(Press-News.org) Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys and Salk Institute for Biological Studies have uncovered a new role for a protein known for its role in the brain helping control feelings of hunger or satiety, as well as in the liver to aid the body in maintaining a balance of energy during fasting. The new study shows that this protein also supports the maintenance of heart structure and function, but when it is overactive it causes thickening of the heart muscle, which is associated with heart disease.

Excessive thickening of the heart muscle—known as cardiac hypertrophy—is often the result of the heart trying to maintain proper blood flow while adapting to changes caused by other heart diseases such as hypertension or heart valve malfunction. Hypertrophy in the heart’s left ventricle affects as many as half of all patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, and the thickening of this chamber is known to lead to more adverse cardiovascular events such as heart attacks, strokes and sudden cardiac deaths.

“We’re interested in this because heart disease is the leading cause of death in the industrialized world,” says Karen Ocorr, PhD, an assistant professor in the Development, Aging and Regeneration Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys. “And for most of the situations—including cardiac hypertrophy—we still don't really know the root causes.”

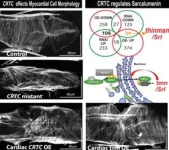

Ocorr, her lab and her collaborators at the Salk Institute published results on August 1, 2024, in Cell Reports, showing that a protein called CREB-regulated transcription co-activator (CRTC) is likely one of the underlying sources of cardiac hypertrophy.

“People have done a lot to understand how CRTC works in neurons and the liver, but no one has really shown that it functions in the heart,” says Cristiana Dondi, PhD, a postdoctoral associate in the Ocorr lab and first author on the study. “We were determined to change that.”

The research team knew that CRTC interacted with an enzyme called calcineurin that had been connected to cardiac hypertrophy in prior studies. They began by creating fruit flies genetically engineered with an inactive form of the gene that carries the blueprint for CRTC.

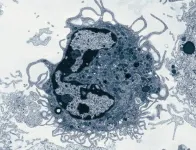

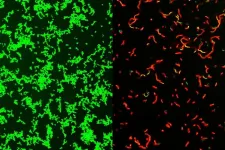

Upon testing heart rhythm with tiny electrodes and heart function with high-speed video imaging, the fruit flies without active CRTC had more difficulty recovering normal heart rhythms after experiencing stress than did normal fruit flies. The engineered flies also had thinner heart muscles with diminished function and were unable to circulate blood as effectively.

“In addition to the structural defects we found in the flies with the CRTC gene systemically knocked out, we also saw an incredible amount of fibrosis,” notes Ocorr, senior author on the study. “We hardly ever see that in normal hearts, so that really struck me because fibrosis is a hallmark of heart disease.”

To make sure that these observations were specifically connected to a lack of CRTC in the heart rather than a broader developmental defect in other cells that precipitated the phenomena, the team investigated flies that only failed to make the CRTC protein in the heart while other tissues maintained their CRTC production.

“We saw very similar results to the studies with our whole-body knockout flies, so that helped us confirm that the changes were specific to a lack of CRTC in the heart,” says Dondi. To be even more sure, the group repeated the experiments eliminating CRTC only in cells surrounding the heart called pericardial cells, then in the nervous system and, finally in the fly’s fat body considered to be the fly’s equivalent of a liver. But none of these manipulations had the same effects on the heart, adding more weight to a crucial cardiac role for CRTC.

In addition to examining the effects of an absence of CRTC in the heart, the team also investigated what would happen if the heart produced too much CRTC, which is known as overexpression.

“It seems to be two sides of a structural coin,” adds Ocorr. “Without CRTC, the muscle fibers within the heart cells get disorganized. They start to have big gaps between them and then the ability of the heart to contract is reduced.”

“If you overexpress CRTC, you get the opposite. You get a lot more of the proteins than is normally needed for the heart and that's what makes it bigger and causes hypertrophy. Although the heart is larger, it becomes too musclebound and does not function as well as a normal heart.”

In addition to finding a new agent responsible for cardiac hypertrophy alongside the well-established calcineurin enzyme, Dondi, Ocorr, and their collaborators discovered a protein whose production is controlled by CRTC and likely contributes to the heart defects observed in this publication.

“We checked how genes worked differently in the hearts with too little or too much CRTC activity,” says Dondi. “After filtering for those present in heart cells, we narrowed the list to 15 genes.”

One of these 15 genes is the fruit fly’s equivalent of the human gene Sarcalumenin which was found to be more active when CRTC was overexpressed and less active when CRTC was silenced. When the researchers prevented the production of this protein, they observed similar effects on heart structure and function as in the earlier experiments centered on CRTC. Because the loss of this protein caused hearts to be thinner the team proposed naming this gene “thinman.”

“This was another piece of evidence that CRTC controls the production of ‘thinman’ in flies, and probably also Sarcalumenin in humans, during normal heart maintenance,” says Ocorr. “The thinman gene contains instructions for proteins involved in managing calcium levels in skeletal and heart muscle cells. If something happens to CRTC, then you lose Sarcalumenin or thinman and you get calcium overload and muscle disorganization. Our studies show the CRTC-thinman connection is a novel pathway in cardiac hypertrophy, which is a very exciting new discovery in the field of heart research.”

“This finding opens a lot of possibilities for learning more about these signaling molecules and using them as targets for drugs to treat heart conditions. Sarcalumenin also has been linked to muscular dystrophy, so we see many opportunities for expanding on this work to find potential treatments for other conditions in addition to heart disease.”

Additional authors on the study include Georg Vogler, Anjali Gupta, Stanley Walls, Anaïs Kervedec, James Marchant, Michaela R. Romero, Soda Diop, Jason Goode, John B. Thomas, Alex Colas, Rolf Bodmer and Marc Montminy.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, the Clayton Foundation for Medical Research and the Kieckhefer Foundation.

The study’s DOI is 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114549.

END

Controlling thickness in fruit fly hearts reveals new pathway for heart disease

A new study in Cell Reports details how a protein previously associated with regulating metabolism in the liver also plays a part in maintaining a healthy heart by ensuring that the heart wall is neither too thick nor too thin

2024-08-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Improving cat food flavors with the help of feline taste-testers

2024-08-02

Cats are notoriously picky eaters. But what if we could design their foods around flavors that they’re scientifically proven to enjoy? Researchers publishing in ACS’ Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry used a panel of feline taste-testers to identify favored flavor compounds in a series of chicken-liver-based sprays. The cats particularly enjoyed the sprays that contained more free amino acids, which gave their kibble more savory and fatty flavors.

Cats have a more acute sense of smell than humans, and the aroma of their food plays a big role in whether they’ll eat or snub what their owner serves for dinner. Feline palates are also more sensitive to umami ...

Subclinical hypothyroidism in early pregnancy associated with more than quadrupled risk of reduced thyroid function within 5 years of delivery

2024-08-02

A new study has shown that subclinical hypothyroidism diagnosed before 21 weeks of pregnancy is associated with more than fourfold higher rates of overt hypothyroidism or thyroid replacement therapy within 5 years of delivery. The study is published in the peer-reviewed journal Thyroid®, the official journal of the American Thyroid Association® (ATA®).

Subclinical hypothyroidism, or a change in the levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) that isn’t severe enough to cause symptoms, ...

BNP-Track algorithm offers a clearer picture of biomolecules in motion

2024-08-02

It’s about to get easier to catch and analyze a high-quality image of fast-moving molecules. Assistant Professor Ioannis Sgouralis, Department of Mathematics, and colleagues have developed an algorithm that adds a new level to microscopy: super-resolution in motion.

The cutting-edge advancement of super-resolution microscopy was recognized with the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for its groundbreaking innovation. It improves optical microscopy with a suite of techniques that overcome the inherent limitations set by the physics of light. The high-frequency oscillations of light waves escape detection ...

Not the day after tomorrow: Why we can't predict the timing of climate tipping points

2024-08-02

A new study published in Science Advances reveals that uncertainties are currently too large to accurately predict exact tipping times for critical Earth system components like the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), polar ice sheets, or tropical rainforests. These tipping events, which might unfold in response to human-caused global warming, are characterized by rapid, irreversible climate changes with potentially catastrophic consequences. However, as the new study shows, predicting when these events will occur is more difficult than previously thought.

Climate scientists from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and ...

Discovery of a new population of macrophages promoting lung repair after viral infections

2024-08-02

Researchers at the University of Liège (Belgium) have discovered a new population of macrophages, important innate immune cells that populate the lungs after injury caused by respiratory viruses. These macrophages are instrumental in repairing the pulmonary alveoli. This groundbreaking discovery promises to revolutionize our understanding of the post-infectious immune response and opens the door to new regenerative therapies.

Respiratory viruses, typically causing mild illness, can have more serious consequences, as shown during the Covid-19 pandemic, including severe cases requiring hospitalization and the chronic sequelae of "long Covid." These conditions ...

Scientists pin down the origins of the moon’s tenuous atmosphere

2024-08-02

While the moon lacks any breathable air, it does host a barely-there atmosphere. Since the 1980s, astronomers have observed a very thin layer of atoms bouncing over the moon’s surface. This delicate atmosphere — technically known as an “exosphere” — is likely a product of some kind of space weathering. But exactly what those processes might be has been difficult to pin down with any certainty.

Now, scientists at MIT and the University of Chicago say they have identified the main process that formed the moon’s atmosphere and continues to sustain ...

More than 1 in 5 Californians who are impacted by climate events report negative effects on their mental health

2024-08-02

More than 1 in 5 Californians who are impacted by climate events report negative effects on their mental health, with young, white women and those who’ve experienced property damage being especially affected.

####

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/climate/article?id=10.1371/journal.pclm.0000387

Article Title: Exposure to climate events and mental health: Risk and protective factors from the California Health Interview Survey

Author Countries: United States

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work. END ...

New compound effective against flesh-eating bacteria

2024-08-02

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have developed a novel compound that effectively clears bacterial infections in mice, including those that can result in rare but potentially fatal “flesh-eating” illnesses. The compound could be the first of an entirely new class of antibiotics, and a gift to clinicians seeking more effective treatments against bacteria that can’t be tamed easily with current antibiotics.

The research is published Aug. 2 in Science Advances.

The compound targets gram-positive bacteria, which can cause drug-resistant staph infections, toxic shock syndrome and ...

We should think twice before calling 911 for people experiencing a mental health crisis, advocated Harvard-trained psychiatrist Dr. Rupinder Legha

2024-08-02

We should think twice before calling 911 for people experiencing a mental health crisis, advocated Harvard-trained psychiatrist Dr. Rupinder Legha, who describes the potential risks of relying on emergency services in the US for mental health crisis management.

###

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/mentalhealth/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmen.0000084

Article Title: Reconsidering calling 911: Is it time to set a new standard for mental health crisis response?

Author Countries: United States

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work. END ...

Coinfecting viruses impede each other’s ability to enter cells

2024-08-02

The process by which phages—viruses that infect and replicate within bacteria—enter cells has been studied for over 50 years. In a new study, researchers from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and Texas A&M University have used cutting-edge techniques to look at this process at the level of a single cell.

“The field of phage biology has seen an explosion over the last decade because more researchers are realizing the significance of phages in ecology, evolution, and biotechnology,” said Ido Golding (CAIM/IGOH), a professor of physics. “This work is unique ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

Anxiety, depression, and care barriers in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities

[Press-News.org] Controlling thickness in fruit fly hearts reveals new pathway for heart diseaseA new study in Cell Reports details how a protein previously associated with regulating metabolism in the liver also plays a part in maintaining a healthy heart by ensuring that the heart wall is neither too thick nor too thin