(Press-News.org) Aging may be less about specific “aging genes” and more about how long a gene is. Many of the changes associated with aging could be occurring due to decreased expression of long genes, say researchers in an opinion piece publishing March 21 in the journal Trends in Genetics. A decline in the expression of long genes with age has been observed in a wide range of animals, from worms to humans, in various human cell and tissue types, and also in individuals with neurodegenerative disease. Mouse experiments show that the phenomenon can be mitigated via known anti-aging factors, including dietary restriction.

“If you ask me, this is the main cause of systemic aging in the whole body,” says co-author and molecular biologist Jan Hoeijmakers of the Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam; the University of Cologne; and Oncode Institute/Princess Maxima Institute, Utrecht.

The authors span four research groups from Spain, the Netherlands, Germany, and the United States, with each group arriving at the same conclusions using different methods.

Aging is associated with changes at the molecular, cellular, and organ level—from altered protein production to sub-optimal cell metabolism to compromised tissue architecture. These changes are thought to originate from DNA damage resulting from cumulative exposure to harmful agents such as UV radiation or reactive oxygen species generated by our own metabolism.

While a lot of research in aging has focused on specific genes that might accelerate or slow aging, investigations of exactly which genes are more susceptible to aging have revealed no clear pattern in terms of gene function. Instead, susceptibility seems to be linked to the genes’ lengths.

“For a long time, the aging field has been focused on genes associated with aging, but our explanation is that it is much more random—it’s a physical phenomenon related to the length of the genes and not to the specific genes involved or the function of those genes,” says co-author Ander Izeta of the Biogipuzkoa Health Research Institute and Donostia University Hospital, Spain.

It essentially comes down to chance; long genes simply have more potential sites that could be damaged. The researchers compare it to a road trip—the longer the trip, the more likely that something will go wrong. And because some cell types tend to express long genes more than others, these cells are more likely to accumulate DNA damage as they age. Cells that don’t (or very rarely) divide also seem to be more susceptible compared to rapidly replicating cells because long-lived cells have more time to accumulate DNA damage and must rely on DNA repair mechanisms to fix them, whereas rapidly dividing cells tend to be short-lived.

Because neural cells are known to express particularly long genes and are also slow or non-dividing, they are especially susceptible to the phenomenon, and the researchers highlight the link between aging and neurodegeneration. Many of the genes involved in preventing protein aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease are exceptionally long, and pediatric cancer patients, who are cured by DNA-damaging chemotherapy, later suffer from premature aging and neurodegeneration.

The authors speculate that damage to long genes could explain most of the features of aging because it is associated with known aging accelerants and because it can be mitigated with known anti-aging therapies, such as dietary restriction (which has been shown to limit DNA damage).

“Many different things that are known to affect aging seem to lead to this length-dependent regulation, for example, different types of irradiation, smoking, alcohol, diet, and oxidative stress,” says co-author Thomas Stoeger of Northwestern University.

However, although the association between the decline in long-gene expression and aging is strong, causative evidence remains to be demonstrated. “Of course, you never know which came first, the egg or the chicken, but we can see a strong relationship between this phenomenon and many of the well-known hallmarks of aging,” says Izeta.

In future studies, the researchers plan to further investigate the phenomenon’s mechanism and evolutionary implications and to explore its relationship with neurodegeneration.

###

This research was supported by the Max Planck Society, the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, the European Research Council, and the NIH.

Trends in Genetics, Soheili-Nezhad et al., “Time is ticking faster for long genes in aging” https://cell.com/trends/genetics/fulltext/S0168-9525(24)00027-1

Trends in Genetics (@TrendsGenetics), published by Cell Press, is a monthly review journal that provides researchers and students with high-quality, novel reviews, commentaries, and discussions and, above all, to foster an appreciation for the advances being made on all fronts of genetic research. Visit http://www.cell.com/trends/genetics. To receive Cell Press media alerts please contact press@cell.com.

END

Scientists have uncovered the fossilized skull of a 270-million-year-old ancient amphibian ancestor in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. In a paper published today, March 21, in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, the team of researchers described the fossil as a new species of proto-amphibian, which they named Kermitops gratus in honor of the iconic Muppet, Kermit the Frog.

According to Calvin So, a doctoral student at the George Washington University and the lead author on the new paper, naming the new creature after the beloved frog character, who was created ...

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Associate Professor and Cancer Center member Tobias Janowitz led a COVID-19 clinical trial with Northwell Health in 2021. When he and Clinical Fellow Hassal Lee reviewed the data, a surprising trend emerged. “The patient roster was very diverse,” Janowitz explains. “We’d made no deliberate effort toward that other than conducting the trial remotely.”

When it comes to cancer trials, many variables impact patient participation. One measurable factor is distance. On average, people are less likely to ...

About The Study: This analysis including 157,000 individuals from two large study cohorts found that among U.S. veterans, higher body mass index (BMI) variability was a significant risk marker associated with adverse cardiovascular events independent of mean BMI across major racial and ethnic groups. Results were consistent in the UK Biobank for the cardiovascular death end point. Further studies should investigate the phenotype of high BMI variability.

Authors: Yan V. Sun, Ph.D., M.S., ...

About The Study: In this early childhood study including 303 children, concussion was associated with more postconcussive symptoms than orthopedic injuries or typical development up to three months after injury. Given the limited verbal and cognitive abilities typical of early childhood, using developmentally appropriate manifestations and behaviors is a valuable way of tracking postconcussive symptoms and could aid in concussion diagnosis in young children.

Authors: Miriam Beauchamp, Ph.D., of the Universite de Montreal, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at ...

The first study of humpback whale entanglements in B.C. aquaculture facilities in PLOS One found eight over 13 years, with the curiosity of young whales a potential contributing factor.

A rare occurrence

Entanglements are one of several threats to humpbacks. The eight occurred from 2008 to 2021 at seven fish farms, with five animals successfully released and three deaths. The entanglements accounted for less than six per cent of all entanglements in B.C. Approximately 7,000 animals return to B.C. waters annually.

Most whales became entangled between the predator and containment nets on fish farms. In five cases, experienced ...

Tokyo, Japan – Drinking milk helps your bones grow big and strong; but what if direct exposure to light could help too? Now, researchers from Japan report that lighting up bone tissue could help treat bone disease.

In a study published last month in Scientific Reports, researchers from Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) have revealed that a treatment approach based on light could help activate bones to repair themselves.

Bones are constantly being remodeled through the action of osteoclasts, which break down bone tissue, and osteoblasts, which create new bone tissue. ...

We are used to computers getting faster and faster, but complicated calculations involving lots of data can take a very long time, even today.

This applies to calculations of chemical reactions, how proteins assume different three-dimensional forms and so-called phase transitions, where one chemical substance transitions from one state to another, such as from solid to liquid form.

These types of results are often very important – for example, in the chemical industry.

Down from one year to ten days

These complicated calculations can take years to perform, and access to the most ...

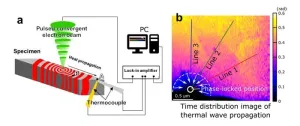

1. A NIMS research team has developed a technique that enables the nanoscale observation of heat propagation paths and behavior within material specimens. This was achieved using a scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) capable of emitting a pulsed electron beam and a nanosized thermocouple—a high-precision temperature measurement device developed by NIMS.

2. Public interest in energy conservation and recycling has grown considerably in recent years. This change has inspired scientists to develop next-generation materials/devices capable of controlling and utilizing heat with a high degree of precision, including thermoelectric devices able to ...

They published their work on Mar. 15th in Energy Material Advances.

"It is highly necessary to design highly conductive and high-performance materials for application in alkaline ion batteries," said paper author Xijun Xu, associate Professor at the College of Chemical Engineering and Light Industry, Guangdong University of Technology.

"In recent years, with the development of large-scale power systems such as electric vehicles, the demand for secondary batteries has gradually shifted towards high power and low cost. Furthermore, in light of the increasing energy and environmental concerns, the exploration of green and renewable ...

They published their work on Mar. 15th in Energy Material Advances.

"The development of cost-effective and high-performance RP anode materials for LIBs/SIBs is imperative," said paper author Hailei Zhao, professor with the Beijing Key Lab of New Energy Materials and Technology, School of Materials Science and Engineering, University of Science and Technology Beijing, "Despite RP shows a great potential, the inherent poor electrical conductivity of RP (~10-14 S cm-1) and significant volume changes during charge/discharge processes (> 300%) compromise its cycling stability."

Zhao explained that the poor electrical conductivity ...