(Press-News.org) Of the 38 million Americans who have diabetes at least 90% have Type 2, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Type 2 diabetes occurs over time and is characterized by a loss of the cells in the pancreas that make the hormone insulin, which helps the body manage sugar.

These cells make another protein, called islet amyloid polypeptide or IAPP, which has been found clumped together in many Type 2 diabetes patients. The formation of IAPP clusters is comparable to how a protein in the brains of Alzheimer's disease patients sticks together to eventually form the signature plaques associated with that disease.

Researchers at the University of Washington have demonstrated more similarities between IAPP clusters and those in Alzheimer's. The team previously showed that a synthetic peptide can block the formation of small, toxic Alzheimer's protein clusters. Now, in a recently published paper in Protein Science, the researchers used a similar peptide to block the formation of IAPP clusters.

UW News asked co-senior author Valerie Daggett, a UW professor of bioengineering and faculty member in the UW Molecular Engineering & Sciences Institute, for details about protein aggregation and how these synthetic peptides work.

Alzheimer's and Type 2 diabetes are part of a family of amyloid diseases that are characterized by having proteins that cluster together. What's happening?

Valerie Daggett: There are over 50 of these amyloid diseases, and they start out with their respective proteins in their biologically active, good form. But then the proteins start changing structure and globbing together. These aggregates can be different sizes. They can have different underlying structures and different effects on the cells around them.

Early in the process there are smaller clusters, which are toxic, and they set off all kinds of problems. This leads to a very complicated disease because lots of other things go awry in response to these toxic clusters. Over time, these clusters combine to form non-toxic structures: longer strands and finally large deposits, such as the Alzheimer's plaques.

Many people know that protein aggregation plays a role in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease. Can you describe what's happening here?

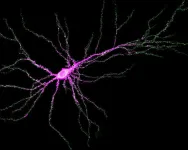

VD: In the case of Alzheimer's, these small, toxic protein clusters are running around the brain attacking neurons and then over time there's enough damage that we start to see symptoms. By the time these clusters have combined to form the non-toxic plaques, there's already been a lot of damage. It becomes similar to trying to treat stage 4 cancer. That's why we want to get in early.

What's happening with Type 2 diabetes?

VD: It's similar, except it’s happening in the pancreas instead of the brain. In healthy people, cells in the pancreas, called beta cells, secrete IAPP along with insulin. The normal, active form of IAPP helps with metabolism maintenance. But when IAPP changes shape, it starts to form these toxic clusters and then it starts attacking the beta cells. And these clusters are equal-opportunity toxins. We, and many others, have shown that you can put them on different cell types and they will kill the cells.

In this paper, you show that the IAPP clusters go through an "alpha sheet" phase. What does this mean and why is it significant?

VD: We've been looking at these amyloid systems for a long time and we started seeing this weird protein structure. It's like every other one of the protein building blocks, called amino acids, has had this crankshaft motion on it. Half of them are rotated the wrong way.

At first we thought: "That's got to be an artifact. Nobody discovers a new structure." But we've since shown that this "alpha sheet" structure is real. And proteins in all the amyloid systems we've looked at — 14 now including Type 2 diabetes — form these alpha sheet structures when they're in these small, toxic clusters. No one had seen that for IAPP before this paper.

Also in this paper, you showed that a synthetic peptide was able to bind and neutralize the toxic IAPP clusters and keep beta cells alive. What's special about this peptide and how does it work?

VD: Previously, we designed synthetic peptides to bind to the toxic protein clusters in Alzheimer's disease. The idea here is for these peptides to take these clusters out of commission before they can wreak havoc on the cells. The peptide we made also forms an alpha sheet structure, but it is not toxic to the cells. It binds really tightly to the clusters, and we're currently studying what happens to the clusters after it binds.

In this paper, we showed that our synthetic peptides also work against the toxic IAPP clusters, which means this could be a potential therapeutic in the future.

Type 2 diabetes is the most prevalent amyloid disease — it affects half a billion people worldwide. A lot of people associate Type 2 diabetes treatment with changing lifestyle measures, but that doesn't work for everyone. A drug that could help minimize the damage IAPP does to the pancreas could be really helpful.

This paper had two lead authors: Cheng-Chieh Hsu, who completed this research as a UW doctoral student of molecular engineering and is now at Columbia University, and Andrew T. Templin, who completed this research as an acting instructor of medicine in the UW School of Medicine and is now at Indiana University. Additional co-authors on this paper are Tatum Prosswimmer, a UW doctoral student of molecular engineering; Dylan Shea, who completed this research as a UW doctoral student of molecular engineering and is now at Ambit Inc; Jinzheng Li, who completed this research as a UW undergraduate student majoring in biochemistry and is now a student at Pacific Northwest University of Health Sciences; Barbara Brooks-Worrell, who completed this research as a senior research scientist in the Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology and Nutrition in the UW School of Medicine and is now at Tacoma Community College; and Dr. Steven E. Kahn, professor of medicine in the UW School of Medicine.

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the University of Washington Office of Research, the UW Department of Bioengineering, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the American Diabetes Association and a UW Mary Gates Research Scholarship.

For more information, contact Daggett at daggett@uw.edu.

END

Q&A: How a potential treatment for Alzheimer’s disease could also work for Type 2 diabetes

2024-02-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Cyber-physical heating system may protect apple blossoms in orchards

2024-02-29

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Spring frosts can have devastating effects on apple production, and a warming climate may be causing trees to blossom early, making them more susceptible to the damaging effects of extreme cold events. Growers’ attempts to prevent the flowers from freezing by attempting to heat the canopies of their orchards largely have been inefficient.

To deal with the worsening problem, Penn State researchers devised a frost protection cyber-physical system, which makes heating decisions based on real-time temperature and wind-direction data. The system consists of a temperature-sensing device, a propane-fueled heater that ...

NYC ranks safest among big US cities for gun violence, new research from NYU Tandon School of Engineering reveals

2024-02-29

New York City ranks in the top 15 percent safest of more than 800 U.S. cities, according to a pioneering new analysis from researchers at NYU Tandon School of Engineering, suggesting the effectiveness of the city’s efforts to mitigate homicides there.

In a paper published in Nature Cities, a research team explored the role that population size of cities plays on the incidences of gun homicides, gun ownership and licensed gun sellers.

The researchers found that none of these quantities vary linearly with the population size. ...

A landmark study maps the precise orchestration of prenatal development

2024-02-29

In a landmark study, researchers at University of Washington and The Jackson Laboratory have characterized, in exacting detail, the rapid series of events that transform a single fertilized cell into a living, complex being. The work, reported this month in Nature, not only has enabled the team to explore which genes drive the differentiation of hundreds of cell types, but also shows, for the first time, that there are very rapid changes in genetic activity within the hour immediately following birth, underscoring the speed with which newborns must adapt.

“The ...

Unveiling rare diversity: the origin of heritable mutations in trees

2024-02-29

Tropical trees are at the heart of this study. They are essential for climate regulation, maintaining biodiversity and providing crucial resources for many local communities. Understanding how they evolve genetically is therefore of vital importance for preserving biological diversity and finding sustainable solutions for tropical forest adaptation to the environmental pressures they face.

The aim of this study was to identify the mutations accumulated during growth by two specimens of tropical trees sampled in French Guiana, a French overseas department covered to 96% by tropical forest. To do this, the scientists ...

Tandem cycling linked to improved health for those with Parkinson’s, care partners

2024-02-29

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE UNTIL 4 P.M. ET, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 29, 2024

MINNEAPOLIS – Pedaling on a stationary bicycle built for two may improve the health and well-being for both people with Parkinson’s disease and their care partners, according to a small, preliminary study released today, February 29, 2024, that will be presented at the American Academy of Neurology’s 76th Annual Meeting taking place April 13–18, 2024, in person in Denver and online.

“Our study found that a unique cycling program that pairs people with Parkinson’s disease with their care partners can improve ...

Preprints raise possibility of rethinking the peer-review process as they become more widely used and accepted

2024-02-29

Preprints raise possibility of rethinking the peer-review process as they become more widely used and accepted – new article encourages their growing momentum and provides recommendations to empower researchers to provide open and constructive peer review for preprints

#####

In your coverage, please use this URL to provide access to the freely available paper in PLOS Biology: http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3002502

Article Title: Recommendations for accelerating ...

A new channel for touch

2024-02-29

Every hug, every handshake, every dexterous act engages and requires touch perception. Therefore, it is essential to understand the molecular basis of touch. “Until now, we had known that the ion channel – Piezo2 – is required for touch perception, but it was clear that this protein alone cannot explain the entirety of touch sensation,” says Professor Gary Lewin, head of the Molecular Physiology of Somatic Sensation Lab at the Max Delbrück Center.

For over 20 years Lewin has been studying the molecular basis of the sensation ...

Scientists identify new ‘regulatory’ function of learning and memory gene common to all mammalian brain cells

2024-02-29

Johns Hopkins Medicine neuroscientists say they have found a new function for the SYNGAP1 gene, a DNA sequence that controls memory and learning in mammals, including mice and humans.

The finding, published March 1 in Science, may affect the development of therapies designed for children with SYNGAP1 mutations, who have a range of neurodevelopmental disorders marked by intellectual disability, autistic-like behaviors, and epilepsy.

In general, SYNGAP1, as well as other genes, control learning and memory by making proteins that regulate the strength of synapses — the connections between brain ...

Ultraviolet “winds” erode a young star’s protoplanetary disk in Orion Nebula

2024-02-29

Ultraviolet “winds” from nearby massive stars are stripping the gas from a young star’s protoplanetary disk, causing it to rapidly lose mass, according to a new study. It reports the first directly observed evidence of far-ultraviolet (FUV)-driven photoevaporation of a protoplanetary disk. The findings, which use observations from the James Web Space Telescope (JWST), provide new insights into the constraints of gas giant planet formation, including in our own Solar System. Young low-mass stars are often surrounded by relatively short-lived protoplanetary disks of dust and gas, which provide the raw materials from which planets ...

Pelagic fish more impacted by human pressures and protections than benthic species

2024-02-29

Pelagic fish – species that occupy the water column of the open ocean, neither near the bottom nor near the shore – are more impacted by both human pressure and protection than bottom-dwelling benthic species, researchers report. The findings highlight the need for increased marine protection in remote pelagic locations. Body size is a universal biological property that influences a range of ecological processes in marine ecosystems. Measuring body-size-structured variation can be a useful framework for understanding and predicting the impacts of overfishing or the success ...