(Press-News.org) University of Leeds news release

Embargoed until 1900 BST, 9 May 2024

How climate change will affect malaria transmission

A new model for predicting the effects of climate change on malaria transmission in Africa could lead to more targeted interventions to control the disease according to a new study.

Previous methods have used rainfall totals to indicate the presence of surface water suitable for breeding mosquitoes, but the research led by the University of Leeds used several climatic and hydrological models to include real-world processes of evaporation, infiltration and flow through rivers.

This groundbreaking approach has created a more in-depth picture of malaria-friendly conditions on the African continent.

It has also highlighted the role of waterways such as the Zambezi River in the spread of the disease with almost four times the population estimated to live in areas suitable for malaria for up to nine months of the year than was previously thought.

The research entitled “Future malaria environmental suitability in Africa is sensitive to hydrology” was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council and is published today (9 May 2024) in the journal Science.

Dr Mark Smith an Associate Professor in Water Research in the Leeds’ School of Geography and lead author of the study said: “This will give us a more physically realistic estimate of where in Africa is going to become better or worse for malaria.

“And as increasingly detailed estimates of water flows become available, we can use this understanding to direct prioritisation and tailoring of malaria interventions in a more targeted and informed way. This is really useful given the scarce health resources that are often available.”

Malaria is a climate-sensitive vector-borne disease that caused 608,000 deaths among 249 million cases in 2022.

95% of global cases are reported in Africa but reductions in cases there have slowed or even reversed in recent years, attributed in part to a stall in investments in global responses to malaria control.

The researchers predict that the hot and dry conditions brought about by climate change will lead to an overall decrease in areas suitable for malaria transmission from 2025 onwards.

The new hydrology-driven approach also shows that changes in malaria suitability are seen in different places and are more sensitive to future greenhouse gas emissions than previously thought.

For example, projected reductions in malaria suitability across West Africa are more extensive than rainfall-based models suggested, stretching as far east as South Sudan, whereas projected increases in South Africa are now seen to follow watercourses such as the Orange River.

Co-author of the study Professor Chris Thomas from the University of Lincoln said: “The key advancement is that these models factor in that not all water stays where it rains, and this means breeding conditions suitable for malaria mosquitoes too can be more widespread – especially along major river floodplains in the arid, savannah regions typical of many regions in Africa.

“What is surprising in the new modelling is the sensitivity of season length to climate change - this can have dramatic effects on the amount of disease transmitted.”

Simon Gosling, Professor of Climate Risks & Environmental Modelling at the University of Nottingham, co-authored the study and helped to coordinate the water modelling experiments used in the research. He said: “Our study highlights the complex way that surface water flows change the risk of malaria transmission across Africa, made possible thanks to a major research programme conducted by the global hydrological modelling community to compile and make available estimates of climate change impacts on water flows across the planet.

“Although an overall reduction in future risk of malaria might sound like good news, it comes at a cost of reduced water availability and a greater risk of another significant disease, dengue.”

The researchers hope that further advances in their modelling will allow for even finer details of waterbody dynamics which could help to inform national malaria control strategies.

Dr Smith added: “We're getting to the point soon where we use globally available data to not only say where the possible habitats are, but also which species of mosquitoes are likely to breed where, and that would allow people to really target their interventions against these insects.”

Ends

Further information

“Future malaria environmental suitability in Africa is sensitive to hydrology” is published today (9 May 2024) in Science

The DOI is 10.1126/science.adk8755

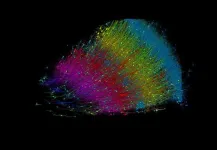

A graphic to illustrate changes in the patterns of transmission can be found here

Caption to read:

Projected changes in the season length of malaria transmission suitability by 2100 under a high-emissions scenario. Red shades show extended season lengths while blue shades show a reduction in season lengths. The intensity of the shading indicates the confidence of estimates.

This work was undertaken with support from the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) award FLOODMAL (NE/P013481/1) (MWS and CJT), and Leeds-York-Hull NERC Doctoral Training Partnership (NE/S007458/1) (EM). The paper is also based upon work undertaken as part of COST Action PROCLIAS, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology), www.cost.eu.

For media enquiries, please contact Kersti Mitchell in the University of Leeds press office via k.mitchell@leeds.co.uk

University of Leeds

The University of Leeds is one of the largest higher education institutions in the UK, with more than 40,000 students from about 140 different countries. We are renowned globally for the quality of our teaching and research.

We are a values-driven university, and we harness our expertise in research and education to help shape a better future for humanity, working through collaboration to tackle inequalities, achieve societal impact and drive change.

The University is a member of the Russell Group of research-intensive universities, and is a major partner in the Alan Turing, Rosalind Franklin and Royce Institutes www.leeds.ac.uk

Follow University of Leeds or tag us in to coverage: Twitter | Facebook | LinkedIn | Instagram

END

How climate change will affect malaria transmission

2024-05-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Presenting a safer, low-cost, and low-energy whole-body magnetic resonance imaging device

2024-05-09

Machine learning enables cheaper and safer low-power magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without sacrificing accuracy, according to a new study. According to the authors, these advances pave the way for affordable, patient-centric, and deep learning-powered ultra-low-field (ULF) MRI scanners, addressing unmet clinical needs in diverse healthcare settings worldwide. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has revolutionized healthcare, offering noninvasive and radiation-free imaging. It holds immense promise for advancing medical diagnoses through artificial intelligence. However, despite its five decades of development, MRI remains largely inaccessible, particularly ...

Climate models predict larger than expected decline in African malaria transmission areas

2024-05-09

Areas at risk for malaria transmission in Africa may decline more than previously expected because of climate change in the 21st century, suggests an ensemble of environmental and hydrologic models. The combined models predicted that the total area of suitable malaria transmission will start to decline in Africa after 2025 through 2100, including in West Africa and as far east as South Sudan. The new study’s approach captures hydrologic features that are typically missed with standard predictive models of malaria transmission, offering a more nuanced view that could inform malaria control efforts in a warming world. Most of the burden of malaria falls on people living ...

Indian ocean temperature anomalies predict global dengue trends

2024-05-09

Sea surface temperature anomalies in the Indian Ocean predict the magnitude of global dengue epidemics, according to a new study. The findings suggest that the climate indicator could enhance the forecasting and planning for outbreak responses. Dengue – a mosquito-borne flavivirus disease – affects nearly half the world’s population. Currently, there are no specific drugs or vaccines for the disease, and outbreaks can have serious public health and economic impacts. As a result, the ability to predict the risk of outbreaks and prepare accordingly is crucial for many regions where ...

Cubic millimeter fragment of human brain reconstructed at nanoscale resolution

2024-05-09

Using more than 1.4 petabytes of electron microscopy (EM) imaging data, researchers have generated a nanoscale-resolution reconstruction of a millimeter-scale fragment of human cerebral cortex, providing an unprecedented view into the structural organization of brain tissue at the supracellular, cellular, and subcellular levels. The human brain is a vastly complex organ and, to date, little is known about its cellular microstructure, including the synaptic and neural circuits it supports. Disruption of these circuits is known to play a role in myriad brain disorders. Yet studying human brain ...

What makes a public health campaign successful?

2024-05-09

The highest performing countries across public health outcomes share many drivers that contribute to their success. That’s the conclusion of a new study published May 9 in the open-access journal PLOS Global Public Health by Dr. Nadia Akseer, an Epidemiologist-Biostatistician at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and co-author of the study and colleagues in the Exemplars in Global Health (EGH) program.

In recent years, the EGH program has begun to identify and study positive outliers when it comes to global health programs around the world, with an aim of uncovering not only which health interventions work, ...

Manganese sprinkled with iridium: a quantum leap in green hydrogen production

2024-05-09

As the world is transitioning from a fossil fuel-based energy economy, many are betting on hydrogen to become the dominant energy currency. But producing “green” hydrogen without using fossil fuels is not yet possible on the scale we need because it requires iridium, a metal that is extremely rare. In a study published May 10 in Science, researchers led by Ryuhei Nakamura at the RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science (CSRS) in Japan report a new method that reduces the amount of iridium needed for the reaction by 95%, without altering the rate of hydrogen production. This breakthrough could revolutionize our ability to produce ecologically ...

Topological Phonos: Where vibrations find their twist

2024-05-09

An international team of researchers has discovered that the quantum particles responsible for the vibrations of materials—which influence their stability and various other properties—can be classified through topology. Phonons, the collective vibrational modes of atoms within a crystal lattice, generate disturbances that propagate like waves through neighboring atoms. These phonons are vital for many properties of solid-state systems, including thermal and electrical conductivity, neutron scattering, and quantum phases like charge density waves and superconductivity.

The spectrum of phonons—essentially ...

A fragment of human brain, mapped

2024-05-09

A cubic millimeter of brain tissue may not sound like much. But considering that tiny square contains 57,000 cells, 230 millimeters of blood vessels, and 150 million synapses, all amounting to 1,400 terabytes of data, Harvard and Google researchers have just accomplished something enormous.

A Harvard team led by Jeff Lichtman, the Jeremy R. Knowles Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology and newly appointed dean of science, has co-created with Google researchers the largest synaptic-resolution, 3D reconstruction of a piece of human brain to date, showing in vivid detail each cell and its web of neural connections in a piece of human ...

Quantum breakthrough sheds light on perplexing high-temperature superconductors

2024-05-09

Superfast levitating trains, long-range lossless power transmission, faster MRI machines — all these fantastical technological advances could be in our grasp if we could just make a material that transmits electricity without resistance — or ‘superconducts’ — at around room temperature.

In a paper published in the May 10 issue of Science, researchers report a breakthrough in our understanding of the origins of superconductivity at relatively high (though still frigid) temperatures. The findings concern a class of superconductors that has puzzled scientists since 1986, called ‘cuprates.’

“There was tremendous excitement when ...

Vilcek Foundation appoints Dr. Jedd Wolchok to Board of Directors

2024-05-09

The Vilcek Foundation has announced the appointment of Dr. Jedd Wolchok to the board of directors, effective May 1, 2024. Wolchok is the Meyer Director of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center and a professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York.

“Jan, Marica, and I are delighted to welcome Jedd to the Vilcek Foundation board,” says Vilcek Foundation President Rick Kinsel. “We look to our board of directors for insight and perspective on our projects and programs: Jedd is not only a leader in immunotherapy and oncology, but an academic and scientific mentor, and a philanthropist in his own right. We are honored and grateful to have him ...