(Press-News.org) Researchers discover new pathway to cancer cell suicide

Chemotherapy kills cancer cells. But the way these cells die appears to be different than previously understood. Researchers from the Netherlands Cancer Institute, led by Thijn Brummelkamp, have uncovered a completely new way in which cancer cells die: due to the Schlafen11 gene. "This is a very unexpected finding. Cancer patients have been treated with chemotherapy for almost a century, but this route to cell death has never been observed before. Where and when this occurs in patients will need to be further investigated. This discovery could ultimately have implications for the treatment of cancer patients." They publish their findings in Science.

Many cancer treatments damage cell DNA. After too much irreparable damage, cells can initiate their own death. High school biology teaches us that the protein p53 takes charge of this process. p53 ensures repair of damaged DNA, but initiates cell suicide when the damage becomes too severe. This prevents uncontrolled cell division and cancer formation.

Surprise: unanswered question

That sounds like a foolproof system, but reality is more complex. "In more than half of tumors, p53 no longer functions," says Thijn Brummelkamp. "The key player p53 plays no role there. So why do cancer cells without p53 still die when you damage their DNA with chemotherapy or radiation? To my surprise, that turned out to be an unanswered question."

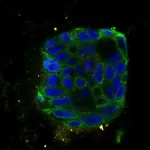

His research group then discovered, together with the group of colleague Reuven Agami, a previously unknown way in which cells die after DNA damage. In the lab, they administered chemotherapy to cells in which they carefully modified the DNA. Thijn: "We were looking for a genetic change that would allow cells to survive chemotherapy. Our group has a lot of experience in selectively disabling genes, which we could perfectly apply here." (see ***)

New key player in cell death

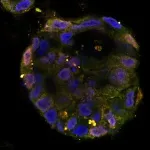

By switching off genes, the research group found a new pathway to cell death headed by the gene Schlafen11 (SLFN11). Principle investigator Nicolaas Boon: "In the event of DNA damage, SLFN11 shuts down the protein factories of cells: the ribosomes. This causes immense stress in these cells, which leads to their death. The new route we discovered completely bypasses p53."

The SLFN11 gene is not unfamiliar in cancer research. It is often inactive in tumors of patients who do not respond to chemotherapy, says Thijn. "We can now explain this link. When cells lack SLFN11 they will not die in this manner in response to DNA damage. The cells will survive and the cancer persist."

Impact on cancer treatment

"This discovery uncovers many new research questions, which is usually the case in fundamental research," says Thijn. "We have demonstrated our discovery in lab-grown cancer cells, but many important questions remain: Where and when does this pathway occur in patients? How does it affect immunotherapy or chemotherapy? Does it affect the side effects of cancer therapy? If this form of cell death also proves to play a significant role in patients, this finding will have implications for cancer treatments. These are important questions to investigate further."

***

Turning off genes, one by one

People have thousands of genes, many of which have functions that are unclear to us. To determine the roles of our genes, researcher Thijn Brummelkamp developed a method using haploid cells. These cells contain only one copy of each gene, unlike the regular cells in our bodies that contain two copies. Handling two copies can be challenging in genetic experiments, because changes (mutations) often occur in just one of them. This makes it difficult to observe the effects of these mutations.

Together with other researchers, Brummelkamp has been unraveling processes that are crucial in disease for years using this versatile method. For example, his group recently discovered that cells can make lipids in a different way than previously known. They uncovered how certain viruses, including the deadly Ebola virus, manage to enter human cells. They delved into cancer cell resistance against specific therapies and identified proteins that act as brakes on the immune system, which is relevant to cancer immunotherapy. Over the last years, his team discovered two enzymes that had remained elusive for four decades, and that turned out to be vital for muscle function and brain development.

This research was financially supported by KWF Dutch Cancer Society, Oncode Institute, and Health Holland.

END

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – Artificial intelligence (AI) has numerous applications in healthcare, from analyzing medical imaging to optimizing the execution of clinical trials, and even facilitating drug discovery.

AlphaFold2, an artificial intelligence system that predicts protein structures, has made it possible for scientists to identify and conjure an almost infinite number of drug candidates for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. However recent studies have sown doubt about the accuracy of AlphaFold2 in modeling ligand binding sites, the areas on proteins where drugs attach and begin signaling ...

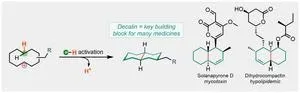

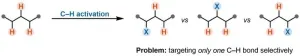

A team of chemists from the University of Vienna, led by Nuno Maulide, has achieved a significant breakthrough in the field of chemical synthesis, developing a novel method for manipulating carbon-hydrogen bonds. This groundbreaking discovery provides new insights into the molecular interactions of positively charged carbon atoms. By selectively targeting a specific C–H bond, they open doors to synthetic pathways that were previously closed – with potential applications in medicine. The study was recently published in the prestigious journal Science.

Living ...

In an important step toward more effective gene therapies for brain diseases, researchers from the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard have engineered a gene-delivery vehicle that uses a human protein to efficiently cross the blood-brain barrier and deliver a disease-relevant gene to the brain in mice expressing the human protein. Because the vehicle binds to a well-studied protein in the blood-brain barrier, the scientists say it has a good chance at working in patients.

Gene therapy could potentially treat a range of severe genetic brain disorders, which currently ...

If you zoom in on a chemical reaction to the quantum level, you’ll notice that particles behave like waves that can ripple and collide. Scientists have long sought to understand quantum coherence, the ability of particles to maintain phase relationships and exist in multiple states simultaneously; this is akin to all parts of a wave being synchronized. It has been an open question whether quantum coherence can persist through a chemical reaction where bonds dynamically break and form.

Now, for the first time, a team of Harvard scientists has demonstrated the survival of quantum coherence in a chemical reaction involving ultracold molecules. These findings highlight the potential of ...

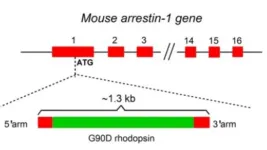

In what they believe is a solution to a 30-year biological mystery, neuroscientists at Johns Hopkins Medicine say they have used genetically engineered mice to address how one mutation in the gene for the light-sensing protein rhodopsin results in congenital stationary night blindness.

The condition, present from birth, causes poor vision in low-light settings.

The findings, published May 14 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, demonstrate that the rhodopsin gene mutation, called ...

Teltonika’s TeltoHeart, a multifunctional smart wristband system developed in cooperation between Lithuanian industry and universities has been given the CE MDR (Class IIa) medical device certification. This approval confirms that the product meets the comprehensive quality standards for medical devices and opens up new markets worldwide for this innovative product.

"This is an important recognition that we have been working towards since the start of this project in 2020. The CE MDR certification proves that TeltoHeart is a safe ...

· One region is related to olfaction and reward, the other to negative feelings like pain · When the connection between these brain regions is weak, people have higher BMI

· Food may continue to be rewarding, even when these individuals are full

CHICAGO --- Why can some people easily stop eating when they are full and others can’t, which can lead to obesity?

A Northwestern Medicine study has found one reason may be a newly discovered structural connection ...

OTTAWA, Ontario, May 16, 2024 – The COVID-19 pandemic changed life in many ways, including stopping nearly all commercial flights. At the Toronto Pearson International Airport, airplane traffic dropped by 80% in the first few months of lockdown. For a nearby group of researchers, this presented a unique opportunity.

Julia Jovanovic will present the results of a survey conducted on aircraft noise and annoyance during the pandemic era Thursday, May 16, at 11:10 a.m. EDT as part of a joint meeting of the Acoustical Society of America and ...

Partnering with LASP was an obvious decision for COSPAR. LASP stands out with its distinguished track record in space science research, having deployed scientific instruments to every planet in our solar system, the Sun and numerous moons. In particular, LASP has been at the forefront of pioneering Cube-Sat missions, consistently achieving remarkable success in gathering scientific data. With seven completed CubeSat missions and nine more in active development or orbit, LASP has demonstrated unparalleled expertise in this field. ...

OTTAWA, Ontario, May 16, 2024 – Oscar Wilde once said that sarcasm was the lowest form of wit, but the highest form of intelligence. Perhaps that is due to how difficult it is to use and understand. Sarcasm is notoriously tricky to convey through text — even in person, it can be easily misinterpreted. The subtle changes in tone that convey sarcasm often confuse computer algorithms as well, limiting virtual assistants and content analysis tools.

Xiyuan Gao, Shekhar Nayak, and Matt Coler of Speech Technology Lab at the University of Groningen, Campus Fryslân developed a multimodal algorithm ...