(Press-News.org) Repeated exposure to explosive blasts has the potential to cause brain injuries, but there is currently no diagnostic test for these injuries

In a study of 30 active-duty United States SOF personnel, researchers found that increased blast exposure was associated with structural, functional, and neuroimmune changes to the brain and a decline in health-related quality of life

The researchers are now designing a larger study to develop a diagnostic test for repeated blast brain injury

United States (US) Special Operations Forces (SOF) personnel are frequently exposed to explosive blasts during training and combat. However, the effects of repeated blast exposure on the brain health of SOF personnel are unclear, and there is currently no diagnostic test that can detect brain injury caused by the cumulative effects of subconcussive blast exposure.

As a result, SOF personnel may experience cognitive, psychological and physical symptoms for which the cause is never identified, and they may return to training or combat when their brains are vulnerable.

US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) recognizes that the health and well-being of its elite SOF members is a critical element to develop and employ the world's finest warfighters. Because brain health is a key element to fielding a healthy force, USSOCOM willingly participated in this pilot study to help both the US Military and the medical community understand and identify signs related to repeated blast effects. Collectively, USSOCOM hopes that the impact of this study will benefit all US Military members with repeated blast exposure in the future.

To understand the effects of repeated blast exposure on SOF brain health and inform the development of a diagnostic test for repeated blast brain injury, a team at Massachusetts General Hospital, a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, conducted the ReBlast study, a comprehensive, multimodal investigation of 30 active-duty US SOF. The University of South Florida, Institute of Applied Engineering coordinated and managed the study, which was supported by USSOCOM.

In a publication titled “Impact of Repeated Blast Exposure on Active-Duty United States Special Operations Forces,” published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A., the team reports that higher blast exposure was associated with structural, functional, and neuroimmune brain alterations and lower health-related quality of life.

The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) findings converged at a region of the frontal lobe called the rostral anterior cingulate cortex (rACC), which is known to be a widely connected brain network hub that modulates cognition and emotion.

Three lines of evidence – structural MRI, functional MRI, and translocator protein PET – showed an association between cumulative blast exposure and changes in the rACC. Among all the findings, the association between cumulative blast exposure and structural MRI changes in the rACC was the most significant. These results suggest that the rACC may be particularly sensitive to blast waves that penetrate the openings in the skull behind the eyes.

Higher cumulative blast exposure was also associated with decreased health-related quality of life on self-reported questionnaires. However, blast exposure was not associated with changes in cognitive performance, post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, or blood proteomics. No signs of blast-related brain injury were identified by conventional MRI scans.

Higher cumulative blast exposure was also associated with decreased health-related quality of life on self-reported questionnaires. However, blast exposure was not associated with changes in cognitive performance, post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, or blood proteomics. No signs of blast-related brain injury were identified by conventional MRI scans.

Characteristics of Study Participants

SOF study participants represented all branches of the military and included both enlisted personnel and officers. On average, participants were 37 years old and had 17 years of military service. All participants had extensive combat exposure and reported levels of cumulative blast exposure at which individuals are likely to experience cognitive, physical or psychological symptoms. They also reported high levels of blunt impacts to the head, with half the cohort having more blows to the head than they could recall.

These blunt head impacts, as well as age and amount of combat exposure, were accounted for in statistical analyses that tested for associations between blast exposure and a broad spectrum of cognitive, physical symptom, psychological, neuroimaging and blood-based biomarkers.

“A key limitation of the study is that we were unable to measure the many additional exposures that SOF personnel experience during training and combat, such as inhalation of heavy metals, lack of oxygen during high-altitude jumping or deep-sea diving, and acceleration g-forces when flying in aircraft or traveling over waves at high speeds,” explains Brian L. Edlow, MD, principal investigator of the study. “As a result, the associations we observed between cumulative blast exposure and brain network disruption do not prove causation.”

Dr. Edlow is co-director of Mass General Neuroscience, associate director of the Center for Neurotechnology and Neurorecovery (CNTR) at Mass General, an associate professor of Neurology at Harvard Medical School and a Chen Institute MGH Research Scholar 2023-2028.

“Future studies with more comprehensive and objective exposure measurements, larger sample sizes, and a longitudinal design are needed to definitively link blast exposure to the imaging biomarkers that we observed,” adds Natalie Gilmore, PhD, first author of the study and a research fellow in the CNTR.

The researchers are now designing such a longitudinal study with the goal of developing a reliable diagnostic test for repeated blast brain injury. Although no specific blood-based biomarkers for brain injury were detected during the study, the researchers did find higher than expected levels of tau in the blood of study participants, a finding that could help in developing a portable diagnostic test.

“The availability of a reliable diagnostic test could improve Operators’ quality of life by ensuring that they receive timely, targeted medical care for symptoms related to repeated blast brain injury,” explains Yelena G. Bodien, PhD, co-senior author of the paper and an investigator in the CNTR. “A diagnostic test could also be used to inform decisions by Commanders about the combat readiness of individual Operators.”

“Ultimately, the goal of this research is to enhance the combat readiness, career longevity, and quality of life of the United States’ most elite forces,” Edlow says.

“These are American heroes who answered the call to serve after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 and fought the most dangerous missions of the Global War on Terror for two decades. They deserve the best medical care, and while more research is needed, our results suggest that a diagnostic test for repeated blast brain injury is within reach.”

Authorship: In addition to Edlow, Bodien, and Gilmore, Tseng and Maffei were co-first authors.

Disclosures: Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article.

Funding: This study was funded by the U.S. Department of Defense (USSOCOM Contract No. H9240520D0001). Support was also provided by the Navy SEAL Foundation.

Paper cited: Gilmore N*, Tseng CJ*, Maffei C*, et al. Impact of repeated blast exposure on active-duty United States Special Operations Forces. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A. 2024. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2313568121 (*co-first authors)

About Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The Mass General Research Institute conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the nation, with annual research operations of more than $1 billion and comprises more than 9,500 researchers working across more than 30 institutes, centers and departments. MGH is a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system.

About the University of South Florida, Institute of Applied Engineering

The University of South Florida's Institute of Applied Engineering (IAE) represents a beacon of innovation and excellence. Skillfully blending academic prowess with practical application, the IAE addresses some of the nation's most critical challenges. Since its inception, the IAE has emerged as a vital partner to the Department of Defense, NASA, and other federal agencies, managing multimillion-dollar contracts to enhance the capabilities of our nation's defense mechanisms. With expertise spanning Integrated Systems, Software Systems, Intelligent Systems, and beyond, the Institute delivers comprehensive solutions through a synergistic approach that combines the talents of USF's esteemed faculty, a nationwide consortium of over 43 universities, and agile small businesses. The IAE's model of integrating research, development, rapid prototyping, and education is optimized to address the nation’s most complex issues.

About US Special Operations Command

USSOCOM develops, and employs, the world's finest SOF to conduct global special operations and activities as part of the Joint Force, in concert with the U.S. Government Interagency, Allies, and Partners, to support persistent, networked, and distributed combatant command operations and campaigns against state and non-state actors, all to protect and advance U.S. policies and objectives.

END

Study identifies signs of repeated blast-related brain injury in active-duty United States Special Operations Forces

Repeated exposure to explosive blasts has the potential to cause brain injuries, but there is currently no diagnostic test for these injuries.

2024-04-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Mount Sinai scientists discover the cellular functions of a family of proteins integral to inflammatory diseases

2024-04-22

New York, NY (April 22, 2024) – In a scientific breakthrough, Mount Sinai researchers have revealed the biological mechanisms by which a family of proteins known as histone deacetylases (HDACs) activate immune system cells linked to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other inflammatory diseases.

This discovery, reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), could potentially lead to the development of selective HDAC inhibitors designed to treat types of IBD such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

“Our understanding of the specific function of class II HDACs in different cell types has been limited, impeding ...

Spanish scientists identify the key cell type for strategies to prevent atherosclerosis in progeria syndrome

2024-04-22

Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) is an extremely rare genetic disease that affects just 1 in every 20 million people; it is estimated that fewer than 400 children in the world have the disease. HGPS is characterized by accelerated aging, severe atherosclerosis, and premature death at an average age of about 15 years. Although people with HGPS do not normally have conventional cardiovascular risk factors (hypercholesterolemia, obesity, smoking, etc.), most patients die from the complications of atherosclerosis: myocardial ...

A new Spanish study provides the first stratification of the risk of developing dilated cardiomyopathy among symptom-free genetic carriers

2024-04-22

Dilated cardiomyopathy is the most frequent cause of heart failure in young people and is the leading cause of heart transplantation. In this disease, the heart enlarges and reduces its capacity to pump blood. People with dilated cardiomyopathy are at high risk for arrhythmias and sudden death.

In approximately 30%–40% of people with dilated cardiomyopathy, the disease is caused by a genetic mutation. When a genetic cause is identified, the patient’s family members can be studied to determine if they have also inherited the altered gene.

Family members who are carriers of the genetic mutation are at risk for developing the disease in ...

International Lawyer from the University of Warwick calls for fairness in WHO Pandemic Treaty Talks

2024-04-22

As the World Health Organization (WHO) pushes for countries to seal the Pandemic Treaty by May this year, researchers at the University of Warwick and Kings College London stress the need for fair negotiations.

The opinion piece, featured in PLOS Global Public Health journal, is led by Professor Sharifah Sekalala . The team highlights the importance of considering "Time Equity" in these talks, urging caution on setting deadlines and sharing the burden when time is tight.

Since COVID-19 hit, demands for health equity ...

International Society for Autism Research (INSAR) 23rd Annual Meeting to be held in Melbourne, Australia May 15-18, 2024

2024-04-22

The International Society for Autism Research (INSAR) will hold its 2024 Annual Meeting – the organization’s 23rd – from Wednesday, May 15 through Saturday, May 18, 2024, bringing together a global, multidisciplinary group of more than 1,200 autism researchers, clinicians, advocates, self-advocates, and students from 20 countries to exchange the latest scientific learnings and discoveries that are advancing the expanding understanding of autism and its complexities. This year’s ...

Liquid droplets shape how cells respond to change

2024-04-22

Healthy cells respond appropriately to changes in their environment. They do this by sensing what’s happening outside and relaying a command to the precise biomolecule in the precise domain that can carry out the necessary response. When the message gets to the right domain at the right time, your body stays healthy. When it ends up at the wrong place at the wrong time, you can get diseases such as diabetes or cancer.

The routes that messages take inside a cell are called signaling pathways. Cells use only a few signaling pathways to respond simultaneously to hundreds of external signals, so those pathways need to be tightly ...

COS Mason researchers translating research into practice to create climate-ready communities across Virginia

2024-04-22

COS Mason Researchers Translating Research Into Practice To Create Climate-Ready Communities Across Virginia

Four Mason researchers received funding for: “ART: Translating Research into Practice to Create Climate-Ready Communities Across Virginia.”

Leah Nichols, Executive Director, Institute for a Sustainable Earth, Research and Innovation Initiatives; James Kinter, Professor, Climate Dynamics, Atmospheric, Oceanic and Earth Sciences (AOES); Director, Center for Ocean-Land-Atmosphere Studies (COLA); Luis Ortiz, Assistant Professor, AOES; and Celso Ferreira, Associate Professor, Sid and Reva Dewberry Department of Civil, Environmental, and Infrastructure Engineering, are ...

Hao receives funding for NOAA AMSU-A CDR Products Support

2024-04-22

Hao Receives Funding for NOAA AMSU-A CDR Products Support ...

Life goals and their changes drive success

2024-04-22

“Where is my life going?” “Who do I want to be?”

As future-thinkers, adolescents spend significant time contemplating these types of questions about their life goals. A new study from the University of Houston shows that as people grow from teenagers to young adults, they tend to change the importance they place on certain life goals, but one thing is certain: The existence of high prestige and education goals, as well as their positive development, can drive success.

“Adolescents who endorsed higher levels of prestige and education goals tended to have higher educational attainment, income, ...

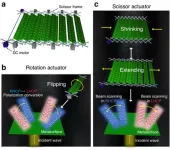

Newmetasurface innovation unlocks precision control in wireless signals

2024-04-22

Researchers have unveiled a technology that propels the field of wireless communication forward. This cutting-edge design, termed a reconfigurable transmissive metasurface, utilizes a synergistic blend of scissor and rotation actuators to independently manage beam scanning and polarization conversion. This introduces an innovative approach to boosting signal strength and efficiency within wireless networks.

Reconfigurable metasurfaces are transforming wireless communication by adjusting electromagnetic (EM) wave characteristics such as amplitude, phase, and polarization. These planar arrays enhance wave control, boosting functionalities ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

[Press-News.org] Study identifies signs of repeated blast-related brain injury in active-duty United States Special Operations ForcesRepeated exposure to explosive blasts has the potential to cause brain injuries, but there is currently no diagnostic test for these injuries.