parents who smoke, on average, eat less healthy, higher calorie food such as fruit juice, sausages, fries, snacks, full fat milk products, ...

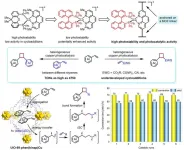

HKU chemists pave the way for sustainable organic synthesis with innovative heterogeneous copper photocatalysis, enabling efficient production of diverse bioactive compounds

2024-02-27

Professor Jian HE, from the Department of Chemistry at The University of Hong Kong (HKU), has spearheaded a research endeavour aimed at revolutionising organic synthesis. His research team has successfully developed a novel heterogeneous copper photocatalyst that enables the efficient formation of cyclobutane rings, a crucial structural element in a vast array of bioactive molecules. Cyclobutane rings are prominently featured in pharmaceuticals, natural products, and various biologically active compounds. By enabling researchers to construct these rings easily and selectively, ...

Using multimodal deep learning to detect malicious traffic with noisy labels

2024-02-27

The success of a deep learning-based network intrusion detection systems (NIDS) relies on large-scale, labeled, realistic traffic. However, automated labeling of realistic traffic, such as by sand-box and rule-based approaches, is prone to errors, which in turn affects deep learning-based NIDS.

To solve the problems, a research team led by Yuefei ZHU published their new research on 15 Feb 2024 in Frontiers of Computer Science co-published by Higher Education Press and Springer Nature.

The team ...

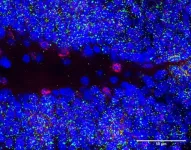

Learning and memory problems in down syndrome linked to alterations in genome's ‘dark matter’

2024-02-27

Researchers at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) reveal that the Snhg11 gene is critical for the function and formation of neurons in the hippocampus. Experiments with mice and human tissues revealed the gene is less active in brains with Down syndrome, potentially contributing to the memory deficits observed in people living with the condition. The findings are published today in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

Traditionally, much of the focus in genomics has been on protein-coding genes, which in humans constitutes around just 2% of the entire genome. The rest is "dark ...

Race, racism, and covid-19 in the US: lessons not learn

2024-02-27

In The BMJ today, Keisha Bentley-Edwards at Duke University, North Carolina, and colleagues argue that systemic racism and economic inequality are at the root of disparity in covid-19 outcomes and suggest how to distribute resources more equitably.

The article is part of a series that highlights the lessons that can be learned from the US’s covid-19 experience and the actions that are needed to prevent the loss of another million citizens in the next pandemic and improve and protect population health.

"Rather than waiting for the next pandemic to address systemic failures, the ...

Low-Temperature Plasma used to remove E. coli from hydroponically grown crops

2024-02-27

A group led by researchers at Nagoya University and Meijo University in Japan has developed a disinfection technology that uses low-temperature plasma generated by electricity to cultivate environmentally friendly hydroponically grown crops. This innovative technology sterilizes the crops, promoting plant growth without the use of chemical fertilizers. Their findings appeared in Environmental Technology & Innovations.

In hydroponic agriculture, farmers cultivate plants by providing their roots with a nutrient solution. However, the nutrient solution can become infected with pathogenic E. coli strains, contaminating the crop and leading to foodborne illnesses.

To avoid ...

UK cancer treatment falls behind other countries

2024-02-27

Two major studies part-funded by Cancer Research UK reveal that the use of chemotherapy and radiotherapy in the UK has lagged behind comparable countries in the past decade

Patients faced longer waits to begin key cancer treatment, which could be impacting people’s chances of survival in the UK

With an upcoming UK general election, Cancer Research UK is calling on political leaders to step up and ensure patients get the level of care that they deserve

People in the UK were treated with chemotherapy ...

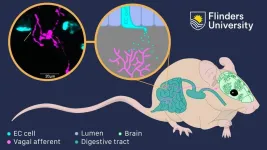

Gut-brain communication turned on its axis

2024-02-27

The mechanisms by which antidepressants and other emotion-focused medications work could be reconsidered due to an important new breakthrough in the understanding of how the gut communicates with the brain.

New research led by Flinders University has uncovered major developments in understanding how the gut communicates with the brain, which could have a profound impact on the make-up and use of medications such as antidepressants.

“The gut-brain axis consists of complex bidirectional neural communication pathway between the brain and the gut, which links emotional and cognitive ...

NSF and DOE establish a Research Coordination Network dedicated to enhancing privacy research

2024-02-27

In response to the rapidly evolving landscape of data collection and analysis driven by advances in artificial intelligence, the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) have established a Research Coordination Network (RCN) dedicated to advancing privacy research and the development, deployment and scaling of privacy enhancing technologies (PETs). Fulfilling a mandate from the "Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence," the initiative advances the recommendations in the National Strategy to Advance ...