(Press-News.org) A crowd or a flock of birds have different characteristics from those of atoms in a material, but when it comes to collective movement, the differences matter less than we might think. We can try to predict the behavior of humans, birds, or cells based on the same principles we use for particles. This is the finding of a new study published in the Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, JSTAT, conducted by an international team that includes the collaboration of MIT in Boston and CNRS in France. The study, based on the physics of materials, simulated the conditions that cause a sudden shift from a disordered state to a coordinated one in "self-propelled agents" (like biological ones).

“In a way, birds are flying atoms,” explains Julien Tailleur, from MIT Biophysics, one of the authors of the research. “It may sound strange, but indeed, one of our main findings was that the way a walking crowd moves, or a flock of birds in flight, shares many similarities with the physical systems of particles.”

As Tailleur explains, in the field of collective movement studies, it has been assumed that there is a qualitative difference between particles (atoms and molecules) and biological elements (cells, but also entire organisms in groups). It was especially believed that the transition from one type of movement to another (for example, from chaos to an orderly flow, known as a phase transition) was completely different.

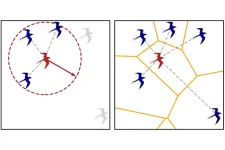

The crucial difference for physicists in this case has to do with the concept of distance. Particles moving in a space with many other particles influence each other primarily based on their mutual distance. For biological elements, however, the absolute distance is less important. “Take a pigeon flying in a flock: what matters to it are not so much all the closest pigeons, but those it can see.” In fact, according to the literature, among those it can see, it can only keep track of a finite number, due to its cognitive limits. The pigeon, in the physicists' jargon, is in a “topological relationship” with other pigeons: two birds could be at quite a large physical distance, but if they are in the same visible space, they are in mutual contact and influence each other.

It was long believed that this type of difference led to a completely different scenario for the emergence of collective motion “Our study, however, suggests that this is not a crucial difference,” continues Tailleur.

“Obviously, if we wanted to analyze the behavior of a real bird, there are tons of other complexities that are not included in our model. Our field follows an advice attributed to Einstein, namely that if you want to understand a phenomenon, you have to make it ‘as simple as possible, but not simpler’. Not the simplest possible, but the one that removes all complexity that is not relevant to the problem. In the specific case of our study, this means that the difference that is real and exists - between physical distance and topological relationship - does not alter the nature of the transition to collective motion.”

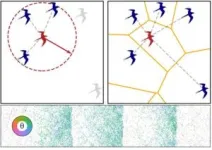

The model used by Tailleur and colleagues is inspired by the behavior of ferromagnetic materials. These materials have - as the name suggests - magnetic properties. At high temperature or low density, the spins (simplifying: the direction of the magnetic moment associated with electrons) are oriented randomly due to the large thermal fluctuations and are therefore disorderly. However, at low temperatures and high density, the interactions between the spins dominate the fluctuations and a global orientation of the spins emerges (imagining them as many aligned small compass needles).

“My colleague Hugues Chaté realized twenty years ago that, if the spins were to move in the direction in which they point, they would order through a discontinuous phase transition, with the sudden apparition of large groups of spins moving together, much like flocks of birds in the sky”, says Tailleur. This is very different from what happens in a passive ferromagnet, where the emergence of order occurs gradually. Until recently, physicists believed that biology-inspired models in which particles align with their `topological neighbors’ would also experience a continuous transition. In the model used in the study, Tailleur and colleagues showed that, instead, a discontinuous transition is observed, even if the topological relationship instead of distance is used, and that this scenario should apply to all such models. “Within some limits, the details of how you align is irrelevant”, says Tailleur, “and our work shows that this type of transition should be generic.”

Another finding is that in the model used, stratified flows form within the larger group, which is akin to what we also observe in reality: it is rare for a mass of people to move all together in one direction; rather, we see within it the motion of finite groups, distinguishable flows that follow slightly different trajectories.

These statistical models, based on the physics of particles, can therefore also help us understand biological collective movement, concludes Tailleur. “The road towards understanding collective motion as we see it in biology—and using it to design new materials—is still long, but we are making progress!”

END

Are birds flying atoms?

Physical and biological systems are different. But are they? A new study on JSTAT observes that similarities might be greater than we think

2024-08-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New study is helping to understand and achieve species elements in the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework

2024-08-08

Experts provide clarity on key terms for urgent species recovery actions to support the implementation of the Global Biodiversity Framework.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF) is a landmark agreement ratified in 2022 by Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity that outlines ambitious goals to combat biodiversity decline.

The Framework states outcomes for species to be achieved by 2050 in Goal A and establishes a range of targets to reduce pressures on biodiversity and halt biodiversity loss ...

Unlocking the secrets of salt stress tolerance in wild tomatoes

2024-08-08

As our climate changes and soil salinity increases in many agricultural areas, finding crops that can thrive in these challenging conditions is crucial. Cultivated tomatoes, while delicious, often struggle in salty soils. Their wild cousins, however, have evolved to survive in diverse and often harsh environments. A recent study delved into the genetic treasure trove of wild tomatoes to uncover secrets of salt tolerance that could be used to develop resilient crop varieties.

A team of researchers focused on Solanum pimpinellifolium, the closest wild relative of our beloved cultivated tomato. These tiny, ...

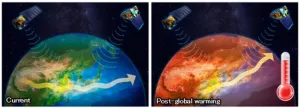

Detecting climate change using aerosols

2024-08-08

Climate change is one of the most significant environmental challenges of present times, leading to extreme weather events, including droughts, forest fires, and floods. The primary driver for climate change is the release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere due to human activities, which trap heat and raise Earth’s temperature. Aerosols (such as particulate matter, PM2.5) not only affect public health but also influence the Earth's climate by absorbing and scattering sunlight and altering cloud properties. Although future climate change predictions are being reported, it is possible that the impacts of climate change could be more severe than predicted. ...

Exploring the impact of attentional uniqueness and attentional allocation on firm growth

2024-08-08

According to the attention-based view, a firm’s actions and growth performance are directly influenced by its attentional allocation to specific issues. The consequences of organizational attention are reflected in the firm’s strategic decision-making and adaptability. However, existing literature is limited in its exploration of how a firm’s attentional uniqueness impacts its behavior and performance. Notably, attentional uniqueness refers to how the firm’s attentional allocation diverges from competitors in the same industry.

To address the above-mentioned knowledge gap, Associate Professor Takumi ...

Breakthrough in molecular control: new bioinspired double helix with switchable chirality

2024-08-08

The deoxyribonucleic acid or DNA, the molecular system that carries the genetic information of living organisms, can transcribe and amplify information using its two helical strands. Creating such artificial molecular systems that match or surpass DNA in functionality is of great interest to scientists. Double-helical foldamers are one such molecular system.

Helical foldamers are a class of artificial molecules that fold into well-defined helical structures like helices found in proteins and nucleic acids. They have garnered considerable attention as stimuli-responsive switchable molecules, tuneable chiral materials, and cooperative supramolecular systems due to their chiral and ...

Saliva indicates severity of recurrent respiratory infections in children

2024-08-08

A saliva test can more accurately indicate the severity of recurrent respiratory infections in children than the standard blood test. If saliva contains too few broadly protective antibodies, a child is more likely to suffer from pneumonia episodes. This is reported by researchers from Radboudumc Amalia Children's Hospital and UMC Utrecht Wilhelmina Children's Hospital in the European Respiratory Journal. Saliva testing provides valuable information for treatment and is more comfortable for children.

About ...

Short, intense bursts of exercise more effective after stroke than steady, moderate exercise

2024-08-08

Research Highlights:

Researchers found repeated one-minute bursts of high-intensity interval training were more effective than traditional, moderate continuous exercise for improving the body’s aerobic fitness after a stroke.

Fitness level improvements doubled in participants in the high-intensity interval training group compared to those in the moderate intensity exercise group.

Researchers found the level of fitness changes in the high intensity interval training group were associated with improved survival and lower risk of stroke-related ...

Imaging technique uncovers protein abnormality in motor neurone disease

2024-08-08

Pathological abnormalities associated with motor neurone disease have been identified using a new technique developed at the University of Birmingham.

The method will help scientists better understand the changes in the brain that lead to motor neurone disease (MND) and could eventually yield insights that will help with the development of new treatments. The abnormalities were identified in a collaboration between the University of Birmingham and the University of Sheffield and published today [8 Aug] in Nature Communications.

Motor neurone disease, also known ...

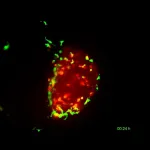

Scientists unravel how the BCG vaccine leads to the destruction of bladder cancer cells

2024-08-08

Using zebrafish “Avatars”, an animal model developed by the Cancer Development and Innate Immune Evasion lab at the Champalimaud Foundation (CF), led by Rita Fior, Mayra Martínez-López – a former PhD student at the lab now working at the Universidad de las Américas in Quito, Ecuador – and colleagues studied the initial steps of the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine’s action on bladder cancer cells. Their results, which are published today (August 1, 2024) in the journal Disease Models and Mechanisms, show that macrophages – the first line of ...

Cleveland Clinic study adds to increasing evidence that sugar substitute erythritol raises cardiovascular risk

2024-08-08

August 8, 2024, Cleveland: New Cleveland Clinic research shows that consuming foods with erythritol, a popular artificial sweetener, increases risk of cardiovascular events such as heart attack and stroke. The findings, from a new intervention study in healthy volunteers, show erythritol made platelets (a type of blood cell) more active, which can raise the risk of blood clots. Sugar (glucose) did not have this effect.

Published in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology, the research adds to increasing evidence that erythritol may not be as safe as currently ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Study reveals ancient needles and awls served many purposes

Key protein SYFO2 enables 'self-fertilization’ of leguminous plants

AI tool streamlines drug synthesis

Turning orchard waste into climate solutions: A simple method boosts biochar carbon storage

New ACP papers say health care must be more accessible and inclusive for patients and physicians with disabilities

Moisture powered materials could make cleaning CO₂ from air more efficient

Scientists identify the gatekeeper of retinal progenitor cell identity

American Indian and Alaska native peoples experience higher rates of fatal police violence in and around reservations

Research alert: Long-read genome sequencing uncovers new autism gene variants

Genetic mapping of Baltic Sea herring important for sustainable fishing

In the ocean’s marine ‘snow,’ a scientist seeks clues to future climate

Understanding how “marine snow” acts as a carbon sink

In search of the room temperature superconductor: international team formulates research agenda

Index provides flu risk for each state

Altered brain networks in newborns with congenital heart disease

Can people distinguish between AI-generated and human speech?

New robotic microfluidic platform brings ai to lipid nanoparticle design

COSMOS trial results show daily multivitamin use may slow biological aging

Immune cells play key role in regulating eye pressure linked to glaucoma

National policy to remedy harms of race-based kidney function estimation associated with increased transplants for Black patients

Study finds teens spend nearly one-third of the school day on smartphones, with frequent checking linked to poorer attention

Team simulates a living cell that grows and divides

Study illuminates the experiences of people needing to seek abortion care out of state

Digital media use and child health and development

Seeking abortion care across state lines after the Dobbs decision

Smartphone use during school hours and association with cognitive control in youths ages 11 to 18

Maternal acetaminophen use and child neurodevelopment

Digital microsteps as scalable adjuncts for adults using GLP-1 receptor agonists

Researchers develop a biomimetic platform to enhance CAR T cell therapy against leukemia

Heart and metabolic risk factors more strongly linked to liver fibrosis in women than men, study finds

[Press-News.org] Are birds flying atoms?Physical and biological systems are different. But are they? A new study on JSTAT observes that similarities might be greater than we think