(Press-News.org) A protein that appears in postsynaptic protein agglomerations has been found to be crucial to their formation. The Kobe University discovery identifies a new key player for synaptic function and sheds first light on its hitherto uncharacterized cellular role and evolution.

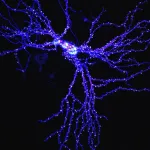

What happens at the synapse, the connection between two neurons, is a key factor in brain function. The transmission of the signal from the presynaptic to the postsynaptic neuron is mediated by proteins and their imbalance can lead to neuropsychiatric conditions such as severe depression, autism, or alcohol dependence. However, due to the vast diversity of proteins present at this junction, many have not yet been studied and often it is not even clear whether those previously found actually belong there or whether they are just impurities resulting from the analysis process. A particularly conspicuous structure directly underneath the postsynaptic membrane is the so-called “postsynaptic density,” an agglomeration of possibly thousands of different proteins.

To shed some light on the postsynaptic density, Kobe University neurophysiologist TAKUMI Toru and his group first compared 35 datasets of previous studies on the phenomenon to find out which uncharacterized proteins appear consistently. KAIZUKA Takeshi, the first author of the paper, explains, “We established an analytical pipeline to unify and align protein structures in different datasets. This resulted in the identification of a poorly characterized synaptic protein that has been detected in more than 20 of these datasets.” This suggested that the protein, which goes by the label FAM81A, is probably relevant to the function of the whole structure, so the team analyzed its interactions with other proteins, its distribution in and around neurons and its effect on neuron shape and function, the mechanism of its function, and its evolution. In short, they gave this protein a full first characterization.

Takumi summarizes their results, now published in the journal PLoS Biology, “The important finding is that FAM81A interacts with at least three major postsynaptic proteins and modulates their condensation. This suggests that FAM81A is a major regulatory factor in the postsynaptic density.” The group could confirm that FAM81A facilitates the condensation of key proteins into a membrane-less organelle through liquid-liquid phase separation, a process in which strongly interacting molecules exclude elements of the surrounding medium, and that the absence of the protein leads to a significant decrease of activity in cultured neurons.

Humans have two related copies of the gene, FAM81A and FAM81B. However, while FAM81A is expressed in the brain, FAM81B is expressed only in the testes. Furthermore, birds and reptiles also have two copies of the gene, but amphibians, fish and invertebrates have only one, and its expression is not localized to one tissue. “Interestingly, it seems that the evolutionary conservation of FAM81A function in the synapse is limited compared to other synaptic molecules, as the FAM81A homolog in fish is not detected in the synapse. This suggests that FAM81A could be a key protein in understanding the cognitive functions of higher vertebrate brains,” says Kaizuka.

But their work was only the first step. To really understand the role of the protein, it is necessary to study its function in the complex environment of the brain. The Kobe University research team thus wants to create mouse models that lack the gene for FAM81A and study what this means both for the function of the synapses and the behavior of the organism.

This research was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grant JP16H06463, JP18K14830, JP22H04981, JP23H04233), the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JPMJMS2299), and the Takeda Science Foundation. It was conducted in collaboration with researchers from the University of Edinburgh, Kyoto University and the University of Sheffield.

Kobe University is a national university with roots dating back to the Kobe Commercial School founded in 1902. It is now one of Japan’s leading comprehensive research universities with nearly 16,000 students and nearly 1,700 faculty in 10 faculties and schools and 15 graduate schools. Combining the social and natural sciences to cultivate leaders with an interdisciplinary perspective, Kobe University creates knowledge and fosters innovation to address society’s challenges.

END

Often seen, never studied: First characterization of a key postsynaptic protein

2024-03-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How does a virus hijack insect sperm to control disease vectors and pests?

2024-03-07

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — A widespread bacteria called Wolbachia and a virus that it carries can cause sterility in male insects by hijacking their sperm, preventing them from fertilizing eggs of females that do not have the same combination of bacteria and virus. A new study led by microbiome researchers at Penn State has uncovered how this microbial combination manipulates sperm, which could lead to refined techniques to control populations of agricultural pests and insects that carry diseases like Zika and dengue to humans.

The study is published in the March 8 issue of the journal Science.

“Wolbachia is the most widespread bacteria in ...

How the brain coordinates speaking and breathing

2024-03-07

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- MIT researchers have discovered a brain circuit that drives vocalization and ensures that you talk only when you breathe out, and stop talking when you breathe in.

The newly discovered circuit controls two actions that are required for vocalization: narrowing of the larynx and exhaling air from the lungs. The researchers also found that this vocalization circuit is under the command of a brainstem region that regulates the breathing rhythm, which ensures that breathing remains dominant over speech.

“When you need to breathe in, you have to stop vocalization. We found that the neurons that control vocalization ...

Shape-shifting ultrasound stickers detect post-surgical complications

2024-03-07

EVANSTON, Ill. — Researchers led by Northwestern University and Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have developed a new, first-of-its-kind sticker that enables clinicians to monitor the health of patients’ organs and deep tissues with a simple ultrasound device.

When attached to an organ, the soft, tiny sticker changes in shape in response to the body’s changing pH levels, which can serve as an early warning sign for post-surgery complications such as anastomotic leaks. Clinicians then ...

The Malaria parasite generates genetic diversity using an evolutionary ‘copy-paste’ tactic

2024-03-07

By dissecting the genetic diversity of the most deadly human malaria parasite – Plasmodium falciparum – researchers at EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) have identified a mechanism of ‘copy-paste’ genetics that increases the genetic diversity of the parasite at accelerated time scales. This helps solve a long-standing mystery regarding why the parasite displays hotspots of genetic diversity in an otherwise unremarkable genetic landscape.

Malaria is most commonly transmitted through the bites of female Anopheles mosquitoes infected with P. falciparum. The latest world malaria report ...

Loss of nature costs more than previously estimated

2024-03-07

Researchers propose that governments apply a new method for calculating the benefits that arise from conserving biodiversity and nature for future generations.

The method can be used by governments in cost-benefit analyses for public infrastructure projects, in which the loss of animal and plant species and ‘ecosystem services’ – such as filtering air or water, pollinating crops or the recreational value of a space – are converted into a current monetary value.

This process is designed to make biodiversity loss and the benefits of nature conservation more visible in political decision-making.

However, the international research team ...

Lack of functional eyes does not affect biological clock in zebrafish

2024-03-07

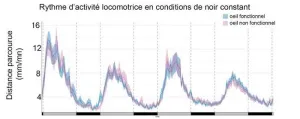

Functional eyes are not required for a working circadian clock in zebrafish, as a research team1 including CNRS scientists has now shown.

Though it is understood that the eye plays a key role in mammalian adaptation to day-night cycles, the circadian clock is most often studied in nocturnal vertebrates such as mice. The zebrafish, in contrast, is a diurnal vertebrate. Through observation of various zebrafish larvae lacking functional eyes,2 the team of scientists has demonstrated that the latter are not needed to establish circadian rhythms that remain synchronized with light-dark ...

The who's who of bacteria: A reliable way to define species and strains

2024-03-07

What’s in a name? A lot, actually.

For the scientific community, names and labels help organize the world’s organisms so they can be identified, studied, and regulated. But for bacteria, there has never been a reliable method to cohesively organize them into species and strains. It’s a problem, because bacteria are one of the most prevalent life forms, making up roughly 75% of all living species on Earth.

An international research team sought to overcome this challenge, which has long plagued scientists who study bacteria. Kostas Konstantinidis, Richard ...

Forbes ranks the University of Colorado Denver | Anschutz Medical campus among America’s best employers

2024-03-07

The University of Colorado Denver | Anschutz Medical Campus is listed as one of Forbes America’s Best Large Employers for 2024.

The 2024 list of “America’s Best Employers” was conducted by Forbes and market research firm Statista, the world-leading statistics portal and industry ranking provider.

“This ranking is meaningful to our organization because the people who work at CU Anschutz drive our success as a leading academic medical campus by providing unparalleled patient care services, being a premier national leader in research and innovation, and fostering a supportive learning ...

NJIT professor trains college counselors to help fight antisemitism

2024-03-07

As data from the Anti-Defamation League shows antisemitism growing on college campuses in recent years and spiking after the Hamas-Israel conflict, a New Jersey Institute of Technology researcher is doing her part to combat the trend by developing a training model that will help prepare mental health professionals who work with Jewish students.

Modern students are hearing people chant slogans without understanding the intentions behind the words, or finding swastikas and other anti-Jewish graffiti on their campuses, but they are not encountering suitably trained counselors and psychologists who understand their ...

For new moms who rent, housing hardship and mental health are linked

2024-03-07

Becoming a parent comes with lots of bills. For new mothers, being able to afford the rent may help stave off postpartum depression.

“Housing unaffordability has serious implications for mental health,” said Katherine Marcal, an assistant professor at the Rutgers School of Social Work and author of a study published in the journal Psychiatry Research. “For mothers who rent their homes, the ability to make monthly payments appears to have a correlation to well-being.”

Housing hardship – missing rent or mortgage payments, moving in with others, being evicted ...