(Press-News.org) Key takeaways

The movement of carbon between the atmosphere, oceans and continents — or carbon cycle — regulates Earth’s climate, with the ocean playing a major role in carbon sequestration.

A new study finds that the shape and depth of the ocean floor explain up to 50% of the changes in depth at which carbon has been sequestered there over the past 80 million years.

While these changes have been previously attributed to other causes, the new finding could inform ongoing efforts to combat climate change through marine carbon sequestration.

The movement of carbon between the atmosphere, oceans and continents — the carbon cycle — is a fundamental process that regulates Earth’s climate. Some factors, like volcanic eruptions or human activity, emit carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Others, such as forests and oceans, absorb that CO2. In a well-regulated system, the right amount of CO2 is emitted and absorbed to maintain a healthy climate. Carbon sequestration is one tactic in the current battle against climate change.

A new study finds that the shape and depth of the ocean floor explain up to 50% of the changes in depth at which carbon has been sequestered in the ocean over the past 80 million years. Previously, these changes have been attributed to other causes. Scientists have long known that the ocean, the largest absorber of carbon on Earth, directly controls the amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide. But, until now, exactly how changes in seafloor topography over Earth’s history affect the ocean’s ability to sequester carbon was not well understood.

“We were able to show, for the first time, that the shape and depth of the ocean floor play major roles in the long-term carbon cycle,” said Matthew Bogumil, the paper’s lead author and a UCLA doctoral student of earth, planetary and space sciences.

The long-term carbon cycle has a lot of moving parts, all functioning on different time scales. One of those parts is seafloor bathymetry — the mean depth and shape of the ocean floor. This is, in turn, controlled by the relative positions of the continent and the oceans, sea level, as well as the flow within Earth’s mantle. Carbon cycle models calibrated with paleoclimate datasets form the basis for scientists’ understanding of the global marine carbon cycle and how it responds to natural perturbations.

“Typically, carbon cycle models over Earth’s history consider seafloor bathymetry as either a fixed or a secondary factor,” said Tushar Mittal, the paper’s co-author and a professor of geosciences at Pennsylvania State University.

The new research, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reconstructed bathymetry over the last 80 million years and plugged the data into a computer model that measures marine carbon sequestration. The results showed that ocean alkalinity, calcite saturation state and the carbonate compensation depth depended strongly on changes to shallow parts of the ocean floor (about 600 meters or less) and on how deeper marine regions (greater than 1,000 meters) are distributed. These three measures are critical to understanding how carbon is stored in the ocean floor.

The researchers also found that for the current geologic era, the Cenozoic, bathymetry alone accounted for 33%–50% of the observed variation in carbon sequestration and concluded that by ignoring bathymetric changes, researchers mistakenly attribute changes in carbon sequestration to other, less certain factors, such as atmospheric CO2, water column temperature, and silicates and carbonates washed into the ocean by rivers.

“Understanding important processes in the long-term carbon cycle can better inform scientists working on marine-based carbon dioxide removal technologies to combat climate change today,” Bogumil said. “By studying what nature has done in the past, we can learn more about the possible outcomes and practicality of marine sequestration to mitigate climate change.”

This new understanding that the shape and depth of ocean floors is perhaps the greatest influencer of carbon sequestration can also aid the search for habitable planets in our universe.

“When looking at faraway planets, we currently have a limited set of tools to give us a hint about their potential for habitability,” said co-author Carolina Lithgow-Bertelloni, a UCLA professor and department chair of earth, planetary and space sciences. “Now that we understand the important role bathymetry plays in the carbon cycle, we can directly connect the planet’s interior evolution to its surface environment when making inferences from JWST observations and understanding planetary habitability in general.”

The breakthrough represents only the beginning of the researchers’ work.

“Now that we know how important bathymetry is in general, we plan to use new simulations and models to better understand how differently shaped ocean floors will specifically affect the carbon cycle and how this has changed over Earth’s history, especially the early Earth, when most of the land was underwater,” Bogumil said.

END

Shape and depth of ocean floor profoundly influence how carbon is stored there

New study finds seafloor topography accounts for up to 50% of the changes in depth at which carbon has been sequestered

2024-06-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Airplane noise exposure may increase risk of chronic disease

2024-06-03

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Monday, June 3, 2024

Contact:

Jillian McKoy, jpmckoy@bu.edu

Michael Saunders, msaunder@bu.edu

##

Airplane Noise Exposure May Increase Risk of Chronic Disease

A new study found that people who were exposed to higher levels of noise from aircraft were more likely to have a higher body mass index, an indicator for obesity that can lead to stroke or hypertension. The findings highlight how the environment—and environmental injustices—can shape health outcomes.

Research has shown that noise from airplanes and helicopters flying overhead are far more bothersome to people than noise from other modes of transportation, ...

Mental health, lack of workplace support are leading factors driving nurses from jobs

2024-06-03

Coworker and employer support are strong predictors of nurses planning to stay in their jobs, while symptoms of depression are linked to nurses planning to leave, according to a study conducted at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic by researchers at NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing.

The research—published in the Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, a journal of the American Nurses Association—examines both pandemic-related factors and the overall work environment for nurses and can help organizational ...

U.S. health departments experience workforce shortages and struggle to reach adequate staffing levels in public health

2024-06-03

Gaps persist in hiring enough U.S. public health workers and health departments continue to face challenges in recruiting new employees, according to a new study by Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and Indiana University. Insufficient funding, a shortage of people with public health training, and a lack of visibility for public careers, in addition to lengthy hiring processes, are cited as barriers contributing to an absence of progress for achieving a satisfactory level of workers. The results ...

Redox Science Meets Medicine at the 26th International Conference on Redox Medicine 2024 this June in Paris

2024-06-03

Redox Science Meets Medicine at the 26th International Conference on Redox Medicine 2024 this June in Paris

The 26th International Conference on Redox Medicine 2024 will take place this month, on June 27-28 at Fondation Biermans-Lapôtre in Paris, France.

With 41+ communications and participants from 20 different countries, the conference promises a diverse exchange of knowledge and ideas.

The sessions of the conference are organized around key topics, with each speaker addressing a specific ...

Albert Einstein College of Medicine names Marla Keller, MD, Executive Dean

2024-06-03

June 3, 2024—(BRONX, NY)—Marla Keller, M.D., a national leader in academic medicine and in clinical and translational research and training, has been appointed executive dean at Albert Einstein College of Medicine. In this role, Dr. Keller will work closely with Yaron Tomer, M.D., the Marilyn and Stanley M. Katz Dean at Einstein, other executive leaders at the College of Medicine and Montefiore, and the Board of Trustees to achieve the vision for the institution. As Einstein’s second most senior officer, she will drive strategic planning for the College of Medicine and provide guidance across all academic and research programs.

Dr. ...

Two-pronged attack strategy boosts immunotherapy in preclinical studies

2024-06-03

JUNE 3, 2024, NEW YORK – A novel immunotherapy approach developed by Ludwig Cancer Research scientists employs a two-pronged attack against solid tumors to boost the immune system’s ability to target and eliminate cancer cells.

The research focuses on an immunotherapy called adoptive cell transfer (ACT), which involves extracting T cells from a patient, enhancing their ability to fight cancer, expanding them in culture and reinfusing them into the patient’s body.

“While T cell therapies have shown tremendous ...

Microscopic defects in ice shape how massive glaciers flow, study shows

2024-06-03

As they seep and calve into the sea, melting glaciers and ice sheets are raising global water levels at unprecedented rates. To predict and prepare for future sea-level rise, scientists need a better understanding of how fast glaciers melt and what influences their flow.

Now, a study by MIT scientists offers a new picture of glacier flow, based on microscopic deformation in the ice. The results show that a glacier’s flow depends strongly on how microscopic defects move through the ice.

The researchers found they could estimate ...

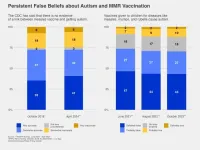

False belief in MMR vaccine-autism link endures as measles threat persists

2024-06-03

As measles cases rise across the United States and vaccination rates for the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine continue to fall, a new survey finds that a quarter of U.S. adults do not know that claims that the MMR vaccine causes autism are false.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has said there is no evidence linking the measles vaccine and getting autism. But 24% of U.S. adults do not accept that – they say that statement is somewhat or very inaccurate – and another 3% are not sure, according to the survey by the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) of the University of Pennsylvania. About three-quarters of those surveyed ...

Type of weight loss surgery women undergo before pregnancy may influence children’s weight gain

2024-06-03

BOSTON—The type of weight loss surgery women undergo before becoming pregnant may affect how much weight their children gain in the first three years of life, suggests a study being presented Monday at ENDO 2024, the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in Boston, Mass.

Researchers found children born to women who underwent the bariatric procedure known as sleeve gastrectomy before they became pregnant gain more weight per month on average in the first three years of life compared with children born to women who had the less common ...

Meditating with headband that tracks brain activity may improve surgical recovery in patients with Cushing’s

2024-06-03

BOSTON—Patients with Cushing’s syndrome who are recovering from surgery and wear a headband that tracks brain activity while they meditate may have less pain and better physical functioning compared with patients not using the device, suggests a study being presented Monday at ENDO 2024, the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in Boston, Mass.

The headband, called MUSE-2, uses electroencephalogram (EEG) sensors to measure brain activity and provides audio biofeedback while a person meditates.

Cushing's syndrome is a rare ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

AI biases can influence people’s perception of history

Prenatal opioid exposure and well-being through adolescence

Big and small dogs both impact indoor air quality, just differently

Wearing a weighted vest to strengthen bones? Make sure you’re moving

Microbe survives the pressures of impact-induced ejection from Mars

Asteroid samples offer new insights into conditions when the solar system formed

Fecal transplants from older mice significantly improve ovarian function and fertility in younger mice

Delight for diastereomer production: A novel strategy for organic chemistry

Permafrost is key to carbon storage. That makes northern wildfires even more dangerous

Hairdressers could be a secret weapon in tackling climate change, new research finds

Genetic risk for mental illness is far less disorder-specific than clinicians have assumed, massive Swedish study reveals

A therapeutic target that would curb the spread of coronaviruses has been identified

Modern twist on wildfire management methods found also to have a bonus feature that protects water supplies

AI enables defect-aware prediction of metal 3D-printed part quality

Miniscule fossil discovery reveals fresh clues into the evolution of the earliest-known relative of all primates

World Water Day 2026: Applied Microbiology International to hold Gender Equality and Water webinar

The unprecedented transformation in energy: The Third Energy Revolution toward carbon neutrality

Building on the far side: AI analysis suggests sturdier foundation for future lunar bases

Far-field superresolution imaging via k-space superoscillation

10 Years, 70% shift: Wastewater upgrades quietly transform river microbiomes

Why does chronic back pain make everyday sounds feel harsher? Brain imaging study points to a treatable cause

Video messaging effectiveness depends on quality of streaming experience, research shows

Introducing the “bloom” cycle, or why plants are not stupid

The Lancet Oncology: Breast cancer remains the most common cancer among women worldwide, with annual cases expected to reach over 3.5 million by 2050

Improve education and transitional support for autistic people to prevent death by suicide, say experts

GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic could cut risk of major heart complications after heart attack, study finds

Study finds Earth may have twice as many vertebrate species as previously thought

NYU Langone orthopedic surgeons present latest clinical findings and research at AAOS 2026

New journal highlights how artificial intelligence can help solve global environmental crises

Study identifies three diverging global AI pathways shaping the future of technology and governance

[Press-News.org] Shape and depth of ocean floor profoundly influence how carbon is stored thereNew study finds seafloor topography accounts for up to 50% of the changes in depth at which carbon has been sequestered