(Press-News.org) A team of chemists from the University of Vienna, led by Nuno Maulide, has achieved a significant breakthrough in the field of chemical synthesis, developing a novel method for manipulating carbon-hydrogen bonds. This groundbreaking discovery provides new insights into the molecular interactions of positively charged carbon atoms. By selectively targeting a specific C–H bond, they open doors to synthetic pathways that were previously closed – with potential applications in medicine. The study was recently published in the prestigious journal Science.

Living organisms, including humans, owe their complexity primarily to molecules consisting mainly of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen. These building blocks form the basis of countless substances essential for daily life, including medications. When chemists embark on synthesizing a new drug, they manipulate molecules through a series of chemical reactions to create compounds with unique properties and structures.

This process involves breaking and forming bonds between atoms. Some bonds, such as those between carbon and hydrogen (C–H bonds), are particularly strong and require considerable energy to break, while others can be more easily modified. Whereas an organic compound typically contains dozens of C–H bonds, chemists traditionally had to resort to manipulating other, weaker bonds. Such bonds are far less common and often need to be introduced in additional synthetic steps, making such approaches costly – thus, more efficient and sustainable synthetic methods are sought after.

C–H Activation as a New Approach

The concept of C–H activation is a revolutionary approach enabling the direct manipulation of strong C–H bonds. This breakthrough not only enhances the efficiency of synthetic processes but can also often reduce their environmental impact and provide more sustainable paths for drug discovery.

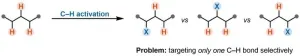

A key challenge is the precise manipulation of a specific C–H bond within a molecule containing many different C–H bonds. This obstacle, known as the "selectivity problem," often hinders the broader application of established C–H activation reactions (Figure 1).

Targeting a Specific C–H Bond

Researchers at the University of Vienna led by Nuno Maulide have now developed a new C–H activation reaction that addresses the selectivity problem and enables the synthesis of complex carbon-based molecules. By selectively targeting a specific C–H bond with remarkable precision, they open doors to synthetic pathways that were previously closed.

The Maulide group focuses on so-called "carbocations" (i.e., molecules containing a positively charged carbon atom) as key intermediates. "Traditionally, carbocations react by eliminating a hydrogen atom adjacent to the carbon atom, forming a carbon-carbon double bond in the product," explains Nuno Maulide (Figure 2A). "Products with double bonds – called alkenes – can be extremely useful. However, sometimes a single bond instead of a double bond is desired," continues the multiple ERC awardee. "We have discovered that in certain cases, reactivity can take a new direction. This leads to a phenomenon called 'remote elimination,' resulting in the formation of a new carbon-carbon single bond – a phenomenon that has not been investigated before," explain Phillip Grant and Milos Vavrík, first authors of the study (Figure 2B).

The researchers demonstrated this new reactivity by synthesizing decalins, a building block for many pharmaceuticals. "Decalins are a class of cyclic carbon-based molecules found in many biologically active compounds. We can now produce these molecules in a much more efficient manner, potentially contributing to the development of new and more effective drugs," concludes Nuno Maulide, the 2019 Austrian Scientist of the Year.

END

Breaking bonds to form bonds: Rethinking the Chemistry of Cations

New chemical reaction with potential applications in medicinal chemistry

2024-05-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New gene delivery vehicle shows promise for human brain gene therapy

2024-05-16

In an important step toward more effective gene therapies for brain diseases, researchers from the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard have engineered a gene-delivery vehicle that uses a human protein to efficiently cross the blood-brain barrier and deliver a disease-relevant gene to the brain in mice expressing the human protein. Because the vehicle binds to a well-studied protein in the blood-brain barrier, the scientists say it has a good chance at working in patients.

Gene therapy could potentially treat a range of severe genetic brain disorders, which currently ...

Finding quantum order in chaos

2024-05-16

If you zoom in on a chemical reaction to the quantum level, you’ll notice that particles behave like waves that can ripple and collide. Scientists have long sought to understand quantum coherence, the ability of particles to maintain phase relationships and exist in multiple states simultaneously; this is akin to all parts of a wave being synchronized. It has been an open question whether quantum coherence can persist through a chemical reaction where bonds dynamically break and form.

Now, for the first time, a team of Harvard scientists has demonstrated the survival of quantum coherence in a chemical reaction involving ultracold molecules. These findings highlight the potential of ...

Study suggests high-frequency electrical ‘noise’ results in congenital night blindness

2024-05-16

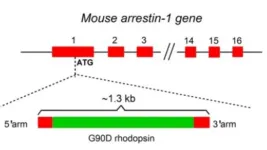

In what they believe is a solution to a 30-year biological mystery, neuroscientists at Johns Hopkins Medicine say they have used genetically engineered mice to address how one mutation in the gene for the light-sensing protein rhodopsin results in congenital stationary night blindness.

The condition, present from birth, causes poor vision in low-light settings.

The findings, published May 14 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, demonstrate that the rhodopsin gene mutation, called ...

TeltoHeart wristband, developed by Lithuanians, receives important medical device certification

2024-05-16

Teltonika’s TeltoHeart, a multifunctional smart wristband system developed in cooperation between Lithuanian industry and universities has been given the CE MDR (Class IIa) medical device certification. This approval confirms that the product meets the comprehensive quality standards for medical devices and opens up new markets worldwide for this innovative product.

"This is an important recognition that we have been working towards since the start of this project in 2020. The CE MDR certification proves that TeltoHeart is a safe ...

Unique brain circuit is linked to Body Mass Index

2024-05-16

· One region is related to olfaction and reward, the other to negative feelings like pain · When the connection between these brain regions is weak, people have higher BMI

· Food may continue to be rewarding, even when these individuals are full

CHICAGO --- Why can some people easily stop eating when they are full and others can’t, which can lead to obesity?

A Northwestern Medicine study has found one reason may be a newly discovered structural connection ...

Noise survey highlights need for new direction at Canadian airports #ASA186

2024-05-16

OTTAWA, Ontario, May 16, 2024 – The COVID-19 pandemic changed life in many ways, including stopping nearly all commercial flights. At the Toronto Pearson International Airport, airplane traffic dropped by 80% in the first few months of lockdown. For a nearby group of researchers, this presented a unique opportunity.

Julia Jovanovic will present the results of a survey conducted on aircraft noise and annoyance during the pandemic era Thursday, May 16, at 11:10 a.m. EDT as part of a joint meeting of the Acoustical Society of America and ...

COSPAR partners with LASP for 1st COSPAR Center of Excellence

2024-05-16

Partnering with LASP was an obvious decision for COSPAR. LASP stands out with its distinguished track record in space science research, having deployed scientific instruments to every planet in our solar system, the Sun and numerous moons. In particular, LASP has been at the forefront of pioneering Cube-Sat missions, consistently achieving remarkable success in gathering scientific data. With seven completed CubeSat missions and nine more in active development or orbit, LASP has demonstrated unparalleled expertise in this field. ...

Building a better sarcasm detector #ASA186

2024-05-16

OTTAWA, Ontario, May 16, 2024 – Oscar Wilde once said that sarcasm was the lowest form of wit, but the highest form of intelligence. Perhaps that is due to how difficult it is to use and understand. Sarcasm is notoriously tricky to convey through text — even in person, it can be easily misinterpreted. The subtle changes in tone that convey sarcasm often confuse computer algorithms as well, limiting virtual assistants and content analysis tools.

Xiyuan Gao, Shekhar Nayak, and Matt Coler of Speech Technology Lab at the University of Groningen, Campus Fryslân developed a multimodal algorithm ...

Natural toxins in food: Many people are not aware of the health risks

2024-05-16

Many people are concerned about residues of chemicals, contaminants or microplastics in their food. However, it is less well known that many foods also contain toxins of completely natural origin. These are often chemical compounds that plants use to ward off predators such as insects or microorganisms. These substances are found in beans and potatoes, for example, and can pose potential health risks. However, according to a recent representative survey by the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR), only just under half of the respondents (47 per cent) were even aware of plant toxic substances. The BfR Consumer Monitor Special on naturally occurring plant toxins ...

Archaeology: Egyptian pyramids built along long-lost Ahramat branch of the Nile

2024-05-16

31 pyramids in Egypt, including the Giza pyramid complex, may originally have been built along a 64-km-long branch of the river Nile which has long since been buried beneath farmland and desert. The findings, reported in a paper in Communications Earth & Environment, could explain why these pyramids are concentrated in what is now a narrow, inhospitable desert strip.

The Egyptian pyramid fields between Giza and Lisht, built over a nearly 1,000-year period starting approximately 4,700 years ago, now sit on the edge of the inhospitable Western Desert, part of the Sahara. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

Gnaw-y by nature: Researchers discover neural circuit that rewards gnawing behavior in rodents

Research alert: How one receptor can help — or hurt — your blood vessels

Lamprey-inspired amphibious suction disc with hybrid adhesion mechanism

A domain generalization method for EEG based on domain-invariant feature and data augmentation

Bionic wearable ECG with multimodal large language models: coherent temporal modeling for early ischemia warning and reperfusion risk stratification

JMIR Publications partners with the University of Turku for unlimited OA publishing

Strange cosmic burst from colliding galaxies shines light on heavy elements

Press program now available for the world's largest physics meeting

New release: Wiley’s Mass Spectra of Designer Drugs 2026 expands coverage of emerging novel psychoactive substances

Exposure to life-limiting heat has soared around the planet

New AI agent could transform how scientists study weather and climate

New study sheds light on protein landscape crucial for plant life

New study finds deep ocean microbes already prepared to tackle climate change

ARLIS partners with industry leaders to improve safety of quantum computers

Modernization can increase differences between cultures

Cannabis intoxication disrupts many types of memory

Heat does not reduce prosociality

Advancing brain–computer interfaces for rehabilitation and assistive technologies

Detecting Alzheimer's with DNA aptamers—new tool for an easy blood test

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal study develops radiomics model to predict secondary decompressive craniectomy

[Press-News.org] Breaking bonds to form bonds: Rethinking the Chemistry of CationsNew chemical reaction with potential applications in medicinal chemistry