The finding, by CNIO researchers, are published in Nature Aging. It suggests that an intervention on the inflammation alone can relieve symptoms and increase survival.

The research has been conducted on animal models, but comparing their molecular processes with blood samples from people in their seventies indicates that they can be extrapolated to human aging. The reality of a population who is ageing at an accelerated rate makes it a priority to understand what happens in the body over time, on a molecular scale. The mTOR protein complex is known to be involved in many processes, as a key agent in multiple functions of the body and especially in metabolism.

A new paper finds now in animal models that when mTOR activity is just slightly increased, ageing set earlier on, and the lifetime of animals can be shortened by up to 20%.

Given the central role of mTOR in metabolism, this research provides some clues to understand why ageing-related diseases appear or worsen in people with a high body mass index, an indicator related to obesity and inflammation. It also sheds light on why calorie restriction –a type of diet associated with increased longevity in animals– can promote healthy ageing, as certain genes activated by limiting nutrient intake interact with mTOR.

In addition, it comes up with a new research tool created “to study the relationship between nutrient increase and the ageing of different organs,” says lead author Alejo Efeyan, head of the Metabolism and Cell Signalling Group at the National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO).

The paper is published in Nature Aging. The first author is Ana Ortega-Molina, who currently runs the Metabolism in Cancer and Ageing Laboratory at the Severo Ochoa Molecular Biology Centre (CBM). Other co-authors are Rafael de Cabo of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) in Bethesda, USA, Consuelo Borrás and Daniel Monleón, from the University of Valencia, and María Casanova-Acebes, head of the Cancer Immunity group at CNIO.

Premature ageing in animals that ‘believe’ to be eating more than they do

The activity of the mTOR protein complex is regulated according to the amount of nutrients available in the cell. The authors of this study devised a system to trick mTOR, and thus regulate its activity at will in animal models.

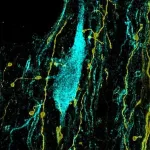

The inside of cells is a continuous coming and going of chemical signals, which are transmitted thanks to proteins (of course the cells also communicate with each other, through intercellular signalling). The mTOR protein complex is a key agent in the large cellular communication highway involved in harnessing energy: cell metabolism. We also know that mTOR influences longevity, although we do not yet fully understand how.

To manipulate the activity of mTOR at will, the CNIO team focused not on mTOR itself, but on the protein that should send the signal indicating the amount of nutrients available in the cell. The researchers genetically modified this protein to get it to lie and signal to mTOR that there are more nutrients in the cell than there actually are.

Thus, the chemical signal pathway of mTOR is activated as if the animals are eating more, although in reality their diet does not vary.

When animals with this protein, which tricks mTOR, reach maturity, the functioning of the cells begins to fail and characteristic symptoms of ageing are detected: the skin becomes thinner, and damage occurs in the pancreas, liver, kidneys and other organs. Immune system cells come to repair them but are overwhelmed by the amount of damage. They accumulate and, instead of repairing, trigger inflammation that further increases problems in those organs.

The result of this vicious circle is that the lifespan of these animals in which mTOR is working harder than normal is shortened by 20%, which on the human scale would be equivalent to about 16 years.

The study sought to cut this circle by blocking the immune response that causes inflammation. Damage in the organs then improved enough to gain what in humans would be a few years of life.

For this reason, the authors state that acting on chronic inflammation is “a potential therapeutic measure that controls deterioration of health,” says Ortega-Molina

Results can also apply to humans

What happens when acting on the information that mTOR receives, simulating an excess of nutrients, is reminiscent of a change that occurs during natural ageing. The CNIO group compared its model to colonies of naturally ageing mice, both its own and those belonging to the National Institute on Aging (NIA).

For example, the activity of lysosomes, which are the organelles with which the cell removes and recycles its waste, is reduced in both naturally aged and genetically modified animals. “When there is an excess of nutrients it makes sense that the cell shuts down the recycling activity of lysosomes, because this recycling operates especially when there are no nutrients,” Efeyan says.

This decrease in lysosomal activity also occurs in human ageing, as verified by the group from the University of Valencia when contrasting blood samples from young people and septuagenarians.

A new tool

Beyond this paper, Efeyan believes that this new animal model offers “ample fertile ground to ask more questions about how nutrient increase, or their signalling, facilitates processes in the different organs that allow us to understand their ageing in particular. Or, for example, investigate the relationship with neurodegenerative diseases, because there is some inflammation in the central nervous system. It’s a tool that many more people can use.”

Funding

This work has been funded by, among others, the Spanish Ministry for Science, Innovation and Universities, the Spanish Research Agency, European Regional Development Fund, Spanish Association Against Cancer Research Scientific Foundation, “la Caixa” Banking Foundation, Olivia Roddom Oncology Research Grant, Intramural Research Program at the NIA, National Institutes of Health. Yurena Vivas, one of the authors, is beneficiary of a CNIO Friends contract funded by the Domingo Martinez Foundation.

END