(Press-News.org) Many organisms react to the smell of deadly pathogens by reflexively avoiding them. But a recent study from the University of California, Berkeley, shows that the nematode C. elegans also reacts to the odor of pathogenic bacteria by preparing its intestinal cells to withstand a potential onslaught.

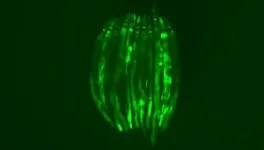

As with humans, nematodes’ guts are a common target of disease-causing bacteria. The nematode reacts by destroying iron-containing organelles called mitochondria, which produce a cell's energy, to protect this critical element from iron-stealing bacteria. Iron is a key catalyst in many enzymatic reactions in cells — in particular, the generation of the body's energy currency, ATP (adenosine triphophate).

The presence in C. elegans of this protective response to odors produced by microbes suggests that the intestinal cells of other organisms, including mammals, may also retain the ability to respond protectively to the smell of pathogens, said the study's senior author, Andrew Dillin, UC Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) investigator.

"Is there actually a smell coming off of pathogens that we can pick up on and help us fight off an infection?" he said. "We've been trying to show this in mice. If we can actually figure out that humans smell a pathogen and subsequently protect themselves, you can envision down the road something like a pathogen-protecting perfume."

So far, however, there's only evidence of this response in C. elegans. Nevertheless, the new finding is a surprise, considering that the nematode is one of the most thoroughly studied organisms in the laboratory. Biologists have counted and tracked every cell in the organism from embryo to death.

"The novelty is that C. elegans is getting ready for a pathogen before it even meets the pathogen," said Julian Dishart, who recently received his UC Berkeley Ph.D. and is the first author of the study. "There's also evidence that there's probably a lot more going on in addition to this mitochondrial response, that there might be more of a generalized immune response just by smelling bacterial odors. Because olfaction is conserved in animals, in terms of regulating physiology and metabolism, I think it's totally possible that smell is doing something similar in mammals as it's doing in C. elegans."

The work was published June 21 in the journal Science Advances.

Mitochondria communicate with one another

Dillin is a pioneer in studying how stress in the nervous system triggers protective responses in cells — in particular, the activation of a suite of genes that stabilize proteins made in the endoplasmic reticulum. This activation, the so-called unfolded protein response (UPR), is "like a first aid kit for the mitochondria," he said.

Mitochondria are not only the powerhouses of the cell, burning nutrients for energy, but also play a key role in signaling, cell death and growth.

Dillin has shown that errors in the UPR network can lead to disease and aging, and that mitochondrial stress in one cell is communicated to the mitochondria of cells throughout the body.

One key piece of the puzzle was missing, however. If the nervous system can communicate stress through a network of neurons to the cells doing the day-to-day work of protein building and metabolism, what in the environment triggers the nervous system?

"Our nervous system evolved to pick up on cues from the environment and create homeostasis for the entire organism," Dillin said. "Julian actually figured out that smell neurons are picking up environmental cues and which types of odorants from the pathogens turn on this response."

Previous work in Dillin's lab showed the importance of smell in mammalian metabolism. When mice are deprived of smell, he found, they gained less weight while eating the same amount of food as normal mice. Dillin and Dishart suspect that the smell of food may trigger a protective response, like the response to pathogens, in order to prepare the gut for the damaging effects of ingesting foreign substances and converting that food to fuel.

"Surviving infections was the most important thing we did evolutionarily," Dillin said. "And the most risky and taxing thing we do every single day is eat, because pathogens are going to be in our food."

"When you eat food, it's also incredibly stressful, because the body is metabolizing the food but also generating ATP in the mitochondria from the nutrients that they're incorporating. And that generation of ATP causes a by-product called reactive oxygen species, which is very damaging to cells," Dishart said. "Cells have to deal with this increased existence of reactive oxygen species. So perhaps smelling food can prepare us to deal with that enhanced reactive oxygen species load."

Dillin speculates further that mitochondria's sensitivity to the smell of pathogenic bacteria may be a holdover from an era when mitochondria were free-living bacteria, before they were incorporated into other cells as power plants to become eukaryotes some 2 billion years ago. Eukaryotes eventually evolved into multicellular organisms with differentiated organs — so-called metazoans, like animals and humans.

"There's a lot of evidence that bacteria sense their environment in some way, though it's not always clear how they do it. These mitochondria have retained one aspect of that after being subsumed into metazoans," he said.

In his experiments with C. elegans, Dishart found that the smell of pathogens triggers an inhibitory response, which unleashes a signal to the rest of the body. This became clear when he ablated olfactory neurons in the worm and found that all peripheral cells, but primarily intestinal cells, showed the stress response typical of mitochondria that are being threatened. This study and others also showed that serotonin is a key neurotransmitter communicating this information throughout the body.

Dillin and his lab colleagues are tracking the neural circuits that lead from smell neurons to peripheral cells and the neurotransmitters involved along the way. And he's looking for a similar response in mice.

"I always hate it when I get sick. I'm like, ‘Body, why didn't you prepare for this better?’ It seems really stupid that you turn on response mechanisms only once you're infected," Dillin said. "If there are earlier detection mechanisms to increase our chances of survival, I think that's a huge evolutionary win. And if we could harness that biomedically, that would be pretty wild."

Other UC Berkeley authors of the paper are Corinne Pender, Koning Shen, Hanlin Zhang, Megan Ly and Madison Webb. The work is supported by HHMI and the National Institutes of Health (R01ES021667, F32AG065381, K99AG071935).

END

Do smells prime our gut to fight off infection?

Nematodes react to the odor of pathogens by prepping their guts to withstand an infection. Do humans react similarly?

2024-08-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

mTORC1 in classical monocytes: Links to human size variation & neuropsychiatric disease

2024-08-07

"This report suggests that a simple assay may allow cost-effective prediction of medication response."

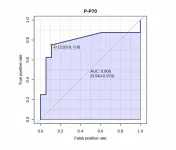

BUFFALO, NY- August 7, 2024 – A new research paper was published in Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as "Aging (Albany NY)" and "Aging-US" by Web of Science), Volume 16, Issue 14 on July 26, 2024, entitled, “mTORC1 activation in presumed classical monocytes: observed correlation with human size variation and neuropsychiatric disease.”

In this new study, researchers Karl Berner, Naci Oz, Alaattin Kaya, Animesh Acharjee, and Jon Berner ...

In Parkinson’s, dementia may occur less often, or later, than thought

2024-08-07

MINNEAPOLIS – There’s some good news for people with Parkinson’s disease: The risk of developing dementia may be lower than previously thought, or dementia may occur later in the course of the disease than previously reported, according to a study published in the August 7, 2024, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

“The development of dementia is feared by people with Parkinson’s, and the combination of both a movement disorder and a cognitive disorder can be devastating to them and their loved ones,” said study author Daniel Weintraub, MD, ...

Impact of drought on drinking water contamination: disparities affecting Latino/a communities

2024-08-07

Long-term exposure to contaminants such as arsenic and nitrate in water is linked to an increased risk of various diseases, including cancers, cardiovascular diseases, developmental disorders and birth defects in infants. In the United States, there is a striking disparity in exposure to contaminants in tap water provided by community water systems (CWSs), with historically marginalized communities at greater risks compared to other populations. Often, CWSs that distribute water with higher contamination levels exist in areas that lack adequate public infrastructure or sociopolitical and financial resources.

In ...

Pesticide exposure linked to stillbirth risk in new study

2024-08-07

Living less than about one-third of a mile from pesticide use prior to conception and during early pregnancy could increase the risk of stillbirths, according to new research led by researchers at the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health and Southwest Environmental Health Sciences Center.

Researchers found that during a 90-day pre-conception window and the first trimester of pregnancy, select pesticides, including organophosphates as a class, were associated with stillbirth.

The paper, “Pre-Conception ...

Individuals vary in how air pollution impacts their mood

2024-08-07

Affective sensitivity to air pollution (ASAP) describes the extent to which affect, or mood, fluctuates in accordance with daily changes in air pollution, which can vary between individuals, according to a study published August 7, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Michelle Ng from Stanford University, USA, and colleagues.

Individuals’ sensitivity to climate hazards is a central component of their vulnerability to climate change. Building on known associations between air pollution exposure and ...

Repetition boosts belief in climate-skeptical claims, even among climate science endorsers

2024-08-07

Climate science supporters rated climate-skeptical statements as “truer” after just a single repetition, according to a study published August 7, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE led by Mary Jiang from The Australian National University, Australia, and coauthored by Norbert Schwarz from the University of Southern California, USA, and colleagues. The results held true even for the strongest climate science supporters surveyed.

Amidst the influx of content that a person consumes each day, the principle of motivated ...

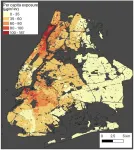

Study quantifies air pollution for NYC subway commuters

2024-08-07

New York City subway commuters who are economically disadvantaged or belong to racial minority groups have the highest exposure to fine particulate matter during their commutes, according to a new study published August 7, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Shams Azad of New York University, USA.

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is a type of air pollution that, due to its small size, when inhaled by a person can enter the bloodstream. PM2.5 is known to cause short- and long-term health complications. For the last few decades, cities have promoted public transportation to reduce traffic congestion and improve ambient outdoor air quality. Subway systems reduce pollution by decreasing ...

TikTok videos glamorizing disordered eating behavior and extremely thin body image ideals make women feel worse about their bodies

2024-08-07

Women who spend a lot of time on TikTok — especially those seeing a lot of pro-anorexia content — feel worse about their appearance, a new study shows. The results suggest that high TikTok exposure could harm mental health, reducing body image satisfaction and increasing the risk for disordered eating behavior. Madison Blackburn and Rachel Hogg from Charles Sturt University in Australia present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on August 7, 2024.

Since its launch, the short-form video app TikTok has had more than 2 billion downloads. The app’s algorithm curates content on a “For ...

Work-from-home success might depend on home office setup

2024-08-07

In a new survey study, Dutch employees who worked from home tended to report higher levels of productivity and less burnout if they were more satisfied with their home office setup. The study also linked more air ventilation in the home office to higher self-reported productivity. Martijn Stroom and colleagues at Maastricht University in the Netherlands report these findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on August 7, 2024.

In recent years, thanks in large part to the COVID-19 pandemic and technological advancements, ...

Trained dogs can sniff out CWD, a disease of major concern, in the droppings of farmed and wild deer, offering potential for non-invasive surveillance

2024-08-07

Trained dogs can sniff out CWD, a disease of major concern, in the droppings of farmed and wild deer, offering potential for non-invasive surveillance

###

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0303225

Article Title: Biodetection of an odor signature in white-tailed deer associated with infection by chronic wasting disease prions

Author Countries: USA

Funding: TWRA AP-14839 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and WILDLIFE RESOURCES AGENCY, TENNESSEE https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/business-services/financial-management-division/financial_services_branch/agreements_service_center/terms-conditions-for-aphis-awards ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

A Pitt-Johnstown professor found syntax in the warbling duets of wild parrots

Cleaner solar manufacturing could cut global emissions by eight billion tonnes

Safety and efficacy of stereoelectroencephalography-guided resection and responsive neurostimulation in drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy

Assessing safety and gender-based variations in cardiac pacemakers and related devices

New study reveals how a key receptor tells apart two nearly identical drug molecules

Parkinson’s disease triggers a hidden shift in how the body produces energy

Eleven genetic variants affect gut microbiome

Study creates most precise map yet of agricultural emissions, charts path to reduce hotspots

When heat flows like water

Study confirms Arctic peatlands are expanding

KRICT develops microfluidic chip for one-step detection of PFAs and other pollutants

How much can an autonomous robotic arm feel like part of the body

Cell and gene therapy across 35 years

Rapid microwave method creates high performance carbon material for carbon dioxide capture

New fluorescent strategy could unlock the hidden life cycle of microplastics inside living organisms

HKUST develops novel calcium-ion battery technology enhancing energy storage efficiency and sustainability

High-risk pregnancy specialists present research on AI models that could predict pregnancy complications

Academic pressure linked to increased risk of depression risk in teens

Beyond the Fitbit: Why your next health tracker might be a button on your shirt

UCSB scientists bottle the sun with liquid battery

Lung cancer drug offers a surprising new treatment against ovarian cancer

When consent meets reality: How young men navigate intimacy

Siemens Healthineers and Mayo Clinic expand strategic collaboration to enhance patient care through advanced technology

Physicists develop new protocol for building photonic graph states

OHSU-led research initiative examines supervised psilocybin

New review identifies pathways for managing PFAS waste in semiconductor manufacturing

New research finds state-level abortion restrictions associated with increased maternal deaths

New study assesses potential dust control options for Great Salt Lake

Science policy education should start on campus

Look again! Those wrinkly rocks may actually be a fossilized microbial community

[Press-News.org] Do smells prime our gut to fight off infection?Nematodes react to the odor of pathogens by prepping their guts to withstand an infection. Do humans react similarly?