(Press-News.org) Bowel cancer cells have the ability to regulate their growth using a genetic on-off switch to maximise their chances of survival, a phenomenon that’s been observed for the first time by researchers at UCL and University Medical Center Utrecht.

The number of genetic mutations in a cancer cell was previously thought to be purely down to chance. But a new study, published in Nature Genetics, has provided insights into how cancers navigate an “evolutionary balancing act”.

The researchers found that mutations in DNA repair genes can be repeatedly created and repaired, acting as ‘genetic switches’ that take the brakes off a tumour’s growth or put the brakes back on, depending on what would be most beneficial for the cancer to develop.

Researchers say the findings could potentially be used in personalised cancer medicine to gauge how aggressive an individual’s cancer is so that they can be given the most effective treatment.

Cancer is a genetic disease caused by mutations in our DNA. DNA damage occurs throughout life, both naturally and due to environmental factors. To cope with this, cells have evolved strategies to protect the integrity of the genetic code, but if mutations accumulate in key genes linked to cancer, tumours can develop.

Bowel cancer is the fourth most common cancer in the UK, with around 42,900 cases a year. Though still predominantly a cancer that affects older people, cases among the under 50s have been increasing in recent decades.

Disruption of DNA repair mechanisms is a major cause of increased cancer risk. About 20% of bowel cancers, known as mismatch repair deficient (MMRd) cancers, are caused by mutations in DNA repair genes. But disrupting these repair mechanisms is not entirely beneficial to tumours. Though they do allow tumours to develop, each mutation increases the risk that the body’s immune system will be triggered to attack the tumour.

Dr Marnix Jansen, senior author of the study from UCL Cancer Institute and UCLH, said: “Cancer cells need to acquire certain mutations to circumvent mechanisms that preserve our genetic code. But if a cancer cell acquires too many mutations, it is more likely to attract the attention of the immune system, because it’s so different from a normal cell.

“We predicted that understanding how tumours exploit faulty DNA repair to drive tumour growth – whilst simultaneously avoiding immune detection – might help explain why the immune system sometimes fails to control cancer development.”

In this study, researchers from UCL analysed whole genome sequences from 217 MMRd bowel cancer samples in the 100,000 Genomes Project database. They looked for links between the total number of mutations and genetic changes in key DNA repair genes.

The team identified a strong correlation between DNA repair mutations in the MSH3 and MSH6 genes, and an overall high volume of mutations.

The theory that these ‘flip-flop’ mutations in DNA repair genes might control cancer mutation rates was then validated in complex cell models, called organoids, grown in the lab from patient tumour samples.

Dr Suzanne van der Horst from University Medical Center Utrecht said: “Our study reveals that DNA repair mutations in the MSH3 and MSH6 genes act as a genetic switch that cancers exploit to navigate an evolutionary balancing act. On one hand, these tumours roll the dice by turning off DNA repair to escape the body’s defence mechanisms. While this unrestrained mutation rate kills many cancer cells, it also produces a few ‘winners’ that fuel tumour development.

“The really interesting finding from our research is what happens afterwards. It seems the cancer turns the DNA repair switch back on to protect the parts of the genome that they too need to survive and to avoid attracting the attention of the immune system. This is the first time that we’ve seen a mutation that can be created and repaired over and over again, adding it or deleting it from the cancer’s genetic code as required.”

The DNA repair mutations in question occur in repetitive stretches of DNA found throughout the human genome, where one individual DNA letter (an A, T, C or G) is repeated many times. Cells often make small copying mistakes in these repetitive stretches during cell division, such as changing eight Cs into seven Cs, which disrupts gene function.

Dr Hamzeh Kayhanian, first author of the study from UCL Cancer Institute and UCLH, said: “The degree of genetic disarray in a cancer was previously thought to be purely down to chance accumulation of mutations over many years. Our work shows that cancer cells covertly repurpose these repetitive tracts in our DNA as evolutionary switches to fine-tune how rapidly mutations accumulate in tumour cells.

“Interestingly, this evolutionary mechanism had previously been found as a key driver of bacterial treatment resistance in patients treated with antibiotics. Like cancer cells, bacteria have evolved genetic switches which increase mutational fuel when rapid evolution is key, for example when confronted with antibiotics. Our work thus further emphasises similarities between evolution of ancient bacteria and human tumour cells, a major area of active cancer research.”

The researchers say that this knowledge could potentially be used to gauge the characteristics of a patient’s tumour, which may require more intense treatment if DNA repair has been switched off and there is potential for the tumour to adapt more quickly to evade treatment – particularly to immunotherapies, which are designed to target heavily mutated tumours.

A follow-up study is already underway to find out what happens to these DNA repair switches in patients who receive cancer treatment.

Dr Hugo Snippert, a senior author of the study from University Medical Center Utrecht, said: “Overall our research shows that mutation rate is adaptable in tumours and facilitates their quest to obtain optimal evolutionary fitness. New drugs might look to disable this switch to drive effective immune recognition and, hopefully, produce better treatment outcomes for affected patients.”

This research was funded with grants from Cancer Research UK, the Rosetrees Trust, and Bowel Research UK.

Georgia Sturt, Research and Grants Manager at Bowel Research UK, said: “Cancer’s evasion of immune system destruction is a key element of its ability to grow and spread. Understanding exactly how bowel cancers do this is crucial to optimising treatment for patients. Bowel Research UK are delighted that our funding has contributed to producing this exciting new data, and we look forward to seeing how these discoveries could change treatments for future patients."

END

Bowel cancer turns genetic switches on and off to outwit the immune system

2024-07-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Shark hatching success drops from 82% to 11% in climate change scenario

2024-07-03

New experimental research shows that the combined effects of ocean warming and acidification could lead to a catastrophic decrease in embryonic shark survival by the year 2100. This research is also the first to demonstrate that monthly temperature variation plays a prominent role in shark embryo mortality.

Oceanic warming and acidification are caused by greater concentrations of CO2 dissolving into marine environments, resulting in rising water temperatures and falling pH levels. “The embryos of egg-laying ...

Meet the team 3D modelling France’s natural history collections

2024-07-03

France’s natural history collections contain nearly 6% of the world’s total natural specimens across multiple institutions, and the e-COL+ project aims to capture and reconstruct these specimens in 3D for easy access and 3D printing around the world.

“I’m a researcher of vertebrate locomotion and vocalisation, so I produce a lot of CT scans and 3D models – and now I’m in charge of developing the museum’s own 3D digital collection,” ...

Artificial light is a deadly siren song for young fish

2024-07-03

New research finds that artificial light at night (ALAN) attracts larval fish away from naturally lit habitats, while dramatically lowering their chances of survival in an “ecological trap”, with serious consequences for fish conservation and fishing stock management.

“Light pollution is a huge ongoing subject with many aspects that are still not well understood by scientists,” says Mr Jules Schligler, a PhD student at CRIOBE Laboratory (Centre de Recherches Insulaires et Observatoire de l’Environnement) in Moorea, French Polynesia.

ALAN is the product of human-related ...

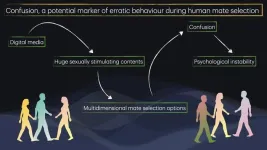

Social media is a likely cause of ‘confusion’ in modern mate selection

2024-07-03

A recent sociological study finds that most young adults surveyed reported feeling confused about their options when it comes to dating decisions. Preliminary analysis suggests that more than half of young people experience confusion about choosing life-partners, with women appearing to be more likely to report partner selection confusion than men.

Due to the pervasiveness of social media and digital dating in everyday lives, humans are now exposed to many more potential mates than ever before, but the availability of popular dating apps ...

Exploring bird breeding behaviour and microbiomes in the radioactive Chornobyl Exclusion Zone

2024-07-03

New research finds surprising differences in the diets and gut microbiomes of songbirds living in the radiation contaminated areas of the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone, Ukraine. This study is also the first to examine the breeding behaviour and early life of birds growing up in radiologically contaminated habitats.

The Chornobyl Exclusion Zone (Ukrainian), also known as the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (Russian), is an area of approximately 2,600 km2 of radiologically contaminated land that surrounds the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant. The levels of contamination are uneven throughout the zone.

“The ...

Discovering new anti-aging secrets from the world’s longest-living vertebrate

2024-07-03

New experimental research shows that muscle metabolic activity may be an important factor in the incredible longevity of the world’s oldest living vertebrate species – the Greenland shark. These findings may have applications for conservation of this vulnerable species against climate change or even for human cardiovascular health.

Greenland sharks (Somniosus microcephalus) are the longest living vertebrate with an expected lifespan of at least 270 years and possible lifespan beyond 500 years. “We want to understand what adaptations ...

Pregnant fish can also get “baby brain”, but not the way that mammals do

2024-07-03

New research reveals that pregnancy-related brain impairment is present in live-bearing fish, but instead of affecting learning and memory as expected from similar research on mammals, it appears to have a stronger impact on decision-making and sensory reception.

There have been many studies into the detrimental impact of pregnancy on mammalian brains, sometimes called “baby brain” or “momnesia” in humans, revealing how the disruption of neurological processes like neurogenesis, or the creation ...

Pasteurization inactivates highly infectious avian flu in milk

2024-07-03

Highlights:

• In late March 2024, H5N1 bird flu was detected in dairy cattle and then in raw milk.

• Researchers tested hundreds of milk products from dozens of states for the virus.

• No infectious virus was found in pasteurized milk products.

• Non-infectious traces of viral genetic material were found in 20% of samples.

Washington, D.C.—In March 2024, dairy cows in Texas were found to be infected with highly pathogenic avian flu, ...

KIER develops 'viologen redox flow battery' to replace vanadium’

2024-07-03

A technology has been developed to replace the active material in large-capacity ESS 'redox flow batteries' with a more affordable substance.

*Redox Flow Battery: A term synthesized from Reduction, Oxidation, and Flow. It is a battery that stores electrical energy as chemical energy through oxidation and reduction reactions of active materials in the electrolyte at the electrode surface and converts it back to electrical energy when needed. It is capable of large-scale storage, can be used long-term through periodic replacement of the electrolyte, and its major advantage is the absence of fire risk.

Dr. Seunghae Hwang’s ...

Chemists synthesize an improved building block for medicines

2024-07-03

Chemists have overcome a major hurdle in synthesizing a more stable form of heterocycle—a family of organic compounds that are a common component of most modern pharmaceuticals.

The research, which could expand the toolkit available to drug developers in improving the safety profiles of medications and reducing side effects, was published in Science by organic chemists at the University of British Columbia (UBC), the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and the University of Michigan.

“Azetidines ...