Arctic melting heavily influenced by little-studied meteorological phenomena, find scientists led by UMass Amherst

Atmospheric blocking, especially over Scandinavia and the Ural Mountains, driving extreme Arctic weather events in Svalbard

2024-06-03

(Press-News.org) AMHERST, Mass. – A team of scientists led by François Lapointe, a research associate at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, has combined paleoclimatic data from the last 2,000 years with powerful computer modeling and in-the-field research on lake sediments and tree rings to show that an understudied phenomenon, known as atmospheric blocking, has long influenced temperature swings in the Arctic. As temperatures warm due to climate change, atmospheric blocking will help drive ever-wilder weather events. The study focused on the Norwegian Arctic archipelago, Svalbard, at the edge of the Arctic Ocean, and was published in Nature Communications.

It is well known that the Arctic is warming faster than the global average, a phenomenon known as Arctic Amplification. But, since 1991, Svalbard has experienced a warming trend that is double the Arcticwide rise in temperature. Consequently, the archipelago has been experiencing massive loss of ice, extreme rainfall events and landslides. “We wanted to know why Svalbard has been warming so much faster than the rest of the Arctic,” says Raymond Bradley, Distinguished Professor at UMass Amherst and co-author of the study, “and to figure out whether or not these trends would continue.”

To do so, they turned to lake sediments from Lake Linné, on the west coast of Svalbard, to help them reconstruct warm and wet conditions during the past 2,000 years. What makes this lake unique is the presence of instruments that have been deployed since 2012 by UMass Amherst alumnus and co-author, Michael Retelle, currently professor of earth and climate sciences at Bates College. These instruments track the precise timing of sediment entering the lake each year. Sediment pours into the lake during the increasingly frequent freak rainstorms.

Lapointe and his team looked at the calcium levels in Lake Linné’s sediments. Because much of the eastern terrain surrounding the lake is composed of carbonate-rich soil, intense rain events mean that carbonate washes into the lake, settles into the sediment on the lake bottom, and can be measured in sediment cores as a record of rainfall stretching back approximately 2,000 years.

When Lapointe and his colleagues compared all these historic and contemporary observations to the meteorological record, they found a stunning correlation.

“The biggest rain and warming events of the past are all linked to atmospheric blocking over Scandinavia and the Ural Mountains. Atmospheric blocking is when a high-pressure system, with air rotating clockwise around it, stalls over a particular region—in this case northern Scandinavia. In tandem with this high-pressure system, rain events in Svalbard are also often associated with a low-pressure system that settles in over Greenland, which rotates counter-clockwise,” Lapointe says. The two systems spin like a pair of intermeshed gears, drawing warmer, moister air up from the mid-Atlantic Ocean into the Arctic, leading to downpours of rain in Svalbard. Since observational measurements started, blocking in the Arctic has increased, as has Arctic warming.

“It will be very interesting to observe how atmospheric blocking behaves with further warming,” adds Lapointe. “Any further increase will likely amplify the effects of floods and natural hazards in Svalbard.”

Such projections for Svalbard’s future are concerning. Though the archipelago has a year-round population of just 2,650, the islands attracted over 130,000 visitors a year, drawn to their breathtaking landscapes and unique wildlife.

Contacts: Francois Lapointe, flapointe@umass.edu

Daegan Miller, drmiller@umass.edu

END

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2024-06-03

Nextdoor is the world’s largest hyperlocal social media network, used by 13% of American adults. Yet little is known about the make-up of the actual neighborhoods—numbering approximately 220,000 across the United States—in which these accounts exist and what people in those communities talk about on the platform.

To address our limited understanding of this population, a team of New York University and University of Michigan researchers generated a demographic portrait of communities in which Nextdoor neighborhoods exist, the presence of public agencies in those communities, and what topics are most often discussed. Using U.S. Census data, other publicly available ...

2024-06-03

Permafrost soils store large quantities of organic carbon and are often portrayed as a critical tipping element in the Earth system, which, once global warming has reached a certain level, suddenly and globally collapses. Yet this image of a ticking timebomb, one that remains relatively quiet until, at a certain level of warming, it goes off, is a controversial one among the research community. Based on the scientific data currently available, the image is deceptive, as an international team led by the Alfred Wegener Institute has shown in a recently released study. According to their findings, there is no single ...

2024-06-03

San Antonio, Texas – June 3, 2024 – Recognizing an unusual prevalence of bloodstream infections (BSI) that threatened extremely ill patients receiving Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, or ECMO, Tampa General Hospital (TGH) infection preventionists started an intervention that eliminated these infections completely from their 18-bed Cardiothoracic Intensive Care Unit (CTICU).

At the APIC 2024 Annual Conference, presenters from the 1,000-bed, tertiary care, academic medical system reported on how they reduced bloodstream infections in ECMO patients from a rate of 36% in October 2021 to a rate of 0% in April 2022. This rate was sustained for seven ...

2024-06-03

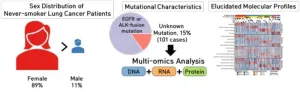

The primary cause of lung cancer is smoking. However, the incidence of lung cancer among never-smokers has been steadily increasing, especially among women. While approximately 80% of never-smoking lung cancer patients are prescribed targeted therapies that focus on mutations in proteins such as EGFR and ALK, the remaining patients often receive cytotoxic chemotherapy with high side effects and relatively low response rates, highlighting the urgent need for targeted therapies.

Dr. Lee Cheolju's ...

2024-06-03

Converting CO2 into fuel and chemicals using electricity, also known as electrochemical conversion of CO2, is a promising way to reduce emissions. This process allows us to use carbon captured from industries and the atmosphere and turn it into resources that we usually get from fossil fuels.

To advance ongoing research on efficient electrochemical conversion, scientists from Doshisha University have introduced a cost-effective method to produce valuable hydrocarbons from CO2. The study was made available online on 17 May 2024 and formally published in the journal Electrochimica Acta on 20 July 2024. The research team, led by Professor Takuya Goto and including Ms. Saya Nozaki from ...

2024-06-03

How can someone have alcohol intoxication without consuming alcohol? Auto-brewery syndrome, a rare condition in which gut fungi create alcohol through fermentation, is described in a case study in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal) https://www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.231319.

“Auto-brewery syndrome carries substantial social, legal, and medical consequences for patients and their loved ones,” writes Dr. Rahel Zewude, University of Toronto, with coauthors. “Our patient had several [emergency department] visits, was assessed by internists and psychiatrists, and was certified ...

2024-06-03

Implementing human papillomavirus (HPV)-based screening in British Columbia could eliminate cervical cancer in the province before 2040, according to a modelling study in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal) https://www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.231682.

More than 90% of cervical cancer cases worldwide are caused by 9 types of high-risk HPV. The World Health Organization and the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (CPAC) have both set targets to eliminate cervical cancer by 2040, defined as an annual rate of less than 4 per 100 000 women.

The Pap test has been the primary screening ...

2024-06-03

Berlin, Germany: While influenza infection is a significant public health threat, causing serious illness in between three and five million people worldwide per year and leading to about up to 650,000 deaths, the effectiveness of influenza vaccines varies considerably between individuals depending on vaccine types and individual circumstances. A person’s ability to resist infection (host immunity) plays an important role in this. Now, researchers have developed a way of classifying host immunity in individuals, which may lead to the early identification of those who will not respond well to a regular vaccine schedule and therefore ...

2024-06-03

Berlin, Germany: Aneuploidy (the presence of an abnormal number of chromosomes) in embryos is a major cause of impaired embryo development, leading to conditions such as Down syndrome, as well as to pregnancy loss. The transfer of such embryos in women undergoing IVF is therefore usually avoided because of unfavourable pregnancy outcomes. But mosaic embryos, comprising both genetically normal and abnormal cells, can result in perfectly normal babies. Now, researchers have been able to understand how these mosaic ...

2024-06-02

BOSTON—Metformin is safe to use during pregnancy to manage diabetes, with no long-term adverse effects on the children born and their mothers for at least 11 years after childbirth, according to research presented Sunday at ENDO 2024, the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in Boston, Mass. This is the first study to look at longer term effects of metformin use during pregnancy.

“Metformin has been extensively used for managing raised blood glucose values in pregnancy for many decades now. It is the only blood glucose-lowering oral medication approved ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Arctic melting heavily influenced by little-studied meteorological phenomena, find scientists led by UMass Amherst

Atmospheric blocking, especially over Scandinavia and the Ural Mountains, driving extreme Arctic weather events in Svalbard