(Press-News.org) For hundreds of years, the clarity and magnification of microscopes were ultimately limited by the physical properties of their optical lenses. Microscope makers pushed those boundaries by making increasingly complicated and expensive stacks of lens elements. Still, scientists had to decide between high resolution and a small field of view on the one hand or low resolution and a large field of view on the other.

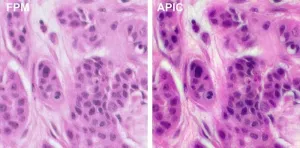

In 2013, a team of Caltech engineers introduced a microscopy technique called FPM (for Fourier ptychographic microscopy). This technology marked the advent of computational microscopy, the use of techniques that wed the sensing of conventional microscopes with computer algorithms that process detected information in new ways to create deeper, sharper images covering larger areas. FPM has since been widely adopted for its ability to acquire high-resolution images of samples while maintaining a large field of view using relatively inexpensive equipment.

Now the same lab has developed a new method that can outperform FPM in its ability to obtain images free of blurriness or distortion, even while taking fewer measurements. The new technique, described in a paper that appeared in the journal Nature Communications, could lead to advances in such areas as biomedical imaging, digital pathology, and drug screening.

The new method, dubbed APIC (for Angular Ptychographic Imaging with Closed-form method), has all the advantages of FPM without what could be described as its biggest weakness—namely, that to arrive at a final image, the FPM algorithm relies on starting at one or several best guesses and then adjusting a bit at a time to arrive at its "optimal" solution, which may not always be true to the original image.

Under the leadership of Changhuei Yang, the Thomas G. Myers Professor of Electrical Engineering, Bioengineering, and Medical Engineering and an investigator with the Heritage Medical Research Institute, the Caltech team realized that it was possible to eliminate this iterative nature of the algorithm.

Rather than relying on trial and error to try to home in on a solution, APIC solves a linear equation, yielding details of the aberrations, or distortions introduced by a microscope's optical system. Once the aberrations are known, the system can correct for them, basically performing as though it is ideal, and yielding clear images covering large fields of view.

"We arrive at a solution of the high-resolution complex field in a closed-form fashion, as we now have a deeper understanding in what a microscope captures, what we already know, and what we need to truly figure out, so we don't need any iteration,” says Ruizhi Cao (PhD '24), co-lead author on the paper, a former graduate student in Yang's lab, and now a postdoctoral scholar at UC Berkeley. "In this way, we can basically guarantee that we are seeing the true final details of a sample."

As with FPM, the new method measures not only the intensity of the light seen through the microscope but also an important property of light called “phase,” which is related to the distance that light travels. This property goes undetected by human eyes but contains information that is very useful in terms of correcting aberrations. It was in solving for this phase information that FPM relied on a trial-and-error method, explains Cheng Shen (PhD '23), co-lead author on the APIC paper, who also completed the work while in Yang's lab and is now a computer vision algorithm engineer at Apple. "We have proven that our method gives you an analytical solution and in a much more straightforward way. It is faster, more accurate, and leverages some deep insights about the optical system."

Beyond eliminating the iterative nature of the phase-solving algorithm, the new technique also allows researchers to gather clear images over a large field of view without repeatedly refocusing the microscope. With FPM, if the height of the sample varied even a few tens of microns from one section to another, the person using the microscope would have to refocus in order to make the algorithm work. Since these computational microscopy techniques frequently involve stitching together more than 100 lower-resolution images to piece together the larger field of view, that means APIC can make the process much faster and prevent the possible introduction of human error at many steps.

"We have developed a framework to correct for the aberrations and also to improve resolution,” says Cao. "Those two capabilities can be potentially fruitful for a broader range of imaging systems."

Yang says the development of APIC is vital to the broader scope of work his lab is currently working on to optimize image data input for artificial intelligence (AI) applications. "Recently, my lab showed that AI can outperform expert pathologists at predicting metastatic progression from simple histopathology slides from lung cancer patients," says Yang. "That prediction ability is exquisitely dependent on obtaining uniformly in-focus and high-quality microscopy images, something that APIC is highly suited for."

The paper, titled, "High-resolution, large field-of-view label-free imaging via aberration-corrected, closed-form complex field reconstruction" appeared online in Nature Communications on June 3. The work was supported by the Heritage Medical Research Institute.

For hundreds of years, the clarity and magnification of microscopes were ultimately limited by the physical properties of their optical lenses. Microscope makers pushed those boundaries by making increasingly complicated and expensive stacks of lens elements. Still, scientists had to decide between high resolution and a small field of view on the one hand or low resolution and a large field of view on the other.

In 2013, a team of Caltech engineers introduced a microscopy technique called FPM (for Fourier ptychographic microscopy). This technology marked the advent of computational microscopy, the use of techniques that wed the sensing of conventional microscopes with computer algorithms that process detected information in new ways to create deeper, sharper images covering larger areas. FPM has since been widely adopted for its ability to acquire high-resolution images of samples while maintaining a large field of view using relatively inexpensive equipment.

Now the same lab has developed a new method that can outperform FPM in its ability to obtain images free of blurriness or distortion, even while taking fewer measurements. The new technique, described in a paper that appeared in the journal Nature Communications, could lead to advances in such areas as biomedical imaging, digital pathology, and drug screening.

The new method, dubbed APIC (for Angular Ptychographic Imaging with Closed-form method), has all the advantages of FPM without what could be described as its biggest weakness—namely, that to arrive at a final image, the FPM algorithm relies on starting at one or several best guesses and then adjusting a bit at a time to arrive at its "optimal" solution, which may not always be true to the original image.

Under the leadership of Changhuei Yang, the Thomas G. Myers Professor of Electrical Engineering, Bioengineering, and Medical Engineering and an investigator with the Heritage Medical Research Institute, the Caltech team realized that it was possible to eliminate this iterative nature of the algorithm.

Rather than relying on trial and error to try to home in on a solution, APIC solves a linear equation, yielding details of the aberrations, or distortions introduced by a microscope's optical system. Once the aberrations are known, the system can correct for them, basically performing as though it is ideal, and yielding clear images covering large fields of view.

"We arrive at a solution of the high-resolution complex field in a closed-form fashion, as we now have a deeper understanding in what a microscope captures, what we already know, and what we need to truly figure out, so we don't need any iteration,” says Ruizhi Cao (PhD '24), co-lead author on the paper, a former graduate student in Yang's lab, and now a postdoctoral scholar at UC Berkeley. "In this way, we can basically guarantee that we are seeing the true final details of a sample."

As with FPM, the new method measures not only the intensity of the light seen through the microscope but also an important property of light called “phase,” which is related to the distance that light travels. This property goes undetected by human eyes but contains information that is very useful in terms of correcting aberrations. It was in solving for this phase information that FPM relied on a trial-and-error method, explains Cheng Shen (PhD '23), co-lead author on the APIC paper, who also completed the work while in Yang's lab and is now a computer vision algorithm engineer at Apple. "We have proven that our method gives you an analytical solution and in a much more straightforward way. It is faster, more accurate, and leverages some deep insights about the optical system."

Beyond eliminating the iterative nature of the phase-solving algorithm, the new technique also allows researchers to gather clear images over a large field of view without repeatedly refocusing the microscope. With FPM, if the height of the sample varied even a few tens of microns from one section to another, the person using the microscope would have to refocus in order to make the algorithm work. Since these computational microscopy techniques frequently involve stitching together more than 100 lower-resolution images to piece together the larger field of view, that means APIC can make the process much faster and prevent the possible introduction of human error at many steps.

"We have developed a framework to correct for the aberrations and also to improve resolution,” says Cao. "Those two capabilities can be potentially fruitful for a broader range of imaging systems."

Yang says the development of APIC is vital to the broader scope of work his lab is currently working on to optimize image data input for artificial intelligence (AI) applications. "Recently, my lab showed that AI can outperform expert pathologists at predicting metastatic progression from simple histopathology slides from lung cancer patients," says Yang. "That prediction ability is exquisitely dependent on obtaining uniformly in-focus and high-quality microscopy images, something that APIC is highly suited for."

The paper, titled, "High-resolution, large field-of-view label-free imaging via aberration-corrected, closed-form complex field reconstruction" appeared online in Nature Communications on June 3. The work was supported by the Heritage Medical Research Institute.

END

New computational microscopy technique provides more direct route to crisp images

Caltech's new analytical method eliminates guesswork, leading to true high-resolution images covering a large field of view

2024-06-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

11th-grade student wins competition with research conducted at UTA

2024-06-28

A Plano high school student conducting research in a University of Texas at Arlington chemistry professor’s lab earned multiple awards at the annual Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). Regeneron ISEF is the world’s largest pre-college STEM competition for students in grades 9-12.

Chloe Lee, a junior in the International Baccalaureate program at Plano East Senior High School, conducted research in the lab of Junha Jeon, associate professor of chemistry and ...

Deep learning-assisted lesion segmentation in PET/CT imaging: A feasibility study for salvage radiation therapy in prostate cancer

2024-06-28

“The deployment of DL segmentation methods in 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT imaging represents an intriguing research direction for precision medicine in salvage prostate cancer care.”

BUFFALO, NY- June 28, 2024 – A new editorial paper was published in Oncoscience (Volume 11) on May 20, 2024, entitled, “Deep learning-assisted lesion segmentation in PET/CT imaging: A feasibility study for salvage radiation therapy in prostate cancer.”

In this new editorial, researchers Richard L.J. Qiu, Chih-Wei Chang, ...

Dementia cost calculator will provide precise, annual, national estimates of Alzheimer's financial toll

2024-06-28

An A-list of researchers from across USC is building a dementia cost model that will generate comprehensive national, annual estimates of the cost of dementia that could benefit patients and their families, thanks to a five-year, $8.2 million federal grant from the National Institute on Aging.

A firm grip on the costs of the disease could assist families living with dementia with planning their budgets and support needs, inform treatment and caregiving options, and help shape health care policy.

“We currently have estimates for a particular ...

Moffitt researchers develop synthesis method to enhance access to cancer-fighting withanolides

2024-06-28

TAMPA, Fla. — Withanolides, a class of naturally occurring compounds found in plants, have long been a focus of cancer research due to their ability to inhibit cancer cell growth, induce cell death and prevent metastasis. These compounds are important in developing new cancer treatments. However, the difficulty of obtaining enough of these compounds from plants has hindered research and therapeutic development.

Moffitt Cancer Center researchers have developed a groundbreaking method for the scalable synthesis of withanolides. This innovative approach, published in Science Advances, could revolutionize cancer research by providing ...

Analysis of NASA InSight data suggests Mars hit by meteoroids more often than thought

2024-06-28

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — NASA’s Mars InSight Lander may be resting on the Red Planet in retirement, but data from the robotic explorer is still leading to seismic discoveries on Earth.

In one of the latest studies using data from the spacecraft, an international team of scientists led by a Brown University researcher found that Mars may be getting bombarded by space rocks at more frequent rates than previously thought. Impact rates could be two to 10 times higher than previously estimated, depending on the size of the meteoroids, according to the study published in Science Advances.

“It’s ...

Serotonin 2C receptor regulates memory in mice and humans – implications for Alzheimer’s disease

2024-06-28

Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine, the University of Cambridge in the U.K. and collaborating institutions have shown that serotonin 2C receptor in the brain regulates memory in people and animal models. The findings, published in the journal Science Advances, not only provide new insights into the factors involved in healthy memory but also in conditions associated with memory loss, like Alzheimer’s disease, and suggest novel avenues for treatment.

“Serotonin, a compound produced by neurons in the midbrain, acts as a neurotransmitter, passing messages between brain cells,” said co-corresponding author Dr. Yong Xu, professor of pediatrics ...

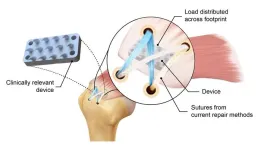

New device inspired by python teeth doubles strength of rotator cuff repairs

2024-06-28

New York, NY—June 24, 2024—Most people, when they think about pythons, visualize the huge snake constricting and swallowing victims whole. But did you know that pythons initially hold onto their prey with their sharp, backward-curving teeth? Medical researchers have long been aware that these teeth are perfect for grasping soft tissue rather than cutting through it, but no one has yet been able to put this concept into surgical practice. Over the years, mimicking these teeth for use in surgery has been a frequent topic ...

The beginnings of fashion

2024-06-28

EMBARGO: 4:00 Sydney AEST June 29 | 14:00 US ET June 28 2024

The beginnings of fashion

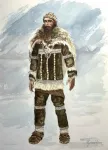

Paleolithic eyed needles and the evolution of dress

A team of researchers led by an archaeologist at the University of Sydney are the first to suggest that eyed needles were a new technological innovation used to adorn clothing for social and cultural purposes, marking the major shift from clothes as protection to clothes as an expression of identity.

“Eyed needle tools are an important development in prehistory because they document a transition in the function of clothing from utilitarian to social purposes,” says Dr Ian Gilligan, Honorary Associate ...

Why some tumors are resistant to cell therapies

2024-06-28

FRANKFURT. In congratulating the CARISMa scientists, Goethe University President Prof. Enrico Schleiff said: “The new LOEWE network sets up in Hesse an innovative research program that is currently gathering steam all over the world. It also expands Goethe University’s existing research profile and broadens our network of cooperation partners in the field of CAR cell therapy [editor’s note: CAR is the abbreviation for chimeric antigen receptor]. The network deliberately builds on our university’s ...

Can A.I. tell you if you have osteoporosis? Newly developed deep learning model shows promise

2024-06-28

Osteoporosis is so difficult to detect in early stage it’s called the “silent disease.” What if artificial intelligence could help predict a patient’s chances of having the bone-loss disease before ever stepping into a doctor’s office?

Tulane University researchers made progress toward that vision by developing a new deep learning algorithm that outperformed existing computer-based osteoporosis risk prediction methods, potentially leading to earlier diagnoses and better outcomes for patients with osteoporosis risk.

Their results were recently published in ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Evidence behind intermittent fasting for weight loss fails to match hype

How AI tools like DeepSeek are transforming emotional and mental health care of Chinese youth

Study finds link between sugary drinks and anxiety in young people

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

[Press-News.org] New computational microscopy technique provides more direct route to crisp imagesCaltech's new analytical method eliminates guesswork, leading to true high-resolution images covering a large field of view