(Press-News.org) The method used across the United States to wait-list children for heart transplants does not consistently rank the sickest patients first, according to a new study led by Stanford Medicine experts.

The study will publish online Aug. 5 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Adding nuance to the wait-list system by accounting for more health factors could reduce children’s risk of dying while they await donor hearts, according to the study’s authors. A revision to the way donor hearts are assigned is already in process. The study adds evidence for why it is needed, they said.

“Wait-list mortality, which is the chance that a child will die while awaiting transplant, is higher in pediatric heart transplant than for virtually any other organ or age group,” said the study’s senior author, Christopher Almond, MD, professor of pediatrics. Almond cares for children before and after heart transplantation at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health.

“The current system is not doing a good job of capturing medical urgency, which is one of its explicit goals,” said the study’s co-lead author, economist Kurt Sweat, PhD, who conducted the research as a graduate student in economics at Stanford University. Sweat shares lead authorship of the study with Alyssa Power, MD, who was a postdoctoral scholar in pediatric heart failure/transplant at Stanford Medicine when she worked on the study.

In the last 25 years, the method used to rank infants and children on the waitlist for heart transplants has been revised three times; the most recent changes took effect in 2016. Over these decades, outcomes improved. Patients’ risk of dying on the waitlist fell from 21% to 13%, even while the total number of pediatric heart transplants increased.

But the decline in deaths is due to improvements in medical care rather than the changes in how organs are allocated, the study found.

“The goals of the current allocation system are to improve wait-list mortality and to allocate organs ethically and fairly,” Almond said. “Wait-list mortality has declined, which is a very good thing, but based on our analysis, it doesn’t look like the allocation changes made the difference. Although the intent behind the current system is to prioritize the children based on medical urgency, we saw that the system is not actually sequencing patients according to their risk.”

Three wait-list categories

Infants and children who need heart transplants are added to a waiting list maintained by the United Network for Organ Sharing, the national nonprofit that manages all organ transplants across the country.

Pediatric donor hearts are in short supply, especially for infants and smaller children, as few children die in circumstances that allow their organs to be donated. Matching must account for several factors, including geographic locations of the donor and recipient, immune compatibility, and body size. The matching system is intended to prioritize sicker children for transplant and to function equitably.

The current waitlist relies on few factors to determine where a child ranks and uses only three categories of urgency: 1A, the most urgent status, followed by 1B and 2. Factors used to determine a child’s category include what type of heart problem they have (such as congenital heart disease, which is present at birth, or cardiomyopathy, a heart muscle problem that typically develops after birth) and the medications they are receiving.

The team analyzed data from all 12,408 infants and children less than 18 years of age who were listed for heart transplant between January 20, 1999, and June 26, 2023, in the United States. To see if the current wait-list system was functioning as intended, the researchers used statistical methods, borrowed from economics, that are typically used to study markets.

“From the perspective of economics, we think about this fundamentally as an allocation problem,” Sweat said. “We’ve got this scarce resource of donor hearts, and we want to make sure they’re going to candidates who can get the most usage from them. In the case of pediatric heart transplantation, with such high wait-list mortality, what that usually looks like is you want to prioritize patients who are sicker.”

The team compared how transplant candidates were actually ranked on the waitlist with how the candidates would have ranked if the listing order was based on medical urgency.

They also considered whether improvements in wait-list outcomes aligned chronologically with the allocation changes implemented in 2006 and 2016, which were intended to create a more equitable waitlist.

Wait-list categories don’t work as intended

One of the reasons the chance of dying on the waitlist dropped during the years studied is that children on the waitlist were also healthier in recent years: At the time of transplant, they were less likely to be supported with a ventilator, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (which works like a heart-lung machine) or kidney dialysis, the study found.

However, the medical status of children within each of the three categories on the waitlist varied widely. In fact, the three categories showed significant overlap in the risk of mortality, the study found. In other words, some very sick children were categorized as priority 2 while others who were not as sick had a 1A status, meaning a less-sick child was sometimes offered a donor heart instead of a sicker child.

Also, the three wait-list categories are so broad that less-sick children were sometimes offered a heart before sicker children within the same category because they had been waiting longer, the study said.

Experts agree that a longer wait should not determine transplant priority, “because it can incentivize programs to list people early so you can build some wait time,” Almond said.

Surprisingly, wait-list rule changes in 2006 and 2016 were not linked to rapid improvements in mortality, as you would expect if the rule changes drove the improvements, the team found.

Rather, mortality decreased gradually from 1999 onward, driven by improvements to medical care, including advancements such as ventricular assist devices — mechanical pumps that support a child’s heart during the wait for transplant — and a better recognition of when to list a child for transplant. Over time, the gap in outcomes between patients of different races decreased, they found — a change that was linked to better outcomes overall.

During the study period, physicians also realized that, in infants whose immune systems are still immature, it is safe to transplant organs even when blood types don’t match. Gradual adoption of this practice helped reduce wait-list mortality in the youngest heart recipients, especially among babies with type O blood, who were previously the hardest to match, the study found.

The study’s findings suggest that the wait-list system should be revised to account for a broader range of medical factors than are currently considered — such as kidney function, liver function and whether a patient is malnourished — and should use the combination of factors to assign each child a numeric risk score to replace the current three categories, the authors said.

“The important thing is moving toward a continuous allocation score and refining it so you can account for the technological innovation that’s happening in patient care in the meantime,” Sweat said.

The revision should also account for whether a patient is healthy enough to benefit and recover from a transplant, Almond said. It would give the highest priority to children with the greatest need who have the best chance to recover from major surgery.

“It’s very challenging because if a patient is on full life support and their organs are shutting down, that person is very sick and may not survive the wait-list period. And if you transplanted them, those same risk factors mean they may not have a good outcome with transplant,” Almond said.

In September 2023, UNOS implemented a new lung transplant allocation system based on a continuous score, and the organization is drafting similar systems for other organs. It plans to have a proposal for how hearts should be allocated ready for review in 2025.

“It is really complicated to figure out how to do this well, but it appears there is still room for improvement,” Almond said.

Researchers from Stanford Medicine’s Departments of Pediatrics and Cardiothoracic Surgery, the Stanford University Department of Economics, and the University of Texas Southwestern School of Medicine contributed to the research.

The research did not receive funding.

# # #

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.

END

Heart transplant list doesn’t rank kids by medical need, Stanford Medicine-led study finds

Transplant list not ranked by medical need

2024-08-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Advancing towards a novel, highly accurate method for cervical cancer screening

2024-08-05

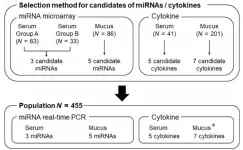

Cervical cancer is a highly prevalent cancer, with approximately 500,000 new cases diagnosed each year. Shockingly, the number of individuals diagnosed with precursor lesions in the cervix—also known as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)—is 20 times higher. As with many potentially malignant conditions, early diagnosis of cervical cancer can make all the difference in a patient’s life in terms of treatment outcomes. For this, developing effective, convenient, and easily available screening protocols for CIN and cervical cancer is of paramount importance.

Currently, the two ...

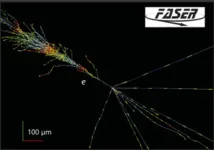

First measurement of electron- and muon-neutrino interaction rates at the highest energy ever detected from an artificial source

2024-08-05

Neutrinos are fundamental particles in the Standard Model of particle physics, notable for their extremely small masses and weak interactions with matter. They are important for answering fundamental questions about the universe, including why particles have mass and why there is more matter than antimatter. Despite being abundant, their weak interactions make their detection difficult, and hence they are called “ghost particles.” At any given moment, numerous neutrinos freely pass through the Earth and our bodies, which originate from the Sun or cosmic rays. Understanding their rare interactions with matter is crucial for obtaining a more complete picture ...

Breakthrough: Natural bacteria compound offers safe skin lightening

2024-08-05

Melanin protects the skin—the body's largest organ and a vital component of the immune system—from the damaging effects of ultraviolet (UV) radiation. When the skin is exposed to UV radiation, melanin production is stimulated in melanocytes, with tyrosinase playing a key role in the biosynthetic pathway. However, disruptions in this pathway caused by UV exposure or aging can lead to excess melanin accumulation, resulting in hyperpigmentation. To address this, tyrosinase inhibitors that suppress melanin synthesis have become valuable in the cosmetic industry. Unfortunately, some of these compounds, ...

Study analyzes potato-pathogen ‘arms race’ after Irish famine

2024-08-05

In an examination of the genetic material found in historic potato leaves, North Carolina State University researchers reveal more about the tit-for-tat evolutionary changes occurring in both potato plants and the pathogen that caused the 1840s Irish potato famine.

The study used a targeted enrichment sequencing approach to simultaneously examine both the plant’s resistance genes and the pathogen’s effector genes – genes that help it infect hosts – in a first-of-its-kind analysis.

“We use small pieces of historic leaves with the pathogen ...

Seismic detectors measure soil moisture using traffic noise

2024-08-05

Caltech researchers have developed a new method to measure soil moisture in the shallow subterranean region between the surface and underground aquifers. This region, called the vadose zone, is crucial for plants and crops to obtain water through their roots. However, measuring how this underground moisture fluctuates over time and between geographical regions has traditionally relied on satellite imaging, which only gives low-resolution averages and cannot penetrate below the surface. Additionally, moisture within the vadose zone changes rapidly—a thunderstorm can saturate a region that dries ...

State-level, out-of-pocket insulin caps do not substantially increase utilization, study finds

2024-08-05

AURORA, Colo. (August 5, 2024) – In a first-of-its-kind study, a cohort of researchers, led by the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, evaluated the effects of state-level insulin out-of-pocket costs across states and payers and over time. The team found that state-level caps on insulin out-of-pocket costs do not significantly increase insulin claims for patients with Type 1 or patients using insulin to manage Type 2 diabetes. Study results could help inform policies aimed at better delivering cost-capped insulin to patients struggling with insulin affordability.

Approximately ...

Preventing Parkinson’s disease may lie in seaweed antioxidants

2024-08-05

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease caused by the loss of neurons that produce dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved in motor control and cognitive function. As the global population ages, the number of Parkinson's disease patients is rapidly increasing. Parkinson's disease is induced by neuronal damage due to excessive production of reactive oxygen species.

Suppression of reactive oxygen species generation is essential because it is fatal to dopaminergic neurons that manage dopamine neurotransmitters. ...

Streetlights running all night makes leaves so tough that insects can’t eat them, threatening the food chain

2024-08-05

Light pollution disrupts circadian rhythms and ecosystems worldwide – but for plants, dependent on light for photosynthesis, its effects could be profound. Now scientists writing in Frontiers in Plant Science have found that exposure to high levels of artificial light at night makes tree leaves grow tougher and harder for insects to eat, threatening urban food chains.

“We noticed that, compared to natural ecosystems, tree leaves in most urban ecosystems generally show little sign of insect damage. We were curious as to why,” said corresponding author Dr Shuang Zhang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. “Here we show that in ...

Upfront mental health supports for men with prostate cancer

2024-08-04

Mental health screenings must be incorporated in routine prostate cancer diagnoses say University of South Australia researchers. The call follows new research that shows men need more supports both during and immediately after a diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Funded by Movember, the UniSA study tracked the scale and timing of mental health issues among 13,693 South Australian men with prostate cancer, finding that 15% of prostate cancer patients began mental health medications directly after a prostate cancer diagnosis, with 6% seeking help from mental health ...

Strengthening global regulatory capacity for equitable access to vaccines in public health emergencies

2024-08-03

WASHINGTON – Three high-impact steps could be taken by global health leaders to reshape the global regulatory framework and help address the pressing need for equitable access to diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines during public health emergencies, say a Georgetown global health law expert and a medical student.

In their “Perspective” published today in the New England Journal of Medicine, Georgetown School of Health professor Sam Halabi, JD, and George O’Hara, a Georgetown medical student and David E. Rogers Student ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

[Press-News.org] Heart transplant list doesn’t rank kids by medical need, Stanford Medicine-led study findsTransplant list not ranked by medical need