(Press-News.org) Scientists have discovered that the most widely-used class of antifungals in the world cause pathogens to self-destruct. The University of Exeter-led research could help improve ways to protect food security and human lives.

Fungal diseases account for the loss of up to a quarter of the world’s crops. They also pose a risk to humans and can be fatal for those with weakened immune systems.

Our strongest "weapon" against fungal plant diseases are azole fungicides. These chemical products account for to a quarter of the world agricultural fungicide market, worth more than £3 billion per year. Antifungal azoles are also widely used as a treatment against pathogenic fungi which can be fatal to humans, which adds to their importance in our attempt to control fungal disease.

Azoles target enzymes in the pathogen cell that produce cholesterol-like molecules, named ergosterol. Ergosterol is an important component of cellular bio-membranes. Azoles deplete ergosterol, which results in killing of the pathogen cell. However, despite the importance of azoles, scientists know little about the actual cause of pathogen death.

In a new study published in Nature Communications, University of Exeter scientists have uncovered the cellular mechanism by which azoles kill pathogenic fungi.

Funded by the BBSRC, the team of researchers, led by Professor Gero Steinberg, combined live-cell imaging approaches and molecular genetics to understand why the inhibition of ergosterol synthesis results in cell death in the crop pathogenic fungus Zymoseptoria tritic (Z. tritici). This fungus causes septoria leaf blotch in wheat, a serious disease in temperate climates, estimated to cause more than £250 million per year in costs in the UK alone due to harvest loss and fungicide spraying.

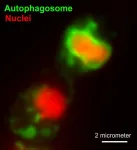

The Exeter team observed living Z. tritici cells, treated them with agricultural azoles and analysed the cellular response. They showed that the previously accepted idea that azoles kill the pathogen cell by causing perforation of the outer cell membrane does not apply. Instead, they found that azole-induced reduction of ergosterol increase the activity of cellular mitochondria, the "powerhouse" of the cell, required to produce the cellular "fuel" that drives all metabolic processes in the pathogen cell. While producing more "fuel" is not harmful in itself, the process leads to the formation of more toxic by-products. These by-products initiate a "suicide" programme in the pathogen cell, named apoptosis. In addition, reduced ergosterol levels also trigger a second "self-destruct" pathway, which causes the cell to "self-eat" its own nuclei and other vital organelles – a process known as macroautophagy (Figure 1). The authors show that both cell death pathways underpin the lethal activity of azoles. They conclude that azoles drive the fungal pathogen into "suicide" by initiating self-destruction.

The authors found the same mechanism of how azoles kill pathogen cells in rice-blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. The disease caused by this fungus kills up to 30 per cent of rice, an essential food crop for more than 3.5 billion people across the world. The team also tested other clinically relevant anti-fungal drugs that target the ergosterol biosynthesis, including Terbinafine, Tolfonate and Fluconazole. All initiated the same responses in the pathogen cell, suggesting that cell suicide is a general consequence of ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors.

Lead author Professor Gero Steinberg, who holds a Chair in Cell Biology and is Director of the Bioimaging Centre at the University of Exeter, said: “Our findings rewrite common understanding of how azoles kill fungal pathogens. We show that azoles trigger cellular "suicide" programmes, which result in the pathogen self-destructing. This cellular reaction occurs after two days of treatment, suggesting that cells reach a "point of no return" after some time of exposure to azoles. Unfortunately, this gives the pathogen time to develop resistance against azoles, which explains why azole resistance is advancing in fungal pathogens, meaning they are more likely to fail to kill the disease in crops and humans.

“Our work sheds light on the activity of our most widely used chemical control agents in crop and human pathogens across the world. We hope that our results prove to be useful to optimise control strategies that could save lives and secure food security for the future.”

The paper is entitled ‘Azoles activate type I and type II programmed cell death pathways in crop pathogenic fungi’ and is published in Nature Communications. Co-authors are Dr Martin Schuster and Dr Sreedhar Kilaru at the University of Exeter.

END

The world-famous Roman Baths are home to a diverse range of microorganisms which could be critical in the global fight against antimicrobial resistance, a new study suggests.

The research, published in the journal The Microbe, is the first to provide a detailed examination of the bacterial and archaeal communities found within the waters of the popular tourist attraction in the city of Bath (UK).

Scientists collected samples of water, sediment and biofilm from locations within the Roman Baths complex including the King’s Spring (where the waters reach around 45°C) and the Great Bath, where the temperatures ...

A research team led by Dr. Choi Jeong Hee at the Korea Electrotechnology Research Institute (KERI) Battery Materials and Process Research Center, in cooperation with a Hanyang University team mentored by Professor Lee Jong-Won and a Kyunghee University team mentored by Professor Park Min-Sik, developed a core technology to ensure the charging/discharging stability and long-life of lithium-ion batteries under fast-charging conditions.

A crucial prerequisite for the widespread adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) is the enhancement of lithium-ion battery performance in terms of driving ...

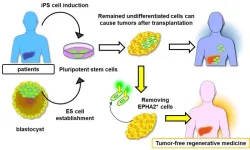

Ikoma, Japan – Pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) are a type of stem cells capable of developing into various cell types. Over the past few decades, scientists have been working towards the development of therapies using PSCs. Thanks to their unique ability to self-renew and differentiate (mature) into virtually any given type of tissue, PSCs could be used to repair organs that have been irreversibly damaged by age, trauma, or disease.

However, despite extensive efforts, regenerative therapies involving PSCs still have many hurdles to overcome. One being the formation of tumors (via ...

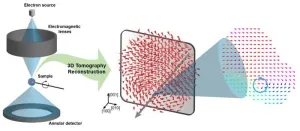

Materials that can maintain a magnetized state by themselves without an external magnetic field (i.e., permanent magnets) are called ferromagnets. Ferroelectrics can be thought of as the electric counterpart to ferromagnets, as they maintain a polarized state without an external electric field. It is well-known that ferromagnets lose their magnetic properties when reduced to nano sizes below a certain threshold. What happens when ferroelectrics are similarly made extremely small in all directions (i.e., into a zero-dimensional structure such as nanoparticles) has been a topic of controversy for a long time.

The research team led by Dr. Yongsoo ...

Little is known about the genetics and biology of chordoma, a rare and aggressive bone tumor. Chordomas occur in approximately one in a million people in the U.S. a year and only five percent of these are in children. These tumors can arise anywhere along the spine in adults. However, in children these tumors occur mostly at the base of the skull, making complete surgical removal challenging or impossible. Any tumor remnants are treated with high doses of radiation—which can cause significant damage to the developing brain.

A team of researchers led by Xiaowu Gai, PhD and Jaclyn Biegel, PhD, FACMG, at the Center for Personalized Medicine ...

According to research led by Prof. Varut Lohsiriwat, Professor of Surgery, Division of General Surgery (Section of Colorectal Surgery) of Siriraj Hospital, at Mahidol University, CRC is the third most common cancer in Thailand, accounting for 11% of the cancer burden. It is the only malignancy with an increased incidence in both genders in the country.

By 2040, the burden of CRC is projected to increase to 3.2 million new cases and 1.6 million deaths per year representing a 66% and 71% rise in new cases and deaths respectively relative ...

Speech and music are the dominant elements of an infant’s auditory environment. While past research has shown that speech plays a critical role in children’s language development, less is known about the music that infants hear.

A new University of Washington study, published May 21 in Developmental Science, is the first to compare the amount of music and speech that children hear in infancy. Results showed that infants hear more spoken language than music, with the gap widening as the babies get older.

“We wanted to get a snapshot of what’s happening in infants’ home environments,” said corresponding author ...

Research led by the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) has led to a new tool for forecasting coral disease that could help conservationists step in at the right times with key interventions. Ecological forecasts are critical tools for conserving and managing marine ecosystems, but few forecasting systems can account for the wide range of ecological complexities in near-real-time.

Using ecological and marine environmental conditions, the Multi-Factor Coral Disease Risk product predicts the risk of two diseases across reefs in the central and western Pacific and along the east coast of Australia. An article ...

Tobacco-funded research is still appearing in highly-cited medical journals - despite attempts by some to cut ties altogether, finds an investigation by The Investigative Desk and The BMJ today.

Although the tobacco industry has a long history of subverting science, most leading medical journals don’t have policies which ban research wholly or partly funded by the industry.

And even when publishers, authors and universities are willing to restrict tobacco industry ties, they struggle ...

Trout living in rivers polluted by metal from old mines across the British Isles are genetically “isolated” from other trout, new research shows.

Researchers analysed brown trout at 71 sites in Britain and Ireland, where many rivers contain metal washed out from disused mines.

While trout in metal-polluted rivers appear healthy, they are genetically distinct – and a lack of diversity in these populations makes them vulnerable to future threats.

By comparing the DNA of trout in rivers with and without metal pollution, the researchers found that metal-tolerant trout ...