(Press-News.org) For researchers studying the acoustic behavior of whales, distinguishing which animal is vocalizing is like a teacher trying to figure out which student responded first when the entire class is calling out the answer. This is because many of the techniques used to capture audio record a large sample size of sounds. A major example of this is passive acoustic monitoring (PAM), which records audio via a microphone in one location, usually a stationary or moving platform in the ocean. While this method allows researchers to gather acoustic data over a long time period, it is difficult to extrapolate fine-scale information like which animal is producing which call because the incoming audio signals could be from any number of animals within range.

Over the last 20 years, the invention of acoustic tags equipped with movement and audio sensors, which are suctioned harmlessly to the animal being studied, has tremendously improved data collection capabilities. Researchers in Syracuse University’s Bioacoustics and Behavioral Ecology Lab, led by Susan Parks, professor of biology, have been utilizing this technology to study the behavior of humpback whales in the North Atlantic Ocean. In a recent study published in Royal Society Open Science by Julia Zeh, a Ph.D. student in biology, along with other members of Parks’ lab and collaborators from NOAA, the Center for Coastal Studies, and UC Santa Cruz , researchers tagged many whales from the same pod simultaneously to analyze the vocalization of all members in the group. The goal of this research was to uncover new information about whale behavior and communication – insights which are crucial for informing future conservation efforts.

“By simultaneously tagging all whales in a group, we were able to compare how loudly calls were recorded across tags to infer who was calling,” says Zeh. “This in turn lets us look at individual and group-level communication in ways that we couldn’t before.”

The team analyzed nearly 50 hours of synchronous tag data which included 16 tags from seven distinct groups of whales. Sound and movement data were collected from humpback whales in the Gulf of Maine near Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary in the western North Atlantic.

While the function and meaning of specific humpback whale calls remains largely unknown, researchers hypothesize that the calls might be associated with feeding or other social coordination. The team’s simultaneous tagging method allows researchers to analyze acoustic data about individual whales and compare that in the context of the larger group.

“This information can give us insight into how whales coordinate behaviors, how their calls relate to what they’re doing, what types of calls they use and what information they might exchange in group communication,” says Zeh. “Understanding acoustic sequences within and between individuals also gives us insight into the complexity of the humpback whale communication system.”

What’s more, if researchers know who is calling, they can associate vocal behavior with individual age, sex or the behavioral context of the calls. This data can also be used to enhance PAM studies, which are commonly used for species’ presence/absence verification and population counts.

“Having information from tag data about call rates and timing can improve count estimates,” says Zeh. “For example, having 10 calls doesn’t necessarily mean there are 10 whales, but potentially two whales calling back and forth, or one whale producing sequential calls.”

While previous studies have linked caller identity to acoustic tag data, this is the first robust method for studying large baleen whales, like humpback whales. The team's efforts to enhance caller identification through simultaneous tagging provides a new resource for researchers to better understand animal behavior and advance wildlife conservation efforts.

The team’s work was supported by the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, the National Oceanographic Partnership Program, the National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Program, the Office of Naval Research, the ACCURATE Project, the Cetacean Caller-ID project and the U.S. Navy Living Marine Resources Program.

END

Caller ID of the sea

Syracuse University biologists use a novel method of simultaneous acoustic tagging to gain insights into the link between whale communication and behavior

2024-03-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

SwRI develops more effective particle conversion surfaces for space instruments

2024-03-25

SAN ANTONIO — March 25, 2024 —Southwest Research Institute is investing internal funding to develop more effective conversion surfaces to allow future spacecraft instruments to collect and analyze low-energy particles. Conversion surfaces are ultra-smooth, ultra-thin surfaces covering a silicon wafer that convert neutral atoms into ions to more effectively detect particles from outer space.

Changing the charge of particles simplifies and enhances detection and analysis capabilities. Dr. Jianliang Lin of the Institute’s Mechanical Engineering Division and Dr. Justyna Sokół of SwRI’s Space Science Division lead the multidisciplinary project. The project builds ...

Novel quantum algorithm for high-quality solutions to combinatorial optimization problems

2024-03-25

Combinatorial optimization problems (COPs) have applications in many different fields such as logistics, supply chain management, machine learning, material design and drug discovery, among others, for finding the optimal solution to complex problems. These problems are usually very computationally intensive using classical computers and thus solving COPs using quantum computers has attracted significant attention from both academia and industry.

Quantum computers take advantage of the quantum property of superposition, using specialized qubits, that can exist in an infinite yet contained number of states of 0 or 1 or any combination of the two, to quickly ...

Persian plateau unveiled as crucial hub for early human migration out of Africa

2024-03-25

A new study combining genetic, palaeoecological, and archaeological evidence has unveiled the Persian Plateau as a pivotal geographic location serving as a hub for Homo sapiens during the early stages of their migration out of Africa.

This revelation sheds new light on the complex journey of human populations, challenging previous understandings of our species' expansion into Eurasia.

The study, published in Nature Communications, highlights a crucial period between approximately 70,000 to 45,000 years ago when human populations did not uniformly spread across Eurasia, ...

Honey bees at risk for colony collapse from longer, warmer fall seasons

2024-03-25

PULLMAN, Wash. – The famous work ethic of honey bees might spell disaster for these busy crop pollinators as the climate warms, new research indicates.

Flying shortens the lives of bees, and worker honey bees will fly to find flowers whenever the weather is right, regardless of how much honey is already in the hive. Using climate and bee population models, researchers found that increasingly long autumns with good flying weather for bees raises the likelihood of colony collapse in the spring.

The study, published in Scientific Reports, focused on the Pacific Northwest but holds implications for hives across the U.S. The researchers ...

20,000 years of shared history on the Persian plateau

2024-03-25

All present day non African human populations are the result of subdivisions that took place after their ancestors left Africa at least 60.000 years ago. How long did it take for these separations to take place? Almost 20.000 years, during which they were all part of a single population. Where did they live for all this time? We don’t know, yet.

This is a conversation that could have taken place one year ago, now it is possible to give clearer answers to these questions thanks to the study recently published in Nature Communications (1) led by the researchers from the University ...

New UM study reveals unintended consequences of fire suppression

2024-03-25

MISSOULA – The escalation of extreme wildfires globally has prompted a critical examination of wildfire management strategies. A new study from the University of Montana reveals how fire suppression ensures that wildfires will burn under extreme conditions at high severity, exacerbating the impacts of climate change and fuel accumulation.

The study used computer simulations to show that attempting to suppress all wildfires results in fires burning with more severe ecological impacts, with accelerated increases in burned area beyond those expected from fuel accumulation or climate change.

“Fire suppression has unintended consequences,” said lead author Mark Kreider, a Ph.D. ...

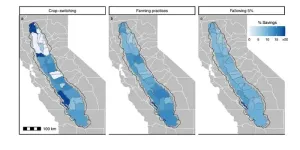

Small changes can yield big savings in agricultural water use

2024-03-25

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) — While Hollywood and Silicon Valley love the limelight, California is an agricultural powerhouse, too. Agricultural products sold in the Golden State totaled $59 billion in 2022. But rising temperatures, declining precipitation and decades of over pumping may require drastic changes to farming. Legislation to address the problem could even see fields taken out of cultivation.

Fortunately, a study out of UC Santa Barbara suggests less extreme measures could help address California’s water issues. Researchers combined remote sensing, big data and machine ...

Humans pass more viruses to other animals than we catch from them

2024-03-25

Humans pass on more viruses to domestic and wild animals than we catch from them, according to a major new analysis of viral genomes by UCL researchers.

For the new paper published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, the team analysed all publicly available viral genome sequences, to reconstruct where viruses have jumped from one host to infect another vertebrate species.

Most emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases are caused by viruses circulating in animals. When these viruses cross over from animals into humans, a process known as zoonosis, they can cause disease outbreaks, epidemics and pandemics such as Ebola, flu or Covid-19. Given the enormous impact ...

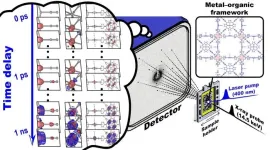

Filming ultrafast molecular motions in single crystal

2024-03-25

Understanding the behavior of matter is crucial for advancing scientific fields like biology, chemistry, and materials science. X-ray crystallography has been instrumental in this pursuit, allowing scientists to determine molecular structures with precision. In traditional X-ray crystallography experiments, a single crystal is exposed to X-rays multiple times to obtain diffraction signals. This poses a problem, where the sample has its structure altered or damaged by X-ray exposure.

In recent years, advances in technology have allowed for the development of “time-resolved serial femtosecond crystallography” (TR-SFX). In serial ...

Better phosphorus use can ensure its stocks last more than 500 years and boost global food production - new evidence shows

2024-03-25

More efficient use of phosphorus could see limited stocks of the important fertiliser last more than 500 years and boost global food production to feed growing populations.

But these benefits will only happen if countries are less wasteful with how they use phosphorus, a study published today in Nature Food shows.

Around 30-40 per cent of farm soils have over-applications of phosphorus, with European and North American countries over-applying the most.

The global population is due to hit nearly 10 billion by 2050 and it is estimated that to feed ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Tools to glimpse how “helicity” impacts matter and light

Smartphone app can help men last longer in bed

Longest recorded journey of a juvenile fisher to find new forest home

Indiana signs landmark education law to advance data science in schools

A new RNA therapy could help the heart repair itself

The dehumanization effect: New PSU research examines how abusive supervision impacts employee agency and burnout

New gel-based system allows bacteria to act as bioelectrical sensors

The power of photonics

From pioneer to leader: Alex Zhavoronkov chairs precision aging discussion and presents Luminary Award to OpenAI president at PMWC 2026

Bursting cancer-seeking microbubbles to deliver deadly drugs

In a South Carolina swamp, researchers uncover secrets of firefly synchrony

American Meteorological Society and partners issue statement on public availability of scientific evidence on climate change

How far will seniors go for a doctor visit? Often much farther than expected

Selfish sperm hijack genetic gatekeeper to kill healthy rivals

Excessive smartphone use associated with symptoms of eating disorder and body dissatisfaction in young people

‘Just-shoring’ puts justice at the center of critical minerals policy

A new method produces CAR-T cells to keep fighting disease longer

Scientists confirm existence of molecule long believed to occur in oxidation

The ghosts we see

ACC/AHA issue updated guideline for managing lipids, cholesterol

Targeting two flu proteins sharply reduces airborne spread

Heavy water expands energy potential of carbon nanotube yarns

AMS Science Preview: Mississippi River, ocean carbon storage, gender and floods

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal reports faster robot-assisted brain angiography

[Press-News.org] Caller ID of the seaSyracuse University biologists use a novel method of simultaneous acoustic tagging to gain insights into the link between whale communication and behavior