(Press-News.org) CLEVELAND—The evolution of resistance to diseases, from infectious illnesses to cancers, poses a formidable challenge.

Despite the expectation that resistance-conferring mutations would dwindle in the absence of treatment due to a reduced growth rate, preexisting resistance is pervasive across diseases that evolve—like cancer and pathogens—defying conventional wisdom.

In cancer, it is well known that small numbers of drug-resistant cells likely exist in tumors even before they’re treated. In something of a paradox, before treatment, these mutants have been repeatedly shown to have lower fitness than the surrounding ancestor cells from which they arose. It leads to a scenario that seems to break Darwin’s rules: Why do these least fit cells survive?

In a new study, researchers at Case Western Reserve University and Cleveland Clinic reveal a fascinating discovery: Interactions between these mutants and their ancestors, like two species in an ecosystem, may hold the key to understanding this paradox.

Their findings suggest these ecological interactions play a pivotal role in reducing the costs of resistance, providing a path to survival for preexisting resistance. And not just in lung cancer, but across various biomedical contexts where drug resistance is a challenge, including other cancers, pathogens and even parasites.

The study

Combining computer simulations and analytical results, the study establishes a mathematical framework to examine the impact of these ecological interactions on the evolutionary dynamics of resistance.

“This is a really exciting finding because it settles some fundamental disagreements between classical population genetics and theoretical ecology,” said the study’s principal investigator Jacob Scott, staff physician-scientist at Cleveland Clinic and an associate professor of physics and medicine at Case Western Reserve. Scott is also associate director for data science at the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center.

The study also highlights the clinical relevance of these findings by genetically engineering common resistance mechanisms observed in non-small-cell lung cancer, a disease notorious for preexisting resistance to targeted therapies, and the leading cause of cancer death in the United States.

Each genetically engineered cancer cell line experienced a benefit from being with its ancestor, in the group’s evolutionary game assay when cultured with their treatment sensitive ancestor, just as the new theory predicted—bringing closure to the paradox.

“Our findings offer an attractive new hypothesis for why treatment resistance is so common: The resistant cells are saved from extinction by the other cells surrounding them through an ecological mechanism,” said Jeff Maltas, the study’s lead author and a post-doctoral fellow at Case Western Reserve. “These results provide a novel treatment strategy: designing treatments that disrupt the ecological interaction that allows resistance to gain a foothold in the first place, rather than developing new drugs for increasingly resistant populations.”

This multidisciplinary research, including physics, genetics, theoretical ecology and mathematical oncology, published in PRX Life, represents a significant step toward understanding resistance evolution. The hope is it may lead to innovative approaches to fighting cancer and infectious diseases, the researchers said.

###

Case Western Reserve University is one of the country's leading private research institutions. Located in Cleveland, we offer a unique combination of forward-thinking educational opportunities in an inspiring cultural setting. Our leading-edge faculty engage in teaching and research in a collaborative, hands-on environment. Our nationally recognized programs include arts and sciences, dental medicine, engineering, law, management, medicine, nursing and social work. About 6,200 undergraduate and 6,100 graduate students comprise our student body. Visit case.edu to see how Case Western Reserve thinks beyond the possible.

END

Unlocking the mystery of preexisting drug resistance: New study sheds light on cancer evolution

2024-07-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New study reveals critical role of C1q protein in neuronal function and aging

2024-07-15

BOSTON, Mass. (July 15, 2024)—A groundbreaking study conducted at the lab of Beth Stevens, PhD, at Boston Children’s Hospital has revealed that an immune protein impacts neuronal protein synthesis in the aging brain. Previous work from the Stevens lab had uncovered that immune cells in the central nervous system, microglia, help prune synapses in the developing brain by tagging synapses with the immune protein C1q. New research led by Nicole Scott-Hewitt, published in Cell, shows that neurons can also internalize C1q. C1q seems to influence protein production inside neurons by interacting with ribosomal proteins, RNA-binding proteins, and ...

New research demonstrates potential for increasing effectiveness of popular diabetes, weight-loss drugs

2024-07-15

A network of proteins found in the central nervous system could be harnessed to increase the effectiveness and reduce the side effects of popular diabetes and weight-loss drugs, according to new research from the University of Michigan.

The study, appearing today in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, focused on two proteins called melanocortin 3 and melanocortin 4 found primarily on the surface of neurons in the brain that play a central role in regulating feeding behavior and maintaining the body's energy balance.

Melanocortin ...

Understanding the 3D ice-printing process to create micro-scale structures

2024-07-15

Advances in 3D printing have enabled many applications across a variety of disciplines, including medicine, manufacturing, and energy. A range of different materials can be used to print both simple foundations and fine details, allowing for the creation of structures with tailored geometries.

However, creating structures with micro-scale, precise internal voids and channels still poses challenges. Scaffolds used in tissue engineering, for example, must contain a three-dimensional complex network of conduits that mimic the human vasculature. With traditional additive manufacturing, where the material is deposited layer ...

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia researchers develop antioxidant strategy to address mitochondrial dysfunction caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus

2024-07-15

Philadelphia, July 15, 2024 – Building upon groundbreaking research demonstrating how the SARS-CoV-2 virus disrupts mitochondrial function in multiple organs, researchers from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) demonstrated that mitochondrially-targeted antioxidants could reduce the effects of the virus while avoiding viral gene mutation resistance, a strategy that may be useful for treating other viruses. The preclinical findings were recently published in the journal Proceedings ...

How climate change is altering the Earth’s rotation

2024-07-15

Climate change is causing the ice masses in Greenland and Antarctica to melt. Water from the polar regions is flowing into the world’s oceans –and especially into the equatorial region. “This means that a shift in mass is taking place, and this is affecting the Earth’s rotation,” explains Benedikt Soja, Professor of Space Geodesy at the Department of Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering at ETH Zurich.

“It’s like when a figure skater does a pirouette, first holding her arms close to her body and then stretching ...

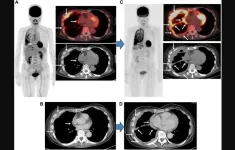

Comparison of FDG-PET/CT and CT for treatment evaluation of patients with unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma

2024-07-15

“FDG-PET is generally considered as a useful metabolic evaluation tool, while it is also thought to have an emerging role for assessment of systemic therapy response.”

BUFFALO, NY- July 15, 2024 – A new research paper was published in Oncotarget's Volume 15 on June 20, 2024, entitled, “Comparison of FDG-PET/CT and CT for evaluation of tumor response to nivolumab plus ipilimumab combination therapy and prognosis prediction in patients with unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma.”

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is an aggressive neoplasm and affected ...

New concept explains how tiny particles navigate water layers – with implications for marine conservation

2024-07-15

A new UBC study published recently in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS) has unveiled insights into how microscopic organisms such as marine plankton move through water with different density layers.

Researchers Gwynn Elfring and Vaseem Shaik found that density layers, created by variations in temperature or salinity, influence the swimming direction and speed of tiny particles navigating a liquid.

Pushers and pullers

“There are two different types of microscopic swimmers – ...

New research shows a frictionless state can be achieved at macroscale

2024-07-15

UTICA, NY – The president of SUNY Polytechnic Institute (SUNY Poly), Dr. Winston “Wole” Soboyejo, and postdoctoral researcher, Dr. Tabiri Kwayie Asumadu, have published a revolutionary new paper titled, "Robust Macroscale Superlubricity on Carbon-Coated Metallic Surfaces." This paper explores an innovative approach to reducing friction on metallic surfaces – a significant advancement that could have major real-world impacts.

The study shows that superlubricity – a state with virtually no friction that was once believed to only be achievable at nanoscale – can now be maintained at macroscale for extended time ...

A novel and unique neural signature for depression revealed

2024-07-15

HOUSTON - (July 15, 2024) - As parents, teachers and pet owners can attest, rewards play a huge role in shaping behaviors in humans and animals. Rewards – whether as edible treats, gifts, words of appreciation or praise, fame or monetary benefits – act as positive reinforcement for the associated behavior. While this correlation between reward and future choice has been used as a well-established paradigm in neuroscience research for well over a century, not much is known about the neural process underlying it, namely how the brain encodes, ...

Academic psychiatry urged to collaborate with behavioral telehealth companies

2024-07-15

Waltham — July 15, 2024 — The strengths of academic psychiatry departments and the fast-growing private telehealth sector are complementary, according to a Perspective article published in Harvard Review of Psychiatry, part of the Lippincott portfolio from Wolters Kluwer. Justin A. Chen, MD, MPH, a psychiatrist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, and colleagues reviewed literature on provision of outpatient mental health care in the United States. They concluded that academic psychiatry departments and telehealth companies could mutually benefit from strategic collaboration.

Academic medical centers struggle to ...