(Press-News.org) FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. — In the first scientific report of its kind, researchers in Arkansas showed that chickens bred for water conservation continued to put on weight despite heat stress that would normally slow growth.

Research by the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station indicates the specially bred line of chickens developed by Sara Orlowski could save growers thousands of gallons of water and thousands of pounds of food each month without sacrificing poultry health. Orlowski is an associate professor of poultry science with the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture.

As global population increases and usable water diminishes due to climate change patterns, scientists with the Division of Agriculture are looking for ways to raise the world’s most popular meat protein using fewer resources.

The study, which was part of a five-year project funded by a $9.95 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, showed a broiler chicken’s physiology could be significantly improved to convert food and water to body weight even with three weeks of heat stress.

Results from the study were published in Physiological Reports, the American Physiological Society’s scientific journal, as an article titled “Effect of heat stress on the hypothalamic expression profile of water homeostasis-associated genes in low- and high-water efficient chicken lines.” The grant was awarded through NIFA's Agriculture and Food Research Initiative.

Sami Dridi, professor of poultry science specializing in avian endocrinology and molecular genetics, was responsible for conducting the experiment and the driving force in writing the paper.

Walter Bottje, professor of poultry science for the experiment station, is the project director for the USDA Sustainable Agriculture Systems multi-institutional grant led by the Center of Excellence for Poultry Science.

Now in its fifth generation of selection, the high water-efficient line has been measured to consume significantly less water than standard broiler lines in use today. From the time they were hatched to one month old, the high water-efficient line drank 1.3 pounds less water, and about 5.7 ounces less feed, which calculates to a 32-point improvement in water conversion and six-point improvement in feed conversion when compared to a random-bred control line.

While it may not seem like a huge difference, modern chicken houses hold on average 20,000 to as many as 50,000 birds. Although chickens consume more as they grow, the difference for that month of growing equates to 7,800 fewer gallons of water and 17,800 pounds less feed to grow 50,000 water-efficient chickens.

In some conditions, the high water-efficient chicken had food conversion ratios that were just as good or better, and their water conversion ratio was about 55 to 65 percent better, according to Dridi.

Bottje said these recent results from the ongoing research are promising, but the group aims to investigate other physiological characteristics of the high water-efficient line, such as meat quality and gut integrity.

Thirst control

The hypothalamus is the part of the brain that controls thirst. One of the study’s findings was that the hypothalamus of water-efficient chickens differed from the other chickens when exposed to heat stress. The investigation revealed potential molecular signatures for water efficiency and heat tolerance in chickens.

The researchers devised a study that induced heat stress for groups of chickens by increasing the ambient temperature to mimic a summer season in Arkansas. The heat-stress cycle began when the birds were 29 days old. The environment was also kept between 30 and 40 percent relative humidity.

Dridi ran a parallel study comparing data on the divergent lines of chickens.

What they found was surprising.

“What the most interesting thing from that study, when it comes to live performance, is that the heat-stressed birds from the high water-efficient line consumed less water than the non-heat stressed birds from the low water-efficient line,” Orlowski said.

Water is critical to raising chickens. They can go several days without food, but only a few hours without water at high temperatures, Dridi said.

Dridi said high humidity, which would be over 70 percent for chickens, also induces similar heat stress because the chickens cool themselves by breathing. Dridi’s studies on poultry house sprinkler systems kept the humidity lower than the industry standard method and used significantly less water than evaporative cooling cells.

“With water sprinkling systems that can save up to 66 percent water usage in a poultry house, the water conservation of poultry could be improved by a magnitude of three- to four-fold by having chickens that consume less water and still retain growth,” Dridi said.

Project development

Dridi said the idea for water-efficient chickens came from looking at the differences in chicken lines bred as far back as the 1950s. Dridi and other researchers wanted to see how much genetic differences there were between jungle fowl and modern breeds.

Before they could breed water-efficient chickens, though, they had to reliably measure the amount of water chickens drank.

Orlowski was a Ph.D. student when her graduate research team developed a novel low-flow water monitoring system in collaboration with Siloam Springs-based companies Alternative Design and Cobb-Vantress Inc., a primary broiler breeder company. The tool was essential to accurately measure water intake for individual birds in real time.

“When we first started this project in 2018, we evaluated one of our broiler lines, a non-selected control population, and we characterized them for water intake,” Orlowski said. “And within that population there was a variability for water intake. From there, we were able to take our most water-efficient families and our least water-efficient families, establish our research populations and continue to select from there.”

A base population of chickens that were not selected for high or low water-efficiency was kept as a control group to compare changes in each generation, Orlowski noted.

Bottje and Dridi said the work done by Orlowski in selecting the divergent lines of chickens was the most important factor of this experiment. Orlowski said water efficiency in the high water-efficient line is continuing to improve with each succeeding generation. She ranks the water efficiency trait as “moderately heritable.”

“There’s no reason that it will not work for all poultry operations, including turkeys, quail and ducks,” Dridi said.

About the researchers

The lead author on the research article was Loujain Aloui of the Higher School of Agriculture of Mograne at the University of Carthage in Zaghouan, Tunisia, while on an internship with the Center of Excellence for Poultry Science and the Division of Agriculture.

Co-authors included Elizabeth S. Green, Travis Tabler, Kentu Lassiter, Bottje, Dridi and Orlowski with the Center of Excellence for Poultry Science at the Division of Agriculture and Kevin Thompson with the Center for Agricultural Data Analytics with the Division of Agriculture.

To learn more about Division of Agriculture research, visit the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station website: https://aaes.uada.edu. Follow on Twitter at @ArkAgResearch. To learn more about the Division of Agriculture, visit https://uada.edu/. Follow us on Twitter at @AgInArk. To learn about extension programs in Arkansas, contact your local Cooperative Extension Service agent or visit www.uaex.uada.edu.

About the Division of Agriculture

The University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture’s mission is to strengthen agriculture, communities, and families by connecting trusted research to the adoption of best practices. Through the Agricultural Experiment Station and the Cooperative Extension Service, the Division of Agriculture conducts research and extension work within the nation’s historic land grant education system.

The Division of Agriculture is one of 20 entities within the University of Arkansas System. It has offices in all 75 counties in Arkansas and faculty on five system campuses.

The University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture offers all its Extension and Research programs and services without regard to race, color, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, national origin, religion, age, disability, marital or veteran status, genetic information, or any other legally protected status, and is an Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer.

END

Researchers uncover what makes some chickens more water efficient than others

High water-efficient consumed less water even under heat stress

2024-05-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Looking inside battery cells

2024-05-14

Lithium-Ion batteries presently are the ubiquitous source of electrical energy in mobile devices, and the key technology for e-mobility and energy storage. Massive interdisciplinary research efforts are underway both to develop practical alternatives that are more sustainable and environmentally friendly, and to develop batteries that are safer, more performing, and longer-lasting – particularly for applications demanding high capacity and very dense energy storage. Understanding degradations and failure mechanisms in detail opens opportunities to better predict and mitigate them.

In the study, a team of researchers led by the CEA, the ILL and the ESRF in collaboration examined Li-ion ...

Gene expression of a tropical starfish fluctuates between the seasons

2024-05-14

Gene expression of a tropical starfish fluctuates between the seasons

#####

In your coverage, please use this URL to provide access to the freely available paper in PLOS Biology: http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3002620

Article Title: Seasonal tissue-specific gene expression in wild crown-of-thorns starfish reveals reproductive and stress-related transcriptional systems

Author Countries: Australia

Funding: This research was supported by a Linkage Project grant (LP170101049) from the Australian Research Council to BMD, ...

150,000+ people died in three decades to 2019 due to heatwaves according to first global mapping of heat-triggered mortality

2024-05-14

A Monash-led study - the first to globally map heatwave-related mortality over a three-decade period from 1990 to 2019 – has found that an additional 153,000+ deaths per warm season were associated with heatwaves, with nearly half of those deaths in Asia.

In comparison to 1850–1990, the global surface temperature has increased by 1.14℃ in 2013–2022 and is expected to increase by another 0.41-3.41℃ by 2081–2100. With the increasing impacts of climate change, heatwaves are increasing not only in frequency but also in severity and magnitude.

The study, published today in PLOS Medicine and led by Monash University’s Professor Yuming Guo, ...

Study tallies heatwave deaths over recent decades

2024-05-14

Between 1990 and 2019, more than 150,000 deaths around the globe were associated with heatwaves each year, according to a new study published May 14th in PLOS Medicine by Yuming Guo of Monash University, Australia, and colleagues.

Heatwaves, periods of extremely high ambient temperature that last for a few days, can impose overwhelming thermal stress on the human body. Studies have previously quantified the effect of individual heatwaves on excess deaths in local areas, but have not compared these statistics around the globe over such ...

Early diagnosis & treatment of peripheral artery disease essential to improve outcomes, reduce amputation risk

2024-05-14

Guideline Highlights:

The new joint guideline from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology provides recommendations to guide clinicians in the treatment of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD) and supports broad implementation of the PAD National Action Plan – an outline of six strategic goals to improve awareness, detection and treatment of PAD nationwide.

The guideline urges clinicians to be aware of the signs and symptoms of PAD in its four clinical presentations (asymptomatic, chronic symptomatic PAD, chronic limb-threatening ...

Innovative USask 'mini-brains' could revolutionize Alzheimer’s treatment

2024-05-14

SASKATOON--Using an innovative new method, a University of Saskatchewan (USask) researcher is building tiny pseudo-organs from stem cells to help diagnose and treat Alzheimer’s.

When Dr. Tyler Wenzel (PhD) first came up with the idea of building a miniature brain from stem cells, he never could have predicted how well his creations would work.

Now, Wenzel’s “mini-brain” could revolutionize the way Alzheimer’s and other brain-related diseases are diagnosed and treated.

“Never in our wildest dreams did we think that our crazy idea would work,” ...

$1 million grant project tackles economic, marketing gaps in US aquaculture

2024-05-14

MEDIA INQUIRES

Laura Muntean

laura.muntean@ag.tamu.edu

601-248-1891

FOR ...

MIT researchers discover the universe’s oldest stars in our own galactic backyard

2024-05-14

MIT researchers, including several undergraduate students, have discovered three of the oldest stars in the universe, and they happen to live in our own galactic neighborhood.

The team spotted the stars in the Milky Way’s “halo” — the cloud of stars that envelopes the entire main galactic disk. Based on the team’s analysis, the three stars formed between 12 and 13 billion years ago, the time when the very first galaxies were taking shape.

The researchers have coined the stars ...

How to ensure biodiversity data are FAIR, linked, open and future-proof? Policy makers and research funders receive expert recommendations from the BiCIKL project

2024-05-14

Within the Biodiversity Community Integrated Knowledge Library (BiCIKL) project, 14 European institutions from ten countries, spent the last three years elaborating on services and high-tech digital tools, in order to improve the findability, accessibility, interoperability and reusability (FAIR-ness) of various types of data about the world’s biodiversity. These types of data include peer-reviewed scientific literature, occurrence records, natural history collections, DNA data and more.

By ensuring all those data are readily available and efficiently interlinked to each other, the project consortium’s intention is to provide better tools to the scientific community, ...

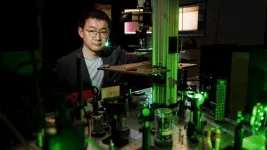

Lessons in chemistry: Guo aims at fundamental understanding of emerging semiconductor material

2024-05-14

Metal halide perovskites have emerged in recent years as a low-cost, highly efficient semiconducting material for solar energy, solid-state lighting and more. Despite their growing use, a fundamental understanding of the origins of their outstanding properties is still lacking. A Husker scientist is aiming to find answers that could lead to the development of new materials and new applications.

Yinsheng Guo, assistant professor of chemistry at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, also wants to transform how physical chemistry is taught to undergraduate and graduate students, who often struggle to understand and apply what ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

RESPIN launches new online course to bridge the gap between science and global environmental policy

[Press-News.org] Researchers uncover what makes some chickens more water efficient than othersHigh water-efficient consumed less water even under heat stress