(Press-News.org)

There’s still much to learn about how doxorubicin, a 50-year-old chemotherapy drug, causes its most concerning side effects. While responsible for saving many lives, this treatment sometimes causes cardiac damage that stiffens the heart and puts a subset of patients at risk for future heart failure. To better understand and potentially control such complications, Tufts University School of Medicine and Tufts Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences researchers have isolated the immune cells that become overactive when patients take doxorubicin. The team’s findings appear July 17 in the journal Nature Cardiovascular Research.

Doxorubicin is a top choice for oncologists as a first line of defense against various cancers because of its ability to slow or stop cell division and thus tumor growth. It has been shown that the drug can induce a pro-inflammatory response in the heart, but there is no intervention that is broadly effective at preventing this, and it’s not clear how it happens or why, so Tufts scientists are trying to close these gaps.

Their investigation found elevated levels of potent virus-killing CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells—a type of immune cell—and their molecular attractors in the blood of healthy mice after beginning doxorubicin. This observation was further confirmed in dozens of canine and human lymphoma patients. Further mouse model work showed that these T-cells not only moved to the heart and directly interacted with heart tissue but that removing them relieved cardiac inflammation and fibrosis—the scarring of the heart muscles due to injury.

“Our study is the first to show that a specific cell type can cause chronic inflammation in the heart after doxorubicin treatment and the first time T-cells have been implicated in this disease,” says first author Abe Bayer, a student in the Tufts MD/PhD immunology program. “This suggests that blocking T-cells from going into the heart might be a strategy to make a medication to prevent the cardiac damage associated with the drug.”

Bayer and his colleagues figured out that something about doxorubicin is causing CD8+ T-cells to become dysfunctional by making them recognize something in the heart as foreign, leading them to become overactive. The reason the chemotherapy drug draws the T-cells from the blood to attack cardiac tissue has yet to be defined, but that will be the focus of future work.

The research team found that, once in the heart, the CD8+ T-cells can cause changes to the organ, leaving the cardiac tissue scarred, highly fibrotic, and less able to perform. Their research showed that in mice the T-cells are releasing molecules that are meant to cause cell death, which are normally intended to combat viruses and other invaders, but these molecules cause fibrosis and stiffen the heart, preventing it from contracting well.

“This work aims to prevent people from dying, whether from heart disease or cancer, and that means ensuring that people can take these powerful chemotherapy drugs safely,” says senior author Pilar Alcaide, Kenneth and JoAnn G. Wellner Professor at the School of Medicine. “While we don’t know what the solutions will look like, this study opens many doors to potential prevention strategies that protect the heart while permitting this drug to be effective for cancer cells.”

In addition to investigating how to block CD8+ T-cells from entering the heart without affecting doxorubicin’s ability to fight cancer, future research from the team will also explore whether the molecules that attract T-cells to the heart, called chemokines, could serve as biomarkers to monitor or predict cardiac damage, allowing for more personalized and safer treatment plans for patients.

The Tufts team was able to conduct such an in-depth, cross-species study due to the availability of canine and human cancer patient samples on campus as well as in the wider network of Boston hospitals, particularly the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Dogs experience the same side-effects to doxorubicin as people, and the researchers are working closely with co-author Cheryl London, associate dean for research and graduate education and the Anne Engen and Dusty Professor of Comparative Oncology at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University, to apply what they learn to the treatment of our animal companions.

“I’m really excited about this paper because it’s something brand new in a very old field,” says Bayer. “It’s hard to do, but I hope it inspires more people to not look at a pile of literature and be afraid to add something on top. Science is too complicated to say we’ve figured it all out.”

Research reported in this article was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and a Tufts Springboard grant. Complete information on authors, funders, methodology, and conflicts of interest is available in the published paper.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

END

The Gerontological Society of America (GSA) — the nation’s largest interdisciplinary organization devoted to the field of aging — has chosen Jiska Cohen-Mansfield, PhD, FGSA, of Tel Aviv University as the 2024 recipient of the Robert W. Kleemeier Award.

This distinguished honor is given annually to a GSA member in recognition for outstanding research in the field of gerontology. It was established in 1965 in memory of Robert W. Kleemeier, PhD, a former president of the Society whose contributions to the quality of life through research in aging were exemplary.

The award presentation will take place at GSA’s ...

The Gerontological Society of America (GSA) — the nation’s largest interdisciplinary organization devoted to the field of aging — has chosen Lisa L. Barnes, PhD, FGSA, of Rush University Medical Center as the 2024 recipient of the James Jackson Outstanding Mentorship Award.

This distinguished honor is given annually and recognizes individuals who have exemplified outstanding commitment and dedication to mentoring minority researchers in the field of aging. It was renamed in 2021 in memory of James Jackson, PhD, FGSA, a pioneering psychologist ...

The Science

Polyphenols are a diverse group of organic compounds produced by plants. These compounds are often toxic to microorganisms. In peatlands, scientists thought that microorganisms avoided this toxicity by degrading polyphenols using an enzyme that requires oxygen. However, when there is little or no oxygen, like after flooding due to climate induced thawing, the enzyme is inactive, and polyphenols accumulate. This inhibits microbes’ carbon cycling. In this study, scientists mined data for thousands of microbial genomes recovered from Stordalen Mire, an Arctic peatland in Sweden. They discovered that these microorganisms used alternative polyphenol-active ...

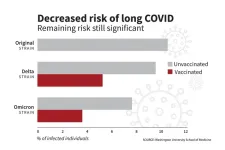

The risk of developing long COVID has decreased significantly over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to an analysis of data led by Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Researchers attributed about 70% of the risk reduction to vaccination against COVID-19 and 30% to changes over time, including the SARS-CoV-2 virus’s evolving characteristics and improved detection and management of COVID-19.

The research is published July 17 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“The research on declining rates ...

The University of Freiburg is establishing a new tenure track professorship in Earth and Planetary Geodynamics at the Faculty of Environment and Natural Resources, made possible by a 1.71 million euro grant from the Volkswagen Foundation. The new tenure track professorship is part of a comprehensive strategic initiative for combining Earth system sciences with planetary sciences at the University that also includes the establishment of a new Earth System Simulation Lab (EaSySim) and the introduction of an Earth Sciences ...

A research team at the Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences (VMBS) has received a $5 million grant from the United States Department of Defense’s Defense Threat Reduction Agency to support the detection and prevention of brucellosis in Armenia.

Brucellosis, which is caused by several bacterial species of Brucella, is a zoonotic disease that can spread to humans from dogs and major livestock species, including cattle, pigs, sheep, and goats. It can have a major impact on a country’s public health and agricultural economy.

The team of Texas A&M researchers, led by VMBS Associate Professor Dr. Angela Arenas, will ...

MINNEAPOLIS – For people with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS), a new study has found that the drug ofatumumab is more effective than teriflunomide at helping people across racial and ethnic groups reach a period of no disease activity. The study is published in the July 17, 2024, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology. Ofatumumab, a monoclonal antibody, is a newer drug for treating MS. Teriflunomide, an immunomodulatory agent, has been available for over a decade.

MS is a disease in ...

MINNEAPOLIS – Insurance coverage, ethnicity and location may all play a role in a person’s ability to receive care after a stroke, according to a study published in the July 17, 2024, online issue of Neurology® Clinical Practice, an official journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

“Receiving the right care after a stroke is crucial to recovery and minimizing disability,” said study author Shumei Man, MD, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio and a member of the American Academy of Neurology. “Unfortunately, decisions about care may be influenced by factors such as race, insurance, and geographic location. Our study ...

A majority of people in Afghanistan support human rights for Afghan women, and men are especially likely to support women’s rights when primed to think about their eldest daughters, according to a study published July 17, 2024, in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, by Kristina Becvar and colleagues from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Human rights groups have been concerned for the rights of Afghan women in particular since the Taliban took control of Kabul in 2021. Since then, Afghan ...

Scientists at the University of Sydney and Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine have made a remarkable discovery: a commonly used blood thinner, heparin, can be repurposed as an inexpensive antidote for cobra venom.

Cobras kill thousands of people a year worldwide and perhaps a hundred thousand more are seriously maimed by necrosis – the death of body tissue and cells – caused by the venom, which can lead to amputation.

Current antivenom treatment is expensive and does not effectively ...