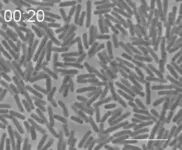

(Press-News.org) Dense E.coli bacteria have several similar qualities to colloidal glass, according to new research at the University of Tokyo. Colloids are substances made up of small particles suspended within a fluid, like ink for example. When these particles become higher in density and more packed together, they form a “glassy state.” When researchers multiplied E.coli bacteria within a confined area, they found that they exhibited similar characteristics. More surprisingly, they also showed some other unique properties not typically found in glass-state materials. This study contributes to our understanding of glassy “active matter,” a relatively new field of materials research which crosses physics and life science. In the long term, the researchers hope that these results will contribute to developing materials with new functional capabilities, as well as aiding our understanding of biofilms (where microorganisms stick together to form layers on surfaces) and natural bacterial colonies.

What do butter, soap and ink all have in common? They certainly don’t all taste good, but they are all types of colloids, substances made of particles suspended in fluid. When the concentration of particles is low, then the substance will be more liquid, and when it is high, then it becomes more solid (think of a dried-out inkwell). When this happens, the substance enters a glassy state, whereby the movement of the particles is restricted. However, although it may feel hard, unlike with other solids, the particles do not form fixed patterns but are jumbled together randomly. This is similar to the molecular structure of glass.

Researchers have now found that the bacteria E. Coli can behave in a similar way. “Since bacteria are very different from what we know of as glass, it was surprising that many of the statistical properties of glassy materials were the same for bacteria,” said Associate Professor Kazumasa Takeuchi from the Department of Physics at the Graduate School of Science. “However, the bigger surprise for us was that in-depth analysis revealed not only a similarity to the standard properties of glass, but also other properties beyond that. Our results call for an extension of our current understanding of the physics of glass.”

Takeuchi was inspired to carry out the experiment after observing the behavior of bacteria in a different study over 10 years ago. At that time, he saw that when a population of bacteria became very dense, it abruptly stopped moving and he wanted to understand why.

The main challenge was to create an environment in which the bacteria could equally thrive and multiply to form a dense population. To achieve this, the team used a device they had previously developed, which enabled them to equally distribute nutrients through a porous membrane to all the bacteria. The researchers then observed the bacteria by microscope over 5-6 hours.

As the number of E.coli increased, they became caged in by their neighbors, restricting their ability to swim freely. Over time, they transitioned to a glassy state. This transition is similar to glass formation, as the researchers noted a rapid slowdown of movement, the caged-in effect and dynamic heterogeneity (whereby molecules travel longer distances in some areas but hardly move in others).

What made this bacterial glass different to other glasslike substances was the spontaneous formation of “microdomains” and the collective motion of the bacteria within these areas. These occurred where groups of the rod-shaped E.coli became aligned the same way. The researchers were also surprised that the way the bacteria vitrify (turn into a glasslike state) apparently violates a physical law of typical thermal systems. What we characteristically know as glass, including colloidal glass, is classed as thermal glass. However, recently researchers have started to explore glassy states, like the one reported in this paper, which aren’t considered thermal glass but share many of the same properties.

“Collections of ‘self-propelled particles’ like we see here have recently been regarded as a new kind of material called active matter, which is currently a hot topic and shows great potential,” explained Takeuchi. “Our results on bacterial glass are along this line of research, extending this concept to the realm of glassy materials. In the long term, our results might contribute to developing novel materials with some functions that are impossible with ordinary materials.”

Next the team wants to explore how this phenomenon plays out with other diverse species of bacteria in different environments. Ongoing research has so far shown that there are different ways in which cells can become crowded together. Takeuchi said: “Our results indicate that dense bacteria can drastically change their mobility and mechanical properties at the population level, by a minute change in the cell density. This information could be used to regulate or control dense bacteria formations in the future. Through our work, we hope to make deeper and broader connections between statistical physics and life science.”

#####

Paper

Hisay Lama, Masahiro J. Yamamoto, Yujiro Furuta, Takuro Shimaya, and Kazumasa A. Takeuchi. Emergence of bacterial glass. PNAS Nexus. 11th July 2024. DOI: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae238

Funding

This research was supported in part by KAKENHI from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant Nos. JP16H04033, JP19H05800, JP20H00128, JP21K20350, JP24K00593), by Core-to-Core Program “Advanced core-to-core network for the physics of self-organizing active matter (JPJSCCA20230002), and by “Planting Seeds for Research” program and Suematsu Award from Tokyo Institute of Technology.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Useful Links

Graduate School of Science: https://www.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/index.html

Department of Physics: https://www.phys.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/

Research contacts

Associate Professor Kazumasa Takeuchi

Department of Physics

Graduate School of Science,

The University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo,

Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, 113-0033, Japan

Email: takeuchi@phys.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Press contact

Mrs. Nicola Burghall (she/her)

Public Relations Group, The University of Tokyo,

7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8654, Japan

press-releases.adm@gs.mail.u-tokyo.ac.jp

About the University of Tokyo

The University of Tokyo is Japan’s leading university and one of the world’s top research universities. The vast research output of some 6,000 researchers is published in the world’s top journals across the arts and sciences. Our vibrant student body of around 15,000 undergraduate and 15,000 graduate students includes over 4,000 international students. Find out more at www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/ or follow us on X (formerly Twitter) at @UTokyo_News_en.

END

Bacteria form glasslike state

Densely packed E.coli form an immobile material similar to colloidal glass

2024-07-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Prestigious MERIT grant funds research on how the immune system can banish HIV

2024-07-11

Weill Cornell Medicine has received $4.2 million to study how the immune system in some people infected with HIV can keep the virus under control, which could lead to novel therapeutic strategies for thwarting or eliminating HIV. Dr. Brad Jones, associate professor of immunology in medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Weill Cornell Medicine, was awarded a MERIT grant from the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The “Method for Extending Research in Time” (MERIT) grant provides ...

Research reveals novel CARS E795V mutation as cause of inherited Parkinson's disease

2024-07-11

According to Science Alert, neuroscientists from Johns Hopkins University have recently discovered a new treatment for Parkinson's disease using an FDA-approved cancer drug. A recent study published in Neuroscience Bulletin reveals the genetic cause of Parkinson's disease. The study discovered that a mutation in the Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase (CARS) gene (c.2384A>T; p.Glu795Val; E795V) is responsible, offering a new path for prevention and control of the disease. This research was conducted by a team led by Zhang Jianguo, including researcher ...

Narcissism decreases with age, study finds

2024-07-11

People tend to become less narcissistic as they age from childhood through older adulthood, according to a study published by the American Psychological Association. However, differences among individuals remain stable over time -- people who are more narcissistic than their peers as children tend to remain that way as adults, the study found.

“These findings have important implications given that high levels of narcissism influence people’s lives in many ways -- both the lives of the narcissistic individuals themselves and, maybe even more, the lives of their families and friends,” said lead author Ulrich Orth, PhD, of the University of Bern in Switzerland.

The ...

Scientists call for ‘major initiative’ to study whether geoengineering should be used on glaciers

2024-07-11

A group of scientists have released a landmark report on glacial geoengineering—an emerging field studying whether technology could halt the melting of glaciers and ice sheets as climate change progresses.

The white paper represents the first public efforts by glaciologists to assess possible technological interventions that could help address catastrophic sea-level rise scenarios.

While it does not endorse any specific interventions, it calls for a “major initiative” in the next decades to research which, if any, interventions could and should be ...

Mount Sinai secures over $4 million grant from National Institutes of Health to study alopecia areata and atopic dermatitis in people with Down Syndrome

2024-07-11

New York, NY (July 11, 2024) – The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai is embarking on biomedical research aiming to set new standard-of-care protocols for treating alopecia areata and atopic dermatitis in people with Down syndrome, or trisomy 21.

Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, the Waldman Professor and Chair of Dermatology at Icahn Mount Sinai, has been awarded more than $4 million for a five-year National Institutes of Health (NIH) R61/R33 grant to evaluate the long-term safety, efficacy, and mechanisms of medications known as JAK inhibitors in patients with Down syndrome. The medications have been approved ...

How risk-averse are humans when interacting with robots?

2024-07-11

How do people like to interact with robots when navigating a crowded environment? And what algorithms should roboticists use to program robots to interact with humans?

These are the questions that a team of mechanical engineers and computer scientists at the University of California San Diego sought to answer in a study presented recently at the ICRA 2024 conference in Japan.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating robots that infer human perception of risk for intelligent decision-making in everyday settings,” said Aamodh Suresh, first author of the study, who earned his Ph.D. in the research group of Professor Sonia Martinez Diaz ...

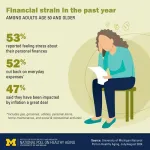

An unequal toll of financial stress: Poll of older adults shows different impacts related to health and age

2024-07-11

Inflation rates may have cooled off recently, but a new poll shows many older adults are experiencing financial stress – especially those who say they’re in fair or poor physical health or mental health.

Women and those age 50 to 64 are more likely than men or people over age 65 to report feeling a lot of stress related to their personal finances. So are people age 50 and older who say they’re in fair or poor physical or mental health.

In all, 47% of people age 50 and older said inflation had impacted them a great deal in the past year, and 52% said they ...

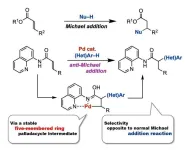

One-step synthesis of pharmaceutical building blocks: new method for anti-Michael reaction

2024-07-11

In 1887, chemist Sir Arthur Michael reported a nucleophilic addition reaction to the β-position of α,β- unsaturated carbonyl compounds. These reactions, named Michael addition reactions, have been extensively studied to date. In contrast, the anti-Michael addition reaction, referring to the nucleophilic addition reaction to the α-position, has been difficult to achieve. This is due to the higher electrophilicity of the β-position compared to the α-position. Previous attempts to overcome these difficulties have involved two main methods. The first is restricting the addition position via intramolecular reactions, ...

Urban seagulls still prefer seafood

2024-07-11

Seagull chicks raised on an “urban” diet still prefer seafood, new research shows.

University of Exeter scientists studied herring gull chicks that had been rescued after falling off roofs in towns across Cornwall, UK.

Raised in captivity (before being released), they were given either a “marine” diet consisting mainly of fish and mussels, or an “urban” diet containing mostly bread and cat food.

Every few days the gull chicks were presented with a choice of all four foods in different bowls, to test which they preferred – and all gulls strongly favoured fish.

“Our results suggest that, even when reared on an ‘urban’ ...

Understanding the origin of superconductivity in high-temperature copper oxide superconductors

2024-07-11

Superconductors are materials that can conduct electricity with zero resistance when cooled to a certain temperature, called the critical temperature. They have applications in many fields, including power grids, maglev trains, and medical imaging. High-temperature superconductors, which have critical temperatures higher than normal superconductors have significant potential for advancing these technologies. However, the mechanisms behind their superconductivity remain unclear.

Copper oxides or cuprates, a class of high-temperature superconductors, exhibit superconductivity ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Duke-NUS scientists identify more effective way to detect poultry viruses in live markets

Low-intensity treadmill exercise preconditioning mitigates post-stroke injury in mouse models

How moss helped solve a grave-robbing mystery

How much sleep do teens get? Six-seven hours.

Patients regain weight rapidly after stopping weight loss drugs – but still keep off a quarter of weight lost

GLP-1 diabetes drugs linked to reduced risk of addiction and substance-related death

Councils face industry legal threats for campaigns warning against wood burning stoves

GLP-1 medications get at the heart of addiction: study

Global trauma study highlights shared learning as interest in whole blood resurges

Almost a third of Gen Z men agree a wife should obey her husband

Trapping light on thermal photodetectors shatters speed records

New review highlights the future of tubular solid oxide fuel cells for clean energy systems

Pig farm ammonia pollution may indirectly accelerate climate warming, new study finds

Modified biochar helps compost retain nitrogen and build richer soil organic matter

First gene regulation clinical trials for epilepsy show promising results

Life-changing drug identified for children with rare epilepsy

Husker researchers collaborate to explore fear of spiders

Mayo Clinic researchers discover hidden brain map that may improve epilepsy care

NYCST announces Round 2 Awards for space technology projects

How the Dobbs decision and abortion restrictions changed where medical students apply to residency programs

Microwave frying can help lower oil content for healthier French fries

In MS, wearable sensors may help identify people at risk of worsening disability

Study: Football associated with nearly one in five brain injuries in youth sports

Machine-learning immune-system analysis study may hold clues to personalized medicine

A promising potential therapeutic strategy for Rett syndrome

How time changes impact public sentiment in the U.S.

Analysis of charred food in pot reveals that prehistoric Europeans had surprisingly complex cuisines

As a whole, LGB+ workers in the NHS do not experience pay gaps compared to their heterosexual colleagues

How cocaine rewires the brain to drive relapse

Mosquito monitoring through sound - implications for AI species recognition

[Press-News.org] Bacteria form glasslike stateDensely packed E.coli form an immobile material similar to colloidal glass