(Press-News.org) In the space of just a few seconds, a person walking down a city block might check their phone, yawn, worry about making rent, and adjust their path to avoid a puddle. The smell from a food cart could suddenly conjure a memory from childhood, or they could notice a rat eating a slice of pizza and store the image as a new memory.

For most people, shifting through behaviors quickly and seamlessly is a mundane part of everyday life.

For neuroscientists, it’s one of the brain’s most remarkable capabilities. That’s because different activities require the brain to use different combinations of its many regions and billions of neurons. How it manages to do this so rapidly has been an open question for decades.

The Study

In a paper published March 8 in Nature Human Behaviour, a team of researchers, led by Joshua Jacobs, associate professor of biomedical engineering at Columbia Engineering, shed new light on this question. By carefully monitoring neural activity of people who were recalling memories or forming new ones, the researchers managed to detect how a newly appreciated type of brainwave — traveling waves — influences the storage and retrieval of memories.

“Broadly, we found that waves tended to move from the back of the brain to the front while patients were putting something into their memory,” said the paper’s co-author Uma R. Mohan, a postdoctoral researcher at NIH and former postdoctoral researcher in the Electrophysiology, Memory, and Navigation Laboratory at Columbia Engineering. “When patients were later searching to recall the same information, those waves moved in the opposite direction, from the front towards the back of the brain,” she said.

In the brains of some of the study’s 93 participants, waves traveled in other directions.

“There was a lot of diversity across patients, so we implemented a framework based on the direction an individual’s oscillations ‘preferred’ to travel,” Mohan said.

The researchers say these findings advance fundamental neuroscience research and point toward diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for memory-related disorders.

“We think the work may lead to new approaches for interfacing with the brain. By measuring the direction that a person’s brain waves move, we may be able to predict their behavior,” Jacobs said.

The Challenge

Brain waves are patterns of electrical oscillations that reflect the state of hundreds or thousands of individual neurons at a particular moment. One major question, which remains unsettled, is whether brain waves drive activity or simply occur as a byproduct of neural activity that was already happening. Researchers who study brain waves have tended to treat them as a stationary phenomenon that occurs in a particular region, noting when oscillations in multiple regions seem synchronized.

In this study, Mohan and her colleagues contribute to a growing understanding of these oscillations differently, as “traveling waves” that spread across the brain’s cortex, the outermost layer that supports higher cognitive processing. Mohan compares the traveling waves to the ripples that would spread outward after a pebble was thrown into a pond.

“We're looking at neural oscillations not as independent stationary things but as things that are constantly and spontaneously moving across the brain in a dynamic way,” Mohan said.

This relatively new way of understanding brain waves is an exciting step in neuroscience because it offers a pathway to explaining how the brain quickly coordinates activity and shares information across multiple regions.

The Experiments and Results

This study drew on data from participants who were being treated for drug-resistant epilepsy at hospitals across the United States. The experiments occurred while the participants had grids or strips of electrodes temporarily implanted on the surface of the brain, beneath the skull, to determine where the patients’ seizures arise. For the researchers, these electrodes offer the chance to perform experiments that wouldn’t otherwise be feasible.

“It’s a rare opportunity to be able to see what's going on directly from the brain while the participants are engaged in different cognitive behaviors,” Mohan said.

During the experiments, researchers recorded the participants’ brain activity while they performed tasks that required memorizing and recalling lists of words or letters.

After the experiments, the researchers analyzed the brain activity from each participant in the context of what they were doing in the memory task and how well they performed.

“I implemented a method to label waves traveling in one direction as basically ‘good for putting something into memory.’ Then we could see how the direction switched over the course of the task,” Mohan said. This method builds on previous research from the Jacobs lab by expanding the mathematical framework used to make sense of the vast quantities of data these experiments produced.

“The waves tended to go in the participant’s encoding direction when that participant was putting something into memory and in the opposite direction right before they recalled the word,” she said. “ Overall, this new work links traveling waves to behavior by demonstrating that traveling waves propagate in different directions across the cortex for separate memory processes.”

The data also showed that participants tended to perform the memory task more accurately when the traveling waves were moving in the appropriate direction for memory storage and recall.

“These findings shed light on the mechanisms that underlie memory processing. More broadly, they help us better understand how the brain supports a wide range of behaviors that involve precisely coordinated interactions between brain regions,” Mohan said.

Potential Impact and Future Directions

As traveling waves are increasingly well understood, they could be the basis for a new class of diagnostic tools that recognize abnormal patterns in brain activity.

There is also significant therapeutic potential.

“If someone’s waves are moving in the wrong direction when they're about to try to remember something, that might put them in a poor memory state,” Mohan explained. “If you could apply stimulation in the right way, you could maybe push those waves to move in a different direction, bringing about a fundamentally different memory state.”

Advances in understanding traveling waves offer significant potential for human-computer interaction.

In terms of both research and application, Mohan notes that memory is just the starting point.

“I am interested in how characteristics of cortical traveling waves change to support a wide range of cognitive functions, including attention and associative memory,” she said.

“The direction of traveling wave propagation may tell us where information is moving across the brain at each moment, showing us how different parts of the brain transfer information during behavior,” Jacobs said.

END

Brain waves travel in one direction when memories are made and the opposite when recalled

2024-03-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Lack of focus doesn’t equal lack of intelligence — it’s proof of an intricate brain

2024-03-08

By Gretchen Schrafft, Science Communications Specialist, Robert J. & Nancy D. Carney Institute for Brain Science

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Imagine a busy restaurant: dishes clattering, music playing, people talking loudly over one another. It’s a wonder that anyone in that kind of environment can focus enough to have a conversation. A new study by researchers at Brown University’s Carney Institute for Brain Science provides some of the most detailed insights yet into the brain mechanisms that help people pay attention amid such distraction, as well as what’s ...

Many type 2 diabetes patients lack potentially life-saving knowledge about their disease

2024-03-08

The body's inability to produce enough insulin or use it effectively often results in type 2 diabetes (T2D), a chronic disease affecting hundreds of millions of people around the globe. Disease management is crucial to avoid negative long-term outcomes, such as limb amputation or heart disease. To counteract adverse consequences, it is crucial that patients have good knowledge about the day-to-day management of the disease.

A team of researchers in Portugal has now assessed how many patients – both insulin-treated and not insulin-treated – have this crucial knowledge about T2D. They published their findings in Frontiers in Public Health.

“Our main motivation ...

Small class sizes not better for pupils’ grades or resilience, says study

2024-03-08

Smaller class sizes in schools are failing to increase the resilience of children from low-income families, according to a study published in the peer-reviewed International Journal of Science Education.

Data on more than 2,700 disadvantaged secondary (high) school students shows that minimizing pupil numbers in classrooms does not lead to better grades. Reducing class sizes could even decrease the odds of children achieving the best results, say the study authors.

The quantity of teachers also does not increase the odds of pupils from the poorest backgrounds achieving academically, despite concerns over staff shortages in schools.

Instead, the researchers ...

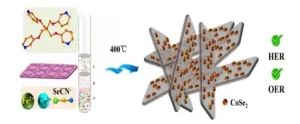

Two-dimensional bimetallic selenium-containing metal-organic frameworks and their calcinated derivatives as electrocatalysts for overall water splitting

2024-03-08

Transition metal selenides have been considered to be a good choice for electrocatalytic water splitting. In addition, Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have been used to make catalysts with good electrocatalytic capabilities. Traditionally, the MOF-derived selenides are produced via the self-sacrificing MOF template methods. However, this strategy is high-energy consuming, and it is difficult to precisely control the structure and component homogeneity of the product during pyrolysis.

A research group of Wang-ting Lu, Fan Yu, and Yun Zheng ...

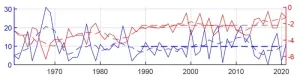

An increase in the number of extreme cold days in North China during 2003–2012

2024-03-08

How extreme weather and climate events change is an intriguing issue in the context of global warming. As IPCC AR6 points out, cold extremes have become less frequent and less severe since the 1950s, mainly driven by human-induced climate change. However, cold extremes could also exhibit robust interdecadal changes at regional scale.

A recent study by researchers from the Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, presents robust interdecadal changes in the number of extreme cold days in winter over North China during 1989–2021, and the findings have been published in Atmospheric and Oceanic Science Letters. ...

Open creativity: Increased creativity due to network relationships

2024-03-08

This paper's objective is to show that the network of frequent relationships that is established between agents in coworking environments, through weak ties, increases the generation of ideas. Thus, the present work argues that collaborative spaces can expand individuals' creativity, as they constitute a social hub for exchanging experiences and visions between individuals from different social and professional backgrounds [Blagoev et al. (2019)]. Through frequent relationships and weak ties, these social connections allow individuals to access different levels of insights and inspirations that make it possible to ...

Reptile roadkill reveals new threat to endangered lizard species

2024-03-08

The chance sighting of a dead snake beside a sandy track in remote Western Australia, and the investigation of its stomach contents, has led Curtin University researchers to record the first known instance of a spotted mulga snake consuming a pygmy spiny-tailed skink, raising concerns for a similar-looking, endangered lizard species.

Lead researcher Dr Holly Bradley from Curtin’s School of Molecular and Life Sciences said the discovery of the partially digested pygmy spiny-tailed skink within the snake had implications for the vulnerable western spiny-tailed skink species.

“Found about 300km east ...

Mutation solves a century-old mystery in meiosis

2024-03-08

Movies such as ‘X-Men,’ ‘Fantastic Four,’ and ‘The Guardians,’ which showcase vibrant mutant heroes, have captivated global audiences. Recently, a high-throughput genetic screening of meiotic crossover rate mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana garnered the interest of the academic community by unraveling a century-old mystery in the life sciences.

A research team, consisting of Professor Kyuha Choi, Dr. Jaeil Kim, and PhD candidate Heejin Kim from the Department ...

How a common food ingredient can take a wrong turn, leading to arthritis

2024-03-08

A University of Colorado Department of Medicine faculty member says she and her colleagues have identified the means in which bacteria in the digestive system can break down tryptophan in the diet into an inflammatory chemical that primes the immune system towards arthritis.

The research was co-authored by Kristine Kuhn, MD, PhD, Scoville Endowed Chair and head of the CU Division of Rheumatology. Several of her division colleagues collaborated on the paper, which was published in February in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Tryptophan is an essential amino acid found in many protein-rich foods, including meats, fish, dairy products, and certain seeds and nuts. It has many uses in the ...

Children with ‘lazy eye’ are at increased risk of serious disease in adulthood

2024-03-08

Adults who had amblyopia (‘lazy eye’) in childhood are more likely to experience hypertension, obesity, and metabolic syndrome in adulthood, as well as an increased risk of heart attack, finds a new study led by UCL researchers.

In publishing the study in eClinicalMedicine, the authors stress that while they have identified a correlation, their research does not show a causal relationship between amblyopia and ill health in adulthood.

The researchers analysed data from more than 126,000 participants aged 40 to 69 years old from the UK Biobank cohort, who had undergone ocular examination.

Participants ...