(Press-News.org) Bone remains found in a Tibetan cave 3,280 m above sea level indicate an ancient group of humans survived here for many millennia, according to a new study published in Nature.

The Denisovans are an extinct species of ancient human that lived at the same time and in the same places as Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. Only a handful Denisovan remains have ever been discovered by archaeologists. Little is known about the group, including when they became extinct, but evidence exists to suggest they interbred with both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens.

A research team led by Lanzhou University, China, the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, CAS, China, and involving the University of Reading studied more than 2,500 bones from the Baishiya Karst Cave on the high-altitude Tibetan Plateau, one of the only two places where Denisovans are known to have lived.

Their new analysis, published today (Wednesday, 3 July) in Nature, has identified a new Denisovan fossil and shed light on the species’ ability to survive in fluctuating climatic conditions — including the ice age — on the Tibetan plateau from around 200,000 to 40,000 years ago.

Dr Geoff Smith, a zooarchaeologist at the University of Reading, is a co-author of the study. He said: “We were able to identify that Denisovans hunted, butchered and ate a range of animal species. Our study reveals new information about the behaviour and adaptation of Denisovans both to high altitude conditions and shifting climates. We are only just beginning to understand the behaviour of this extraordinary human species.”

Dietary diversity

Bone remains from Baishya Karst Cave were broken into numerous fragments preventing identification. The team used a novel scientific method that exploits differences in bone collagen between animals to determine which species the bone remains came from.

Dr Huan Xia, of Lanzhou University, said: “Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS) allows us to extract valuable information from often overlooked bone fragments, providing deeper insight into human activities.”

The research team determined that most of the bones were from blue sheep, known as the bharal, as well as wild yaks, equids, the extinct woolly rhino, and the spotted hyena. The researchers also identified bone fragments from small mammals, such as marmots, and birds.

Dr Jian Wang, of Lanzhou University, said: “Current evidence suggests that it was Denisovans, not any other human groups, who occupied the cave and made efficient use of all the animal resources available to them throughout their occupation.”

Detailed analysis of the fragmented bone surfaces shows the Denisovans removed meat and bone marrow from the bones, but also indicate the humans used them as raw material to produce tools.

A new Denisovan fossil

The scientists also identified one rib bone as belonging to a new Denisovan individual. The layer where the rib was found was dated to between 48,000 and 32,000 years ago, implying that this Denisovan individual lived at a time when modern humans were dispersing across the Eurasian continent. The results indicate that Denisovans lived through two cold periods, but also during a warmer interglacial period between the Middle and Late Pleistocene eras.

Dr Frido Welker, of the University of Copenhagen, said: “Together, the fossil and molecular evidence indicates that Ganjia Basin, where Baishiya Karst Cave is located, provided a relatively stable environment for Denisovans, despite its high-altitude.

"The question now arises when and why these Denisovans on the Tibetan Plateau went extinct.”

END

Extinct humans survived on the Tibetan plateau for 160,000 years

2024-07-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

PolyU study reveals the mechanism of bio-inspired control of liquid flow, enlightening breakthroughs in fluid dynamics and nature-inspired materials technologies

2024-07-03

The more we discover about the natural world, the more we find that nature is the greatest engineer. Past research believed that liquids can only be transported in fixed direction on species with specific liquid communication properties and cannot switch the transport direction. Recently, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU) researchers have shown that an African plant controls water movement in a previously unknown way – and this could inspire breakthroughs in a range of technologies in fluid dynamics and nature-inspired materials, including applications that require multistep and repeated reactions, such as microassays, medical ...

Early-onset El Niño means warmer winters in East Asia, and vice versa

2024-07-03

Fukuoka, Japan—The phenomenon known as El Niño can cause abnormal and extreme climate around the world due to it dramatically altering the normal flow of the atmosphere. In Japan, historical data has shown that El Niño years tend to lead to warmer winters. This case was exemplified recently with Japan’s warm 2023-2024 winter season. However, there have also been cases of cold winters in Japan during El Niño years, such as the one recorded in 2014-2015. Yet, it was unclear as to why this was occurring.

Publishing in the Journal of Climate, ...

How to avoid wasting huge amounts of energy

2024-07-03

Norway wastes huge amounts of energy. Surplus heat produced by industry is hardly exploited at all.

Researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) have been looking at the possibilities for doing something about this.

“Surplus heat from industrial processes is a huge resource,” says Kim Kristiansen.

He has just completed his PhD on a technology that can harness some of the surplus heat that currently goes to waste. Almost all the heat generated by industrial processes is currently released directly into the air or the ocean, and we are not talking about small amounts. In Norway alone, industry produces ...

Bowel cancer turns genetic switches on and off to outwit the immune system

2024-07-03

Bowel cancer cells have the ability to regulate their growth using a genetic on-off switch to maximise their chances of survival, a phenomenon that’s been observed for the first time by researchers at UCL and University Medical Center Utrecht.

The number of genetic mutations in a cancer cell was previously thought to be purely down to chance. But a new study, published in Nature Genetics, has provided insights into how cancers navigate an “evolutionary balancing act”.

The researchers found that mutations in DNA repair genes can be repeatedly created and repaired, acting as ‘genetic switches’ that take the brakes off a tumour’s growth ...

Shark hatching success drops from 82% to 11% in climate change scenario

2024-07-03

New experimental research shows that the combined effects of ocean warming and acidification could lead to a catastrophic decrease in embryonic shark survival by the year 2100. This research is also the first to demonstrate that monthly temperature variation plays a prominent role in shark embryo mortality.

Oceanic warming and acidification are caused by greater concentrations of CO2 dissolving into marine environments, resulting in rising water temperatures and falling pH levels. “The embryos of egg-laying ...

Meet the team 3D modelling France’s natural history collections

2024-07-03

France’s natural history collections contain nearly 6% of the world’s total natural specimens across multiple institutions, and the e-COL+ project aims to capture and reconstruct these specimens in 3D for easy access and 3D printing around the world.

“I’m a researcher of vertebrate locomotion and vocalisation, so I produce a lot of CT scans and 3D models – and now I’m in charge of developing the museum’s own 3D digital collection,” ...

Artificial light is a deadly siren song for young fish

2024-07-03

New research finds that artificial light at night (ALAN) attracts larval fish away from naturally lit habitats, while dramatically lowering their chances of survival in an “ecological trap”, with serious consequences for fish conservation and fishing stock management.

“Light pollution is a huge ongoing subject with many aspects that are still not well understood by scientists,” says Mr Jules Schligler, a PhD student at CRIOBE Laboratory (Centre de Recherches Insulaires et Observatoire de l’Environnement) in Moorea, French Polynesia.

ALAN is the product of human-related ...

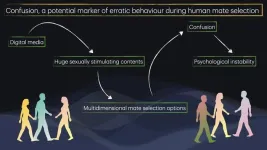

Social media is a likely cause of ‘confusion’ in modern mate selection

2024-07-03

A recent sociological study finds that most young adults surveyed reported feeling confused about their options when it comes to dating decisions. Preliminary analysis suggests that more than half of young people experience confusion about choosing life-partners, with women appearing to be more likely to report partner selection confusion than men.

Due to the pervasiveness of social media and digital dating in everyday lives, humans are now exposed to many more potential mates than ever before, but the availability of popular dating apps ...

Exploring bird breeding behaviour and microbiomes in the radioactive Chornobyl Exclusion Zone

2024-07-03

New research finds surprising differences in the diets and gut microbiomes of songbirds living in the radiation contaminated areas of the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone, Ukraine. This study is also the first to examine the breeding behaviour and early life of birds growing up in radiologically contaminated habitats.

The Chornobyl Exclusion Zone (Ukrainian), also known as the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (Russian), is an area of approximately 2,600 km2 of radiologically contaminated land that surrounds the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant. The levels of contamination are uneven throughout the zone.

“The ...

Discovering new anti-aging secrets from the world’s longest-living vertebrate

2024-07-03

New experimental research shows that muscle metabolic activity may be an important factor in the incredible longevity of the world’s oldest living vertebrate species – the Greenland shark. These findings may have applications for conservation of this vulnerable species against climate change or even for human cardiovascular health.

Greenland sharks (Somniosus microcephalus) are the longest living vertebrate with an expected lifespan of at least 270 years and possible lifespan beyond 500 years. “We want to understand what adaptations ...