(Press-News.org) In a new review paper, researchers from the Universities of Arizona, Oxford and Leeds analyzed dozens of previous studies into long COVID to examine the number and range of people affected, the underlying mechanisms of disease, the many symptoms that patients develop, and current and future treatments.

Long COVID, also known as Post-COVID-19 condition, is generally defined as symptoms persisting for three months or more after acute COVID-19. The condition can affect and damage many organ systems, leading to severe and long-term impaired function and a broad range of symptoms, including fatigue, cognitive impairment – often referred to as ‘brain fog’ – breathlessness and pain.

Long COVID can affect almost anyone, including all age groups and children. It is more prevalent in females and those of lower socioeconomic status, and the reasons for such differences are under study. The researchers found that while some people gradually get better from long COVID, in others the condition can persist for years. Many people who developed long COVID before the advent of vaccines are still unwell.

“Long COVID is a devastating disease with a profound human toll and socioeconomic impact,” said Janko Nikolich, MD, PhD, senior author of the paper, director of the Aegis Consortium at the U of A Health Sciences, professor and head of the Department of Immunobiology at the U of A College of Medicine – Tucson, and BIO5 Institute member. “By studying it in detail, we hope to both understand the mechanisms and to find targets for therapy against this, but potentially also other infection-associated complex chronic conditions such as myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia.”

If a person has been fully vaccinated and is up to date with their boosters, their risk of long COVID is much lower. However, 3%-5% of people worldwide still develop long COVID after an acute COVID-19 infection. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, long COVID affects an estimated 4%-10% of the U.S. adult population and 1 in 10 adults who had COVID develop long COVID.

The review study also found that a wide range of biological mechanisms are involved, including persistence of the original virus in the body, disruption of the normal immune response, and microscopic blood clotting, even in some people who had only mild initial infections.

There are no proven treatments for long COVID yet, and current management of the condition focuses on ways to relieve symptoms or provide rehabilitation. Researchers say there is a dire need to develop and test biomarkers such as blood tests to diagnose and monitor long COVID and to find therapies that address root causes of the disease.

People can lower their risk of developing long COVID by avoiding infection – wearing a close-fitting mask in crowded indoor spaces, for example – taking antivirals promptly if they do catch COVID-19, avoiding strenuous exercise during such infections, and ensuring they are up to date with COVID vaccines and boosters.

“Long COVID is a dismal condition but there are grounds for cautious optimism,” said Trisha Greenhalgh, lead author of the study and professor at Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. “Various mechanism-based treatments are being tested in research trials. If proven effective, these would allow us to target particular subgroups of people with precision therapies. Treatments aside, it is becoming increasingly clear that long COVID places an enormous social and economic burden on individuals, families and society. In particular, we need to find better ways to treat and support the ‘long-haulers’ – people who have been unwell for two years or more and whose lives have often been turned upside down.”

The full paper, “Long COVID: a clinical update,” is published in The Lancet.

END

New study highlights scale and impact of long COVID

2024-08-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How the rising earth in Antarctica will impact future sea level rise

2024-08-02

COLUMBUS, Ohio – The rising earth beneath the Antarctic Ice Sheet will likely become a major factor in future sea level rise, a new study suggests.

Despite feeling like a stationary mass, most solid ground is undergoing a process of deformation, sinking and rising in response to many environmental factors. In Antarctica, melting glacial ice means less weight on the bedrock below, allowing it to rise. How the rising earth interacts with the overlying ice sheet to affect sea level rise is not well-studied, said Terry Wilson, co-author of the study and a senior research scientist at the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center ...

Research spotlight: Uncovering the links between sleep struggles, substance abuse and suicidal thoughts in teens with depression

2024-08-02

Rebecca Robbins, PhD, of the Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, is the senior author of a paper published in Psychiatry Research, “Exploring sleep difficulties, alcohol, illicit drugs, and suicidal ideation among adolescents with a history of depression.”

How would you summarize your study for a lay audience?

Suicide is one of the leading causes of death for adolescents in the U.S. We know, due to previous research, that difficulty falling asleep or waking up too early as well as abuse of prescription ...

Boosting children’s voices could help to relieve significant backlogs in the family court, study says

2024-08-02

Giving children a right to be heard and taken seriously when parents separate could help couples reach sustainable child arrangements and relieve significant backlogs in the family court, avoiding unnecessary financial and emotional costs, a new study says.

Mediation, court and legal processes should provide a forum for young people’s views on post-separation arrangements being considered for them to be aired independently and factored in wherever appropriate. Giving them more agency about decisions which affect their lives and futures will help families make more effective ...

Study yields new insights into the link between global warming and rising sea levels

2024-08-02

A McGill-led study suggests that Earth's natural forces could substantially reduce Antarctica’s impact on rising sea levels, but only if carbon emissions are swiftly reduced in the coming decades. By the same token, if emissions continue on the current trajectory, Antarctic ice loss could lead to more future sea level rise than previously thought.

The finding is significant because the Antarctic Ice Sheet is the largest ice mass on Earth, and the biggest uncertainty in predicting future sea levels is how this ice will respond to climate change.

“With nearly 700 million people living in coastal areas and the potential ...

Controlling thickness in fruit fly hearts reveals new pathway for heart disease

2024-08-02

Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys and Salk Institute for Biological Studies have uncovered a new role for a protein known for its role in the brain helping control feelings of hunger or satiety, as well as in the liver to aid the body in maintaining a balance of energy during fasting. The new study shows that this protein also supports the maintenance of heart structure and function, but when it is overactive it causes thickening of the heart muscle, which is associated with heart disease.

Excessive thickening of the heart muscle—known as cardiac hypertrophy—is often ...

Improving cat food flavors with the help of feline taste-testers

2024-08-02

Cats are notoriously picky eaters. But what if we could design their foods around flavors that they’re scientifically proven to enjoy? Researchers publishing in ACS’ Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry used a panel of feline taste-testers to identify favored flavor compounds in a series of chicken-liver-based sprays. The cats particularly enjoyed the sprays that contained more free amino acids, which gave their kibble more savory and fatty flavors.

Cats have a more acute sense of smell than humans, and the aroma of their food plays a big role in whether they’ll eat or snub what their owner serves for dinner. Feline palates are also more sensitive to umami ...

Subclinical hypothyroidism in early pregnancy associated with more than quadrupled risk of reduced thyroid function within 5 years of delivery

2024-08-02

A new study has shown that subclinical hypothyroidism diagnosed before 21 weeks of pregnancy is associated with more than fourfold higher rates of overt hypothyroidism or thyroid replacement therapy within 5 years of delivery. The study is published in the peer-reviewed journal Thyroid®, the official journal of the American Thyroid Association® (ATA®).

Subclinical hypothyroidism, or a change in the levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) that isn’t severe enough to cause symptoms, ...

BNP-Track algorithm offers a clearer picture of biomolecules in motion

2024-08-02

It’s about to get easier to catch and analyze a high-quality image of fast-moving molecules. Assistant Professor Ioannis Sgouralis, Department of Mathematics, and colleagues have developed an algorithm that adds a new level to microscopy: super-resolution in motion.

The cutting-edge advancement of super-resolution microscopy was recognized with the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for its groundbreaking innovation. It improves optical microscopy with a suite of techniques that overcome the inherent limitations set by the physics of light. The high-frequency oscillations of light waves escape detection ...

Not the day after tomorrow: Why we can't predict the timing of climate tipping points

2024-08-02

A new study published in Science Advances reveals that uncertainties are currently too large to accurately predict exact tipping times for critical Earth system components like the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), polar ice sheets, or tropical rainforests. These tipping events, which might unfold in response to human-caused global warming, are characterized by rapid, irreversible climate changes with potentially catastrophic consequences. However, as the new study shows, predicting when these events will occur is more difficult than previously thought.

Climate scientists from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and ...

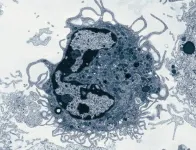

Discovery of a new population of macrophages promoting lung repair after viral infections

2024-08-02

Researchers at the University of Liège (Belgium) have discovered a new population of macrophages, important innate immune cells that populate the lungs after injury caused by respiratory viruses. These macrophages are instrumental in repairing the pulmonary alveoli. This groundbreaking discovery promises to revolutionize our understanding of the post-infectious immune response and opens the door to new regenerative therapies.

Respiratory viruses, typically causing mild illness, can have more serious consequences, as shown during the Covid-19 pandemic, including severe cases requiring hospitalization and the chronic sequelae of "long Covid." These conditions ...