What Bronze Age teeth say about the evolution of the human diet

2024-03-27

(Press-News.org)

A new paper in Molecular Biology and Evolution, published by Oxford Univeristy Press, uncovers well-preserved microbiomes from two 4,000 year old teeth in a limestone cave in Ireland. These contained bacteria that cause gum disease, as well as the first high quality ancient genome from S. mutans, an oral bacterium that is one of the major causes of tooth decay.

These discoveries allowed the researchers to assess the impact of past dietary changes on the oral microbiome across millennia, including major changes coinciding with the popularization of sugar and industrialization. The teeth, both derived from the same Bronze Age man, also provided a snapshot of oral health in the past, with one tooth showing evidence of microbiome dysbiosis.

Microbial DNA extracted from ancient human teeth can provide information on the evolution of the oral microbiome. How did our ancestors’ mouths differ from our own and why? The excellent preservation of DNA in fossilized dental plaque has made the oral cavity one of the best studied aspects of the ancient human body. However, scientists have retrieved very few full genomes from oral bacteria from prior to the Medieval era. Researchers have limited knowledge about prehistoric bacterial diversity and the relative impact of recent dietary changes compared to ancient ones, such as the spread of farming starting about ten thousand years ago.

S. mutans is the primary cause of dental cavities and very common in oral microbiomes. However, it is exceptionally rare in the ancient genomic record. One reason for its rarity could be its acid-producing nature – this acid causes the tooth to decay but also degrades DNA and prevents plaque from mineralizing. The absence of S. mutans DNA in ancient mouths could also reflect less favorable habitats for the species across most of human history. Archaeologists have observed an uptick in dental cavities in skeletal remains following the adoption of cereal agriculture, but cavities become much more common in the Early Modern period, beginning about 1500 AD.

The sampled teeth were among a large assemblage of skeletal remains excavated from a limestone cave at Killuragh, County Limerick, by the late Peter Woodman of University College Cork. While other teeth in the cave showed advanced dental decay there was no evidence of caries on the sampled teeth. Nevertheless, one tooth root yielded an unprecedented quantity of mutans sequences.

“We were very surprised to see such a large abundance of mutans in this 4,000 year old tooth” said Lara Cassidy, an assistant professor at Trinity College Dublin and senior author of the study. “It is a remarkably rare find and suggests this man was at high risk of developing cavities right before his death.”

The cool, dry, and alkaline conditions of the cave may have contributed to the exceptional preservation of S. mutans DNA, but its high abundance also points to dysbiosis. The researchers found that while S. mutans DNA was plentiful, other streptococcal species were virtually absent from the tooth sample. This implies that the natural balance of the oral biofilm had been upset – mutans had outcompeted the other species leading to a pre-disease state.

The study lends support to the “disappearing microbiome” hypothesis, which proposes the microbiomes of our ancestors were more diverse than our own today. Alongside the S. mutans genome, the authors reconstructed two genomes for T. forsythia – a bacteria involved in gum disease – and found them to be highly divergent from one another, implying much higher levels of strain diversity in prehistoric populations.

“The two sampled teeth contained quite divergent strains of T. forsythia” explained Iseult Jackson, a PhD candidate and first author of the study. “These strains from a single ancient mouth were more genetically different from one another than any pair of modern strains in our dataset, despite these modern samples deriving from Europe, Japan, and the USA. This is interesting because a loss of biodiversity can have negative impacts on the oral environment and human health.”

The reconstructed T. forsythia and S. mutans genomes revealed dramatic changes in the oral microenvironment over the last 750 years. In recent centuries, one lineage of T. forsythia has become dominant in global populations. This is the tell-tale sign of a selective episode – where one strain rises rapidly in frequency due to some genetic advantage. The researchers found that post-industrial T. forsythia genomes have acquired many new genes that help the bacteria colonize the oral environment and cause disease.

S. mutans also showed evidence of recent lineage expansions and changes in gene content, which coincide with the popularization of sugar. However, the investigators found that modern S. mutans populations have remained more diverse than T. forsythia, with deep splits in the mutans evolutionary tree pre-dating the Killuragh genome. They believe this is driven by differences in the evolutionary mechanisms that shape genome diversity in these species.

“S. mutans is very adept at swapping genetic material across strains.” said Cassidy “This allows an advantageous innovation to be spread across mutans lineages, rather than one lineage becoming dominant and replacing all others.”

In effect, both these disease-causing bacteria have changed dramatically from the Bronze Age to today, but it appears that very recent cultural transitions, such as the consumption of sugar, have had an inordinate impact.

The paper, “Ancient genomes from Bronze Age remains reveal deep diversity and recent adaptive episodes for human oral pathobionts,” is available (at midnight on March 27th) at https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/molbev/msae017.

Direct correspondence to:

Lara Cassidy

Smurfit Institute of Genetics

Trinity College Dublin

Dublin 2, IRELAND

cassidl4@tcd.ie

To request a copy of the study, please contact:

Daniel Luzer

daniel.luzer@oup.com

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2024-03-27

Blood is a remarkable material: it must remain fluid inside blood vessels, yet clot as quickly as possible outside them, to stop bleeding. The chemical cascade that makes this possible is well understood for vertebrate blood. But hemolymph, the equivalent of blood in insects, has a very different composition, being notably lacking in red blood cells, hemoglobin, and platelets, and having amoeba-like cells called hemocytes instead of white blood cells for immune defense.

Just like blood, hemolymph clots quickly outside the body. How it does so has long remained an enigma. Now, materials scientists have shown in Frontiers in Soft ...

2024-03-27

Many people bothered by skin blemishes might turn to laser treatment. To improve efficacy and reduce complications from such laser treatment, an Osaka Metropolitan University-led research group has developed an index of the threshold energy density, known as fluence, and the dependent wavelength for picosecond lasers.

Picosecond lasers have in recent years been used to remove pigmented lesions. These lasers deliver energy beams in pulses that last for about a trillionth of a second. The lasers target melanosomes, which produce, store, ...

2024-03-27

Researchers at the University of Gothenburg warn that today's hunting quotas of about 3,000 animals pose a risk to the long-term survival of the grey seal in the Baltic Sea. The conclusions of this new study are based on statistics from 20th century seal hunting and predictions of future climate change.

After decades of hard hunting and environmental contamination by toxins such as PCBs, there were only 5,000 grey seals left in the entire Baltic Sea by the 1970s, falling from an initial size of more than 90,000 at the ...

2024-03-27

Australian rock-wallabies are ‘little Napoleons’ when it comes to compensating for small size, packing much more punch into their bite than larger relatives.

Researchers from Flinders University made the discovery while investigating how two dwarf species of rock-wallaby are able to feed themselves on the same kinds of foods as their much larger cousins.

Study leader Dr Rex Mitchell also coined the idea of ‘Little Wallaby Syndrome’ after examining the skulls of dwarf rock-wallabies to discover they can more than compensate for their size.

“We already knew that ...

2024-03-27

Reaching sustainability is one of humanity’s most pressing challenges today—and also one of the hardest. To minimize our impact on the environment and start reverting the damage humanity has already caused, striving to achieve carbon neutrality in as many economic activities as possible is paramount. Unfortunately, the synthesis of many important chemicals still causes high carbon emissions.

Such is the case of acetylene (C2H2), an essential hydrocarbon with a plethora of applications. This highly ...

2024-03-27

In recent years, the world has been experiencing floods and droughts as extreme rainfall events have become more frequent due to climate change. For this reason, securing stable water resources throughout the year has become a national responsibility called 'water security', and 'Aquifer Storage Recovery (ASR)', which stores water in the form of groundwater in the ground when water resources are available and withdraws it when needed, is attracting attention as an effective water resource management technique.

The Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) announced that a team of Dr. Seunghak ...

2024-03-27

Researchers at Trinity College Dublin have recovered remarkably preserved microbiomes from two teeth dating back 4,000 years, found in an Irish limestone cave. Genetic analyses of these microbiomes reveal major changes in the oral microenvironment from the Bronze Age to today. The teeth both belonged to the same male individual and also provided a snapshot of his oral health.

The study, carried out in collaboration with archaeologists from the Atlantic Technological University and University ...

2024-03-27

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Improved understanding of driver mutations of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has led to more biomarker-directed treatment for patients with advanced stages. The expanding number of drugs targeting these driver mutations offers more opportunity to improve patient’s survival benefit.

To date, NSCLCs, especially those with non-squamous histology, are recommended for testing epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene rearrangements, ROS proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase 1 (ROS-1) rearrangements, B-raf proto-oncogene (BRAF) mutations, rearranged during transfection ...

2024-03-27

Rabbits are popular family pets, with around 1.5 million* in the UK and it is important that owners can recognise when their animal is in pain, and know when to seek help to protect their rabbit’s welfare. New research by the University of Bristol Veterinary School has found the majority of rabbit owners could list signs of pain and could mostly identify pain-free rabbits and those in severe pain, but many lacked knowledge of the subtler sign of pain.

The study, published in BMC Veterinary Research today [27 March], provides the first insight into how rabbit owners identify pain and their general ability to apply this knowledge to detect pain ...

2024-03-27

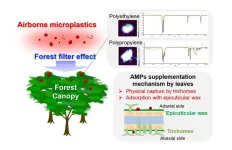

A research group led by Japan Women’s University finds that airborne microplastics adsorb to the epicuticular wax on the surface of forest canopy leaves, and that forests may act as terrestrial sinks for airborne microplastics

Tokyo, Japan – Think of microplastics, and you might think of the ones accumulating in the world’s oceans. However, they are also filling the sky and the air we breathe. Now, it has been discovered that forests might be acting as a sink for these airborne microplastics, offering humanity yet another ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] What Bronze Age teeth say about the evolution of the human diet