(Press-News.org) A multi-institutional team that includes researchers from the University of Delaware, University of California San Diego and Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI), among others, published a paper in Science on Thursday, June 27, that provides new insight on how deep-sea “comb jellies” called ctenophores adapt and survive at extreme pressures.

It turns out that part of the adaptation involves lipids, fatty chemical compounds found in the membrane of all living cells that perform essential functions, including storing energy, sending signals and controlling what passes through the cell membrane.

The work provides new knowledge about how marine organisms can adapt and survive in the ocean, now and potentially into the future. It also may inform what’s known about the human body — in particular, how a specific lipid called plasmalogen found in nerve cells might work in our brains.

UD biophysicist Edward Lyman and doctoral students Sasiri Vargas-Urbano and Miguel Pedraza Joya are among the co-authors on the paper. Other co-authors include first-author Jacob Winnikoff, a researcher at MBARI and University of California, Santa Cruz and San Diego, now at Harvard University, Steven Haddock, an MBARI marine biologist, and the project principal investigator Itay Budin, an assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry at UC San Diego. Additional collaborators include researchers from UCSD Health Sciences, University of California Santa Cruz, the National Institutes of Health and Cornell Center for High Energy X-ray Sciences.

Adapting under extreme pressure

Ctenophores are predators found at various depths in the ocean, where they help regulate the marine ecosystem by eating fish and shellfish larvae, while serving as a food source for other marine animals. If you go back in time, UD’s Lyman said, the first thing that branches off from the rest of the animals is the ctenophores — a result just established last year by co-author Haddock.

“This means that you and I are more closely related to a jellyfish than a jellyfish is to a ctenophore,” Lyman said.

The deep ocean, meanwhile, is characterized by low temperature and high pressure. Lyman explained that ctenophores are great for teasing apart this problem of how marine organisms adapt to extreme pressure environments because there are multiple ctenophore species that live at the surface, up to two and half miles deep in the ocean, and only at the surface in the Arctic, where the temperature is generally the same as in the deep sea.

“Studying ctenophores, you can compare those organisms in a way that’s roughly controlled for temperature and now you can look at how the organism adapts only to changes in pressure,” said Lyman, a UD professor of physics and astronomy with expertise using molecular dynamics simulations to characterize lipids.

Haddock’s team at MBARI collected samples of 17 different species of ctenophores that live in different parts of the ocean and Budin’s lab analyzed their lipidomes — the chemical species found in the cell membrane — in an extensive survey.

In the work, the collaborative researchers compared the chemical composition of shallow- and deep-sea dwelling ctenophores and found an adaptation in the cellular membrane of those living in the deep that enables them to survive under extreme pressures. Budin’s preliminary research revealed that deep-sea ctenophores have a huge abundance of a particular type of lipid molecule called plasmalogen, which is present in our own membranes in small amounts.

“What makes plasmalogen lipids interesting is that they allow cell membranes to bend and deform, even in the deep ocean at high pressure, where membranes would otherwise be very stiff, and that's a useful adaptation,” said Lyman.

Of molecules and membranes

A fundamental function of membranes is to let things in and out a cell or to enable cell division to replicate genetic material. To do this, the cell membrane must go from a generally flat state to one that is highly curved, so the researchers ran experiments and simulations to measure the shape of plasmalogen molecules under different conditions. This is because while all membranes are made from a mixture of different kinds of lipids, it’s the chemistry of a lipid molecule that determines whether it wants to reside in a membrane that's flat or curved.

UD’s Vargas-Urbano leveraged molecular dynamics and the massive computational power of National Science Foundation supercomputers to model all the structures inside the ctenophore membranes and simulate how the molecules would move and interact with each other at high pressures. The process took a great deal of time.

“Simulations that are about 500 nanoseconds long could take about a month to create from the data,” said Vargas-Urbano. That’s the equivalent of a movie clip that lasts about 500 billionths of a second.

Meanwhile, Budin and Winnikoff used a special X-ray scattering beam line at Cornell to experimentally study how the structure of ctenophore membranes changed under various pressures. Looking at the structural properties of the lipid mixtures directly from the organisms at high-pressure was a crucial part of the project that helped the researchers discern that ctenophore lipidomes are specialized for high pressure.

The deep sea is under extreme pressures equal to that of hundreds of atmospheres, due to the weight of the water that lies above. Budin’s team at UC San Diego learned that if they exposed the cell membrane of E. coli, a human gut bacteria, to pressures found where the deepest ctenophore live (roughly 500 times the water pressure found on the ocean surface) then the microbes’ growth was severely restricted, Lyman said. However, when the researchers gave E. coli the ability to synthesize plasmalogen lipids and pressurized them the same way, then the cells could grow and divide normally.

Simulating the membrane in the computer and testing it under various temperatures and pressures across various timeframes allowed the UD team to validate that it is the plasmalogen lipids that keep the membranes fluid and deformable at high pressure.

“Using molecular-dynamic simulations to explore this system, we were able to test conditions that would be found even deeper in the sea than these ctenophore species actually live to see what happened,” said Vargas-Urbano.

This is because the deep-sea ctenophores contained more plasmalogen lipids in their cell membranes than other ctenophore species found at the sea surface and in the Arctic. In particular, the deep-dwelling ctenophores had higher concentrations of a plasmalogen known as PPE, which is characterized by a distinct cone shape. Simulations by the UD research team and artificial membrane experiments by Budin and Winnikoff showed the more PPE plasmalogen was present, the more the membranes curled up, even at low pressures.

One surprising result from the research, Lyman said, is that when they plotted the 17 ctenophore species studied, the researchers discovered a significant correlation between how much plasmalogen is found in the species’ cellular membrane and where it can live.

“If you take a deep-sea ctenophore and bring it to the surface, its membrane bends like crazy and that's no good. If you take a surface-dwelling ctenophore and bring it to the deep, its membrane won't bend anymore, also not good,” Lyman said.

But when the researchers compared the membrane of ctenophores living in surface waters and their deep-sea cousins in their natural environments, the species had similar properties in terms of how the molecules inside the cells adjust to keep the membrane stable.

The researchers called this effect “homeocurvature adaptation,” because the ctenophores—and their lipidomes—had adapted to the situation that they're living in. This understanding may help explain a long-standing mystery of why deep-sea invertebrates, including ctenophores, disintegrate at the surface no matter how carefully they are handled. It seems in some cases the membranes actually are held together by the extreme pressure.

Human health implications of the work

Knowing how life adapts to high pressure and extreme environments such as the ocean can also inform what is known about the human body. Lyman explained that plasmalogen lipids present in ctenophores also are found in our bodies, most abundantly in neural tissue.

“Nerve cells in the brain transmit messages by sending chemicals from one cell to another. And there is an awful lot of plasmalogen at the site where all that synaptic transmission is happening in your neurons,” said Lyman.

The loss of plasmalogen is known to be associated with conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, making new insights about the unique properties of plasmalogen lipids potentially useful in other areas of research.

Full list of authors: Daniel Milshteyn, Edward Dennis, Aaron Armando, Oswald Quehenberger and Itay Budin (all UC San Diego); Jacob Winnikoff (Harvard University); Sasiri J. Vargas-Urbano, Miguel Pedraza Joya and Edward Lyman (all University of Delaware); Alexander Sodt (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development); Richard E. Gillilan (Cornell University); and Steven H.D. Haddock (MBARI).

END

How well do deep-sea animals perform under pressure?

Research sheds new light on marine organisms' ability to adapt and survive in the ocean. It also may inform what’s known about the human body

2024-07-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

FDA staff leaving for industry jobs given “behind the scenes” lobbying advice

2024-07-02

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) tells staff leaving for industry jobs that, despite restrictions on post-employment lobbying, they are still permitted to influence the agency, reveals an investigation by The BMJ today.

Internal emails, obtained under a freedom of information request, show how two FDA officials who worked on covid-19 vaccine approvals were proactively informed by FDA ethics staff about their ability to indirectly lobby the agency as they left for jobs with Moderna.

The record shows that since 2000 every FDA commissioner, the agency’s highest position, has gone on to work ...

Herpes infections take major economic toll globally, new research shows

2024-07-02

Genital herpes infections and their related complications lead to billions of dollars in health care expenditures and productivity losses globally, according to the first ever global estimates of the economic costs of these conditions.

The paper, which publishes July 1st in the journal BMC Global and Public Health, calls for greater investment in prevention of herpes transmission, including concerted efforts to develop effective vaccines against this common virus.

Corresponding author Nathorn Chaiyakunapruk, PharmD, PhD, professor of pharmacotherapy, and Haeseon Lee, PharmD, research fellow in pharmacotherapy, both at the College of Pharmacy of University ...

Tax on antibiotics could help tackle threat of drug-resistance

2024-07-02

Taxing certain antibiotics could help efforts to tackle the escalating threat of antibiotic resistance in humans, according to a new study by the University of East Anglia’s Centre for Competition Policy, Loughborough University and E.CA Economics.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a significant global risk, causing an estimated 700,000 deaths annually. A key AMR report previously warned that if unchecked, it could endanger 10 million lives a year and result in $100 trillion in lost economic output ...

Organic material from Mars reveals the likely origin of life’s building blocks

2024-07-01

Organic material from Mars reveals the likely origin of life’s building blocks

Two samples from Mars together deliver the "smoking gun" in a new study showing the origin of Martian organic material. The study presents solid evidence for a prediction made over a decade ago by University of Copenhagen researchers that could be key to understanding how organic molecules, the foundation of life, were first formed here on Earth.

In a meteor crater on the red planet, a solitary robot is moving about. Right now it is probably collecting soil samples with a drill and a robotic arm, as it has quite ...

Light targets cells for death and triggers immune response with laser precision

2024-07-01

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A new method of precisely targeting troublesome cells for death using light could unlock new understanding of and treatments for cancer and inflammatory diseases, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign researchers report.

Inflammatory cell death, knows as necroptosis, is an important regulatory tool in the body’s arsenal against disease. However, in some diseases, the process can go haywire; for example, cancer cells are able to suppress inflammatory signals and thus escape death.

“Usually treatments for cancer use pharmacological ...

Dr. Harish Manyam revolutionizes cardiac care with innovative device

2024-07-01

Harish Manyam, MD, is on a mission to improve the lives of people with heart problems. His recent accomplishment of implanting Tennessee’s first atrial leadless pacemaker is a step toward that, marking a significant advancement in cardiac care and promising safer and more effective treatment for patients.

The leadless pacemaker, in combination with a novel subcutaneous defibrillator, forms a groundbreaking system that addresses potentially dangerous problems associated with traditional pacemakers and defibrillators.

“This is a great leap forward for the field,” said Dr. Manyam, interim chair of the Department of Medicine at the ...

Want to stay mentally sharp longer? Eat a healthy diet now

2024-07-01

Chicago (July 1, 2024) — Eating a high-quality diet in youth and middle age could help keep your brain functioning well in your senior years, according to new preliminary findings from a study that used data collected from over 3,000 people followed for nearly seven decades.

The research adds to a growing body of evidence that a healthy diet could help ward off Alzheimer’s disease and age-related cognitive decline. Whereas most previous research on the topic has focused on eating habits of people in their 60s and 70s, the new study is the first to track diet and ...

Medication choice may affect weight gain when initiating antidepressant treatment

2024-07-01

Embargoed for release until 5:00 p.m. ET on Monday 1 July 2024

Annals of Internal Medicine Tip Sheet

@Annalsofim

Below please find summaries of new articles that will be published in the next issue of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summaries are not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not only on their own behalf, but also on behalf of the organization ...

Weight change across common antidepressant medications

2024-07-01

Boston, MA – New evidence comparing weight gain under eight different first-line antidepressants finds that bupropion users are 15-20% less likely to gain a clinically significant amount of weight than users of sertraline, the most common medication.

The findings are published July 2 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Antidepressants are among the most commonly prescribed medications in the U.S., with 14% of U.S. adults reporting using an antidepressant. Weight gain is a common side effect, which could affect patients’ long-term metabolic health and cause some to stop taking their prescribed treatment, leading ...

Dampening the "seeds" of hurricanes

2024-07-01

Dampening the "seeds" of hurricanes

Increased atmospheric moisture produced weaker hurricane formation

Increased atmospheric moisture may alter critical weather patterns over Africa, making it more difficult for the predecessors of many Atlantic hurricanes to form, according to a new study published this month.

The research team, led by scientists from the U.S. National Science Foundation National Center for Atmospheric Research (NSF NCAR), used an innovative model that allows for higher-resolution simulations of hurricane formation than ever before. This allowed researchers to study the effects of increased regional moisture over Africa, which is the birthplace of ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New study calls for personalized, tiered approach to postpartum care

The hidden breath of cities: Why we need to look closer at public fountains

Rewetting peatlands could unlock more effective carbon removal using biochar

Microplastics discovered in prostate tumors

ACES marks 150 years of the Morrow Plots, our nation's oldest research field

Physicists open door to future, hyper-efficient ‘orbitronic’ devices

$80 million supports research into exceptional longevity

Why the planet doesn’t dry out together: scientists solve a global climate puzzle

Global greening: The Earth’s green wave is shifting

You don't need to be very altruistic to stop an epidemic

Signs on Stone Age objects: Precursor to written language dates back 40,000 years

MIT study reveals climatic fingerprints of wildfires and volcanic eruptions

A shift from the sandlot to the travel team for youth sports

Hair-width LEDs could replace lasers

The hidden infections that refuse to go away: how household practices can stop deadly diseases

Ochsner MD Anderson uses groundbreaking TIL therapy to treat advanced melanoma in adults

A heatshield for ‘never-wet’ surfaces: Rice engineering team repels even near-boiling water with low-cost, scalable coating

Skills from being a birder may change—and benefit—your brain

Waterloo researchers turning plastic waste into vinegar

Measuring the expansion of the universe with cosmic fireworks

How horses whinny: Whistling while singing

US newborn hepatitis B virus vaccination rates

When influencers raise a glass, young viewers want to join them

Exposure to alcohol-related social media content and desire to drink among young adults

Access to dialysis facilities in socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged communities

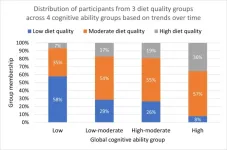

Dietary patterns and indicators of cognitive function

New study shows dry powder inhalers can improve patient outcomes and lower environmental impact

Plant hormone therapy could improve global food security

A new Johns Hopkins Medicine study finds sex and menopause-based differences in presentation of early Lyme disease

Students run ‘bee hotels’ across Canada - DNA reveals who’s checking in

[Press-News.org] How well do deep-sea animals perform under pressure?Research sheds new light on marine organisms' ability to adapt and survive in the ocean. It also may inform what’s known about the human body