Northwestern University researchers have developed a new antioxidant biomaterial that someday could provide much-needed relief to people living with chronic pancreatitis.

The study will be published on June 7 in the journal Science Advances.

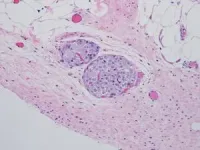

Before surgeons remove the pancreas from patients with severe, painful chronic pancreatitis, they first harvest insulin-producing tissue clusters, called islets, and transplant them into the vasculature of the liver. The goal of the transplant is to preserve a patient’s ability to control their own blood-glucose levels without insulin injections.

Unfortunately, the process inadvertently destroys 50-80% of islets, and one-third of patients become diabetic after surgery. Three years post-surgery, 70% of patients require insulin injections, which are accompanied by a list of side effects, including weight gain, hypoglycemia and fatigue.

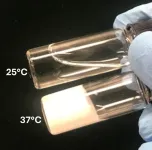

In the new study, researchers transplanted islets from the pancreas to the omentum — the large, flat, fatty tissue that covers the intestines — instead of the liver. And, to create a healthier microenvironment for the islets, the researchers adhered the islets to the omentum with an inherently antioxidant and anti-inflammatory biomaterial, which rapidly transforms from a liquid to a gel when exposed to body temperature.

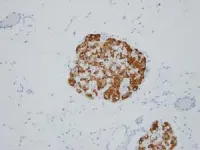

In studies with mouse and non-human primates, the gel successfully prevented oxidative stress and inflammatory reactions, significantly improving survival and preserving function of transplanted islets. It marks the first time a synthetic antioxidant gel has been used to preserve function of transplanted islets.

“Although islet transplantation has improved over the years, long-term outcomes remain poor,” said Northwestern’s Guillermo A. Ameer, who led the study. “There is clearly a need for alternative solutions. We have engineered a cutting-edge synthetic material that provides a supportive microenvironment for islet function. When tested in animals, we were successful. It kept islet function maximized and restored normal blood sugar levels. We also report a reduction in units of insulin that animals required.”

“With this new approach, we hope that patients will no longer have to choose between living with the physical pain of chronic pancreatitis or the complications of diabetes,” added Jacqueline Burke, a research assistant professor of biomedical engineering at Northwestern and the paper’s first author.

An expert in regenerative engineering, Ameer is the Daniel Hale Williams Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering, a Professor of Surgery at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and founding director of the Center for Advanced Regenerative Engineering.

‘Compromised quality of life’

For patients living without a pancreas, side effects such as managing blood-sugar levels can be a lifelong struggle. By secreting insulin in response to glucose, islets help the body maintain glycemic control. Without functioning islets, people must closely monitor their blood-sugar levels and frequently inject insulin.

“Living without functional islets places a great burden on patients,” Burke said. “They must learn to count carbs, dose insulin at the appropriate time and continuously monitor blood glucose. This consumes much of their time and mental energy. Even with great care, exogeneous insulin therapy is not as effective as islets for maintaining glucose control. Patients with out-of-range blood glucose will develop complications, such as blindness and amputation. Our goal is for this biomaterial to preserve the islets, so patients can live a normal life — a life without diabetes.”

“It’s a compromised quality of life,” Ameer said. “Instead of multiple insulin injections, we would love to collect and preserve as many islets as possible.”

But, unfortunately, the current standard of care for preserving islets often leads to poor outcomes. After the surgery to remove the pancreas, surgeons isolate islets from the pancreas and transplant them to the liver through portal vein infusion. This intraportal perfusion procedure has several common complications. Islets in direct contact with blood flow undergo an inflammatory response, more than half of the islets die, and transplanted islets can cause dangerous clots in the liver. For those reasons, physicians and researchers have been searching for an alternate transplantation site.

In previous clinical studies, researchers transplanted islets to the omentum instead of the liver in order to bypass issues with clotting. To secure the islets on the omentum, physicians used plasma from the patients’ own blood to form a biologic gel. While the omentum appeared to work better than the liver as a transplantation site, several issues, including clots and inflammation, remained.

“There’s been significant interest in the research and medical communities to find an alternate islet transplantation site,” Ameer said. “The results from the omentum study were encouraging, but outcomes were varied. We believe that’s because the use of the patients’ blood and the added components required to create the biologic gel can affect reproducibility among patients.”

A citrate solution

To protect the islets and improve outcomes, Ameer turned to the citrate-based biomaterials platform with inherent antioxidant properties developed in his laboratory. Used in products approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration for musculoskeletal surgeries, citrate-based biomaterials have demonstrated the ability to control the body’s inflammatory responses. Ameer set out to investigate whether a version of these biomaterials with biodegradable and temperature-responsive phase-changing properties would provide a superior alternative to a biologic gel obtained from blood.

In cell cultures, both mouse and human islets stored within the citrate-based gel maintained viability much longer than islets in other solutions. When exposed to glucose, the islets secreted insulin, demonstrating normal functionality. Moving beyond cell cultures, Ameer’s team tested the gel in small and large animal models. Liquid at room temperature, the material turns into a gel at body temperature, so it’s simple to apply and easily stays in place.

In the animal studies, the gel effectively secured the islets onto the omentum of the animals. Compared to the current methods, more islets survived, and, over time, the animals restored normal blood glucose levels. According to Ameer, the success is partially due to the new material’s biocompatibility and antioxidant nature.

“Islets are very sensitive to oxygen,” Ameer said. “They are affected by both too little oxygen and too much oxygen. The material’s innate antioxidant properties protect the cells. Plasma from your own blood doesn’t offer the same level of protection.”

Integrating into tissues

After about three months, the body resorbed 80-90% of the biocompatible gel. But, at that point, it was no longer needed.

“What was fascinating is that the islets regenerated blood vessels,” Ameer said. “The body generated a network of new blood vessels to reconnect the islets with the body. That is a major breakthrough because the blood vessels keep the islets alive and healthy. Meanwhile, our gel is simply resorbed into the surrounding tissue, leaving little evidence behind.”

Next, Ameer aims to test his hydrogel in animal models over a longer period of time. He said the new hydrogel also could be used for various cell replacement therapies, including stem cell-derived beta cells for treating diabetes.

The study, “Phase-changing citrate macromolecule combats oxidative pancreatic islet damage, enables islet engraftment and function in the omentum,” was supported by the U.S. Department of Defense and the National Science Foundation.

END