(Press-News.org) The complexity of the melodies of the most popular songs each year in the USA — according to the Billboard year-end singles charts — has decreased since 1950, a study published in Scientific Reports suggests.

Madeline Hamilton and Marcus Pearce analysed the most prominent melodies (usually the vocal melody) of songs that reached the top five positions of the US Billboard year-end singles music charts each year between 1950 and 2022. They found that the complexity of song rhythms and pitch arrangements decreased over this period as the average number of notes played per second increased. They also identified two significant decreases in melodic complexity that occurred in 1975 and 2000, along with a smaller decrease in 1996. The authors speculate that the melodic changes that occurred in 1975 could represent the rise of genres such as new wave, disco and stadium rock. Those occurring in 1996 and 2000 could represent the rise of hip-hop or the adoption of digital audio workstations, which enabled the repeated playing of audio loops, they add.

The authors note that although the complexity of popular melodies appears to have decreased in recent decades, this does not suggest that the complexity of other musical components — such as the quality or combinations of sounds — has also decreased. They speculate that decreases in melodic complexity could result from increases in the complexity of other musical elements, such as an increase in the average number of notes played per second, to prevent music from sounding overwhelming to listeners. Additionally, they propose that expansions in the availability of digital instruments may enable musical complexity to be expressed through sound quality, rather than melody.

The findings provide further insight into the evolution of popular music over the past 70 years.

###

Article details

Trajectories and revolutions in popular melody based on U.S. charts from 1950 to 2023

DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-64571-x

Corresponding Author:

Madeline Hamilton

Queen Mary University of London, London, UK

Email: m.a.hamilton@qmul.ac.uk

END

Music: Song melodies have become simpler since 1950

2024-07-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Effects of visual and auditory instructions on space station procedural tasks

2024-07-04

Firstly, the authors provided a detailed explanation of the experimental methods and procedures. This study recruited 30 healthy subjects (15 males and 15 females), aged between 20 to 50 years, with an average age of 42 ± 6.58 years. All participants had no severe visual or auditory impairments and were right-handed. The subjects met the biometric standards for astronaut candidates and were rigorously screened. The experiment used Unity 3D to model the space station, simulating the internal scenes of the space station. The subjects started from the core node module and found the laboratory module I, where they operated the Space Raman Spectrometer ...

Norway can lead the fight against plastic pollution

2024-07-04

Plastic items from around the world are continuously washing ashore on Norwegian coastlines. This reflects a much larger systemic issue facing the nations of the world.

Scientists have long reported the consequences of plastic pollution and the urgent need for intervention, but global plastic production and consumption continue to rise.

This underscores the importance of Norway’s advocacy for a global agreement that guarantees stopping the flow of plastics into the environment.

But Norway also has a responsibility in generating plastic pollution.

In a study conducted ...

Decolonizing the Tropical Ecology curriculum

2024-07-04

A new study of curriculum reading material at the University of Glasgow finds that 94% of recommended Tropical Ecology authors are white, and that 80% of authors are affiliated with universities outside of the tropics. Dr Stewart White, Senior Lecturer at the School of Biodiversity, One Health and Veterinary Medicine at the University of Glasgow, UK, intends to change that.

“Tropical rainforest research was long the preserve of rich white men and the resulting literature was the same,” says Dr White. “This historical bias in tropical research and publication is still ...

Exploring the casque anatomy of aerial jousting helmeted hornbills

2024-07-04

New research reveals how the surprising internal anatomy of the helmeted hornbill’s casque allows it to withstand damage during aerial jousting battles with rivals. Researchers hope that this new understanding can help to conserve this critically endangered species, as well as provide new insights into developing impact-resistant bio-mimetic materials.

“When I started in Hong Kong, I visited City University of Hong Kong (HKU)’s conservation forensics group to chat about their research and they introduced me to this amazing bird, to its ...

A New Blue: Mysterious origin of the ribbontail ray’s electric blue spots revealed

2024-07-04

Researchers have discovered the unique nanostructures responsible for the electric blue spots of the bluespotted ribbontail ray (Taeniura lymma), with possible applications for developing chemical-free colouration. The team are also conducting ongoing research into the equally enigmatic blue colouration of the blue shark (Prionace glauca).

Skin colouration plays a key role in organismal communication, providing life-critical visual clues that can warn, attract or camouflage. Bluespotted ribbontail ...

Cool roofs are best at beating cities’ heat

2024-07-04

Painting roofs white or covering them with a reflective coating would be more effective at cooling cities like London than vegetation-covered “green roofs,” street-level vegetation or solar panels, finds a new study led by UCL researchers.

Conversely, extensive use of air conditioning would warm the outside environment by as much as 1 degree C in London’s dense city centre, the researchers found.

The research, published in Geophysical Research Letters, used a three-dimensional urban climate model of Greater London to test the thermal effects of different passive and active urban heat management systems, including painted “cool roofs,” rooftop solar panels, ...

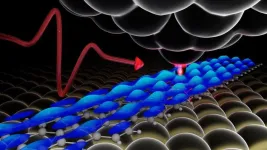

Single atoms show their true color

2024-07-04

One of the challenges of cramming smarter and more powerful electronics into ever-shrinking devices is developing the tools and techniques to analyze the materials that make them up with increasingly intimate precision.

Physicists at Michigan State University have taken a long-awaited step on that front with an approach that combines high-resolution microscopy with ultrafast lasers.

The technique, described in the journal Nature Photonics, enables researchers to spot misfit atoms in semiconductors with unparalleled precision. Semiconductor physics labels these atoms as “defects,” which sounds negative, but they’re ...

Re-engineering cancerous tumors to self-destruct and kill drug-resistant cells

2024-07-04

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Treating cancer can sometimes feel like a game of Whac-A-Mole. The disease can become resistant to treatment, and clinicians never know when, where and what resistance might emerge, leaving them one step behind. But a team led by Penn State researchers has found a way to reprogram disease evolution and design tumors that are easier to treat.

They created a modular genetic circuit that turns cancer cells into a “Trojan horse,” causing them to self-destruct and kill nearby drug-resistant ...

Reversing chemotherapy resistance in pancreatic cancer

2024-07-04

Pancreatic cancer is a particularly aggressive and difficult-to-treat cancer, in part because it is often resistant to chemotherapy. Now, researchers at Stanford have revealed that this resistance is related to both the physical stiffness of the tissue around the cancerous cells and the chemical makeup of that tissue. Their work, published on July 4 in Nature Materials, shows that this resistance can be reversed and reveals potential targets for new pancreatic cancer treatments.

“We found that stiffer tissue can cause pancreatic cancer cells to become resistant to chemotherapy, while softer tissue made ...

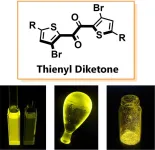

New organic molecule shatters phosphorescence efficiency records and paves way for rare metal-free applications

2024-07-04

A research team led by Osaka University discovered that the new organic molecule thienyl diketone shows high-efficiency phosphorescence. It achieved phosphorescence that is more than ten times faster than traditional materials, allowing the team to elucidate this mechanism.

Osaka, Japan – Phosphorescence is a valuable optical function used in applications such as organic EL displays (OLEDs) and cancer diagnostics. Until now, achieving high-efficiency phosphorescence without using rare metals such as iridium and platinum has been a significant challenge. Phosphorescence, which occurs when a molecule transitions ...