(Press-News.org) Curious bits of DNA tucked inside genomes across all kingdoms of life historically have been disregarded since they don’t seem to have a role to play in the competition for survival. Or so researchers thought.

These DNA pieces came to be known as “selfish genetic elements” because they exist, as far as scientists could tell, to simply reproduce and propagate themselves, without any benefit to their host organisms. They were seen as genetic hitchhikers that have been inconsequentially passed from one generation to the next.

Research conducted by scientists at the University of California San Diego has provided fresh evidence that such DNA elements might not be so selfish after all. Instead, they now appear to factor considerably into the dynamics between competing organisms.

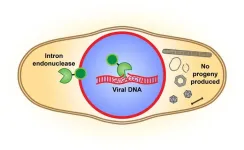

Publishing in the journal Science, researchers in the School of Biological Sciences studied selfish genetic elements in bacteriophages (phages), viruses that are considered the most abundant organisms on Earth. To their surprise, researchers found that selfish genetic elements known as “mobile introns” provide their virus hosts with a clear advantage when competing with other viruses: phages have weaponized mobile introns to disrupt the ability of competing phage viruses to reproduce.

“This is the first time a selfish genetic element has been demonstrated to confer a competitive advantage to the host organism it has invaded,” said study co-first author Erica Birkholz, a postdoctoral scholar in the Department of Molecular Biology. “Understanding that selfish genetic elements are not always purely ‘selfish’ has wide implications for better understanding the evolution of genomes in all kingdoms of life.”

Decades ago biologists noted the existence of selfish genetic elements but were unable to characterize any role they play in helping the host organism survive and reproduce. In the new study, which focused on investigating “jumbo” phages, the researchers analyzed the dynamics as two phages co-infect a single bacterial cell and compete against each other.

They looked closely at the endonuclease, an enzyme that serves as a DNA cutting tool. The endonuclease from one phage’s mobile intron, the studies showed, interferes with the genome of the competing phage. The endonuclease therefore is now regarded as a combat tool since it has been documented cutting an essential gene in the competing phage’s genome. This sabotages the competitor’s ability to appropriately assemble its own progeny and reproduce.

“This weaponized intron endonuclease gives a competitive advantage to the phage carrying it,” said Birkholz.

The researchers say the finding is especially important in the evolutionary arms race between viruses due to the constant competition in co-infection.

“We were able to clearly delineate the mechanism that gives an advantage and how that happens at the molecular level,” said Biological Sciences graduate student Chase Morgan, the paper’s co-first author. “This incompatibility between selfish genetic elements becomes molecular warfare.”

The results of the study are important as phage viruses emerge as therapeutic tools in the fight against antibiotic resistant bacteria. Since doctors have been deploying “cocktails” of phage to combat infections in this growing crisis, the new information is likely to come into play when multiple phage are implemented. Knowing that certain phage are using selfish genetic elements as weapons against other phage could help researchers understand why certain combinations of phage may not reach their full therapeutic potential.

“The phages in this study can be used to treat patients with bacterial infections associated with cystic fibrosis,” said Biological Sciences Professor Joe Pogliano. “Understanding how they compete with one another will allow us to make better cocktails for phage therapy.”

The authors of the paper are: Erica Birkholz, Chase Morgan, Thomas Laughlin, Rebecca Lau, Amy Prichard, Sahana Rangarajan, Gabrielle Meza, Jina Lee, Emily Armbruster, Sergey Suslov, Kit Pogliano, Justin Meyer, Elizabeth Villa, Kevin Corbett and Joe Pogliano.

The research detailed in the Science study was funded by an Emerging Pathogens Initiative grant from the Howard Hughes Medical institute, the National Institutes of Health (R01- GM129245 and R35 GM144121) and the National Science Foundation (MRI grant NSF DBI 1920374).

Competing interest disclosure: Professors Kit and Joe Pogliano have an equity interest in Linnaeus Bioscience Inc. and receive income.

END

Not so selfish after all: Viruses use freeloading genes as weapons

Phage viruses, which are increasingly used to treat antibiotic resistance, gain an advantage by cutting off a competitor’s ability to reproduce

2024-07-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers identify unknown signalling pathway in the brain responsible for migraine with aura

2024-07-04

A previously unknown mechanism by which proteins from the brain are carried to a particular group of sensory nerves causes migraine attacks, a new study shows. This may pave the way for new treatments for migraine and other types of headaches.

More than 800,000 Danes suffer from migraines – a condition characterised by severe headache in one side of the head. In around a fourth of all migraine patients, headache attacks are preceded by aura – symptoms from the brain such as temporary visual or sensory disturbances preceding the migraine attack by 5-60 minutes.

While ...

Music: Song melodies have become simpler since 1950

2024-07-04

The complexity of the melodies of the most popular songs each year in the USA — according to the Billboard year-end singles charts — has decreased since 1950, a study published in Scientific Reports suggests.

Madeline Hamilton and Marcus Pearce analysed the most prominent melodies (usually the vocal melody) of songs that reached the top five positions of the US Billboard year-end singles music charts each year between 1950 and 2022. They found that the complexity of song rhythms and pitch arrangements decreased over this period as the average number of notes ...

Effects of visual and auditory instructions on space station procedural tasks

2024-07-04

Firstly, the authors provided a detailed explanation of the experimental methods and procedures. This study recruited 30 healthy subjects (15 males and 15 females), aged between 20 to 50 years, with an average age of 42 ± 6.58 years. All participants had no severe visual or auditory impairments and were right-handed. The subjects met the biometric standards for astronaut candidates and were rigorously screened. The experiment used Unity 3D to model the space station, simulating the internal scenes of the space station. The subjects started from the core node module and found the laboratory module I, where they operated the Space Raman Spectrometer ...

Norway can lead the fight against plastic pollution

2024-07-04

Plastic items from around the world are continuously washing ashore on Norwegian coastlines. This reflects a much larger systemic issue facing the nations of the world.

Scientists have long reported the consequences of plastic pollution and the urgent need for intervention, but global plastic production and consumption continue to rise.

This underscores the importance of Norway’s advocacy for a global agreement that guarantees stopping the flow of plastics into the environment.

But Norway also has a responsibility in generating plastic pollution.

In a study conducted ...

Decolonizing the Tropical Ecology curriculum

2024-07-04

A new study of curriculum reading material at the University of Glasgow finds that 94% of recommended Tropical Ecology authors are white, and that 80% of authors are affiliated with universities outside of the tropics. Dr Stewart White, Senior Lecturer at the School of Biodiversity, One Health and Veterinary Medicine at the University of Glasgow, UK, intends to change that.

“Tropical rainforest research was long the preserve of rich white men and the resulting literature was the same,” says Dr White. “This historical bias in tropical research and publication is still ...

Exploring the casque anatomy of aerial jousting helmeted hornbills

2024-07-04

New research reveals how the surprising internal anatomy of the helmeted hornbill’s casque allows it to withstand damage during aerial jousting battles with rivals. Researchers hope that this new understanding can help to conserve this critically endangered species, as well as provide new insights into developing impact-resistant bio-mimetic materials.

“When I started in Hong Kong, I visited City University of Hong Kong (HKU)’s conservation forensics group to chat about their research and they introduced me to this amazing bird, to its ...

A New Blue: Mysterious origin of the ribbontail ray’s electric blue spots revealed

2024-07-04

Researchers have discovered the unique nanostructures responsible for the electric blue spots of the bluespotted ribbontail ray (Taeniura lymma), with possible applications for developing chemical-free colouration. The team are also conducting ongoing research into the equally enigmatic blue colouration of the blue shark (Prionace glauca).

Skin colouration plays a key role in organismal communication, providing life-critical visual clues that can warn, attract or camouflage. Bluespotted ribbontail ...

Cool roofs are best at beating cities’ heat

2024-07-04

Painting roofs white or covering them with a reflective coating would be more effective at cooling cities like London than vegetation-covered “green roofs,” street-level vegetation or solar panels, finds a new study led by UCL researchers.

Conversely, extensive use of air conditioning would warm the outside environment by as much as 1 degree C in London’s dense city centre, the researchers found.

The research, published in Geophysical Research Letters, used a three-dimensional urban climate model of Greater London to test the thermal effects of different passive and active urban heat management systems, including painted “cool roofs,” rooftop solar panels, ...

Single atoms show their true color

2024-07-04

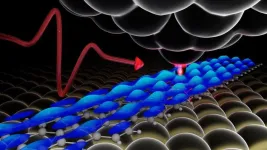

One of the challenges of cramming smarter and more powerful electronics into ever-shrinking devices is developing the tools and techniques to analyze the materials that make them up with increasingly intimate precision.

Physicists at Michigan State University have taken a long-awaited step on that front with an approach that combines high-resolution microscopy with ultrafast lasers.

The technique, described in the journal Nature Photonics, enables researchers to spot misfit atoms in semiconductors with unparalleled precision. Semiconductor physics labels these atoms as “defects,” which sounds negative, but they’re ...

Re-engineering cancerous tumors to self-destruct and kill drug-resistant cells

2024-07-04

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Treating cancer can sometimes feel like a game of Whac-A-Mole. The disease can become resistant to treatment, and clinicians never know when, where and what resistance might emerge, leaving them one step behind. But a team led by Penn State researchers has found a way to reprogram disease evolution and design tumors that are easier to treat.

They created a modular genetic circuit that turns cancer cells into a “Trojan horse,” causing them to self-destruct and kill nearby drug-resistant ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

[Press-News.org] Not so selfish after all: Viruses use freeloading genes as weaponsPhage viruses, which are increasingly used to treat antibiotic resistance, gain an advantage by cutting off a competitor’s ability to reproduce