(Press-News.org) Johns Hopkins Medicine neuroscientists say they have found a new function for the SYNGAP1 gene, a DNA sequence that controls memory and learning in mammals, including mice and humans.

The finding, published March 1 in Science, may affect the development of therapies designed for children with SYNGAP1 mutations, who have a range of neurodevelopmental disorders marked by intellectual disability, autistic-like behaviors, and epilepsy.

In general, SYNGAP1, as well as other genes, control learning and memory by making proteins that regulate the strength of synapses — the connections between brain cells.

Previously, the researchers say, the SYNGAP1 gene was thought to work exclusively by encoding a protein that behaves like an enzyme, regulating chemical reactions that lead to changes in the strength of synapses. Now, the scientists say, their experiments in mice show that protein encoded by the gene may also function more like a so-called scaffolding protein that regulates synaptic plasticity, or how synapses get stronger or weaker over time, independent of its enzyme activity. The SynGAP protein appears to act as a traffic manager, they say, directing where and what brain proteins are at synapses.

With his team, Richard Huganir, Ph.D., Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Neuroscience and Psychological and Brain Sciences and director of the Solomon H. Snyder Department of Neuroscience at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, first isolated the SYNGAP1 gene in 1998.

SynGAP proteins are very abundant at the synapse, says Huganir, and it has long been thought that SynGAP’s main role was to spark enzymatic chemical reactions that regulate synapse strength.

But, working with the SynGAP protein, Huganir and others had begun to see that SynGAP proteins have a strange property when they interact with the major synaptic scaffolding protein, PSD-95. They morph into liquid droplets.

“For an enzymatic protein, that structural transformation is unusual,” says Huganir.

To tease out and understand the purpose of SynGAP’s peculiar liquid transformation, Huganir, neuroscience instructor Yoichi Araki and Huganir’s research team at Johns Hopkins designed experiments in neurons in which they inserted mutations in the so-called GAP domain of the SYNGAP1 gene that would remove the enzymatic function of SynGAP without affecting its structure.

The Johns Hopkins team found that, even without the enzymatic activity, the synapse worked normally, suggesting that the structural property alone is very important for SynGAP function.

The research team next did the same type of genetic engineering in mice to remove the enzymatic function of SynGAP, and found similar results: Synapses behaved normally, with no problems in synaptic plasticity, and the mice had no difficulty in learning and memory behaviors. The research team says this indicates that SynGAP’s structural property was sufficient for normal cognitive behavior.

To understand how SynGAP’s structure regulates synapses, the scientists analyzed synapses more closely to find that SynGAP protein competed with the binding of AMPA receptor/TARP complexes, a bundle of neurotransmitter proteins that strengthens synapses, and the PSD-95 scaffolding protein.

The experiments suggest that, at rest, SynGAP tightly binds to PSD-95, not allowing it to bind to any other proteins in the synapse. However, during synaptic plasticity, learning and memory, SynGAP protein disconnected from PSD-95, left the synapse and allowed neurotransmitter receptor complexes to bind to PSD-95. This made the synapse stronger and increased transmission between brain cells.

“This sequence happens without the catalytic activity typical of SynGAP,” says Huganir. Rather, SynGAP corrals PSD-95 when bound to it, but when SynGAP leaves this synapse, PSD-95 is open to bind to AMPA receptor/TARP complexes.

In children with SynGAP mutations, about half the number of SynGAP proteins are in the synapse. With fewer SynGAP proteins, PSD-95 may bind more with the AMPA receptor/TARP complexes, changing neuronal connections and creating the increased brain cell activity characteristic of epileptic seizures common among children with SynGAP mutations.

Huganir says that both functions of SynGAP — enzymatic and the “traffic management” action of a scaffolding protein — may now be important in finding treatments for SynGAP-related neurodevelopmental disorders. Their research also suggests that targeting just one function of SynGAP alone may not be enough to have a significant impact.

In addition to Araki and Huganir, Johns Hopkins scientists who authored the report on the research are Kacey Rajkovich, Elizabeth Gerber, Timothy Gamache, Richard Johnson, Thanh Hai Tran, Bian Liu, Qianwen Zhu, Ingie Hong and Alfredo Kirkwood.

Funding for the research was provided by the National Institutes of Health (R01MH112151, R01NS036715, T32MH015330) and the SynGAP Research Fund.

Drs. Araki, Johnson, Hong, and Huganir are inventors of technology that was evaluated as part of the research described in this press release. These technologies are under patent and have been reviewed in accordance with Johns Hopkins policies.

DOI: 10.1126/science.adk1291

END

Scientists identify new ‘regulatory’ function of learning and memory gene common to all mammalian brain cells

Findings in mice may steer search for therapies to treat brain developmental disorders in children with SYNGAP1 gene mutations

2024-02-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

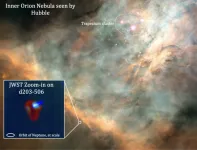

Ultraviolet “winds” erode a young star’s protoplanetary disk in Orion Nebula

2024-02-29

Ultraviolet “winds” from nearby massive stars are stripping the gas from a young star’s protoplanetary disk, causing it to rapidly lose mass, according to a new study. It reports the first directly observed evidence of far-ultraviolet (FUV)-driven photoevaporation of a protoplanetary disk. The findings, which use observations from the James Web Space Telescope (JWST), provide new insights into the constraints of gas giant planet formation, including in our own Solar System. Young low-mass stars are often surrounded by relatively short-lived protoplanetary disks of dust and gas, which provide the raw materials from which planets ...

Pelagic fish more impacted by human pressures and protections than benthic species

2024-02-29

Pelagic fish – species that occupy the water column of the open ocean, neither near the bottom nor near the shore – are more impacted by both human pressure and protection than bottom-dwelling benthic species, researchers report. The findings highlight the need for increased marine protection in remote pelagic locations. Body size is a universal biological property that influences a range of ecological processes in marine ecosystems. Measuring body-size-structured variation can be a useful framework for understanding and predicting the impacts of overfishing or the success ...

Climate change is altering the seasonal pattern of river flow globally

2024-02-29

Climate change is altering the seasonality of river flow, particularly at high northern latitudes, according to a new study. Patterns in river flow vary with the seasons – a cycle that plays a critical role in floods and droughts, water security, and the health of biodiversity and ecosystems worldwide. Although recent studies have shown that climate change has already altered river flow seasonality (RFS), much of the evidence is limited to local regions or fails to consider the impact of climate change explicitly, independent of other human impacts to river flow. Consequently, the impact of climate warming on RFS isn’t ...

Conventional supply-side energy policies overlook benefits of demand-side policy approaches

2024-02-29

Energy security is a top priority across all levels of society because a host of global disruptions threaten energy systems and the critical functions they support. Most often, policymakers rely on policies and measurement indicators focused on energy supply to enhance energy security while ignoring demand-side possibilities. However, in a Policy Forum, Nuno Bento and colleagues argue that energy security is not solely security of supply; this limited focus fails to capture the full spectrum of vulnerability to energy crises. “Energy security is more than security ...

Radiation from massive stars shapes planetary systems

2024-02-29

How do planetary systems such as the Solar System form? To find out, CNRS scientists taking part in an international research team1 studied a stellar nursery, the Orion Nebula, using the James Webb Space Telescope2. By observing a protoplanetary disc named d203-506, they have discovered the key role played by massive stars in the formation of such nascent planetary systems3.

These stars, which are around 10 times more massive, and more importantly 100,000 times more luminous than the Sun, expose any planets forming in such systems nearby to very intense ultraviolet radiation. Depending on the mass of the star at the centre of the planetary system, this radiation can either help planets to ...

Climate change disrupts seasonal flow of rivers

2024-02-29

Climate change is disrupting the seasonal flow of rivers in the far northern latitudes of America, Russia and Europe and is posing a threat to water security and ecosystems, according to research published today.

A team of scientists led by the University of Leeds analysed historical data from river gauging stations across the globe and found that 21% of them showed significant alterations in the seasonal rise and fall in water levels.

The study used data-based reconstructions and state-of-the-art simulations to show that river flow is now far less likely to vary with the seasons in latitudes ...

Researchers reveal mechanism of how the brain forms a map of the environment

2024-02-29

When you walk into your kitchen in the morning, you easily orient yourself. To make coffee, you approach a specific location. Maybe you step into the pantry to grab a quick breakfast and then head to your car to drive to your workplace.

How these apparently simple tasks happen is of major interest to neuroscientists at Baylor College of Medicine, Stanford University and collaborating institutions. Their work, published in the journal Science, has significantly improved our understanding of how this occurs by revealing a mechanism at the brain cell level that mediates how an animal moves about in the environment.

“It’s been known that animals and people can find their ...

Improving energy security with policies focused on demand-side solutions

2024-02-29

Governments typically rely on policies focused on energy supply to enhance energy security, ignoring demand-side options. Current indicators and indexes that measure energy security focus mostly on energy supply. This aligns with the International Energy Agency’s view, which defines energy security only in terms of security of supply. However, this approach does not fully capture the extent of vulnerability for states, businesses, and individuals during an energy crisis.

“Energy security assessments also need to reflect how vulnerable countries, firms, and households are to energy ...

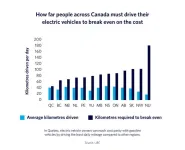

Driving an electric car is cheaper in some parts of Canada than others

2024-02-29

Electric vehicles are a critical part of Canada’s climate strategy, but a new University of British Columbia study highlights how it’s cheaper in some regions than others to drive electric—making it more challenging for certain households to make the switch.

Location, location, location

The researchers analyzed how far people need to drive their electric car to break even on the cost, factoring in the impacts of tax rebates and tax rates, charging costs, typical distance households travel in a region, and electricity ...

Emergency atmospheric geoengineering wouldn’t save the oceans

2024-02-29

WASHINGTON — Climate change is heating the oceans, altering currents and circulation patterns responsible for regulating climate on a global scale. If temperatures dropped, some of that damage could theoretically be undone. But employing “emergency” atmospheric geoengineering later this century in the face of continuous high carbon emissions would not be able to reverse changes to ocean currents, a new study finds. This would critically curtail the intervention’s potential effectiveness ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

[Press-News.org] Scientists identify new ‘regulatory’ function of learning and memory gene common to all mammalian brain cellsFindings in mice may steer search for therapies to treat brain developmental disorders in children with SYNGAP1 gene mutations