(Press-News.org) (Santa Barbara, Calif.) — The body has a veritable army constantly on guard to keep us safe from microscopic threats from infections to cancer. Chief among this force is the macrophage, a white blood cell that surveils tissues and consumes pathogens, debris, dead cells, and cancer. Macrophages have a delicate task. It’s crucial that they ignore healthy cells while on patrol, otherwise they could trigger an autoimmune response while performing their duties.

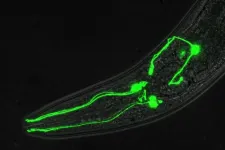

Researchers at UC Santa Barbara sought to understand how these immune cells choose what and when to eat. A paper published in Developmental Cell describes how the team programmed macrophages to respond to light in order to investigate how encounters with cancer cells change the macrophages’ appetite. “We discovered that giving macrophages an appetizer makes them hungrier for their next meal,” said senior author Meghan Morrissey, an assistant professor in the Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology.

The results present a new way to increase the effectiveness of cancer immunotherapies that harness macrophages to combat the disease. It also offers a more complex account of trained immunity, a kind of memory exhibited in the innate immune system that scientists have only recently recognized.

Using light to control the cellular appetite

While monitoring the body, macrophages scout for cells and debris tagged with the antibody IgG by other immune cells. These function as “eat me” signals to the macrophages, which detect them via Fc receptors (FcR) embedded in their cell membrane. Fc receptors are mobile, and begin to cluster once activated by IgG. Once this reaches a certain threshold, the macrophage engulfs the target.

Lead author Annalise Bond, a doctoral student in Morrissey’s lab, developed another way to cluster the FcR that doesn’t require IgG. With help from UCSB professor Max Willson, she designed a synthetic protein containing part of the FcR receptor fused to cryptochrome 2 (CRY2). This protein clusters together when activated by blue light, enabling Bond to precisely control the system and trigger the FcR at will.

The trick worked marvelously. Bond was able to use light to coax the macrophages to consume silica beads coated with a lipid membrane to mimic cancer cells. All without any IgG. Now they could give the macrophages a “light snack” to see how it affected their eating habits later on.

Pavlov’s macrophages

Bond stimulated engineered macrophages with light, then made the cells wait for different periods of time. She then presented them with the mock cancer cells, this time displaying that IgG “eat me” antibody.

The light-activated group ate much more after their simulated snack than the control group, which lacked light-activated FcR. “I’ve described it as Hungry Hungry Hippos,” Bond said, “because they’re just gobbling up everything that’s there.” Activating FcR with subthreshold levels of the IgG antibody on cancer cells also primed the macrophages for their next meal.

However, with too much stimulation, the effect disappeared. “If the macrophages got so much IgG that they actually eat, then it wasn’t an appetizer,” Morrissey explained. “It was more like a meal. So they weren’t hungry anymore.”

The authors aren’t positive why macrophages behave this way, but they have a hypothesis. As a macrophage scouts around healthy tissue, its top priority is to avoid triggering autoimmunity. So the macrophage sets a pretty high activation threshold. Now consider a macrophage that begins to encounter IgG antibodies. “Once you see a hint that something’s wrong, now your top priority is clearing the infection, and you’d be willing to damage the tissue a little bit if you had to,” Morrissey said.

What’s going on?

The macrophages’ appetite peaked around an hour after the initial trigger, before dipping and then rising again for a sustained period after four hours. Bond was curious what mechanisms underly this pattern. “One hour is way too fast for the cell to make new proteins,” Morrissey said, so something else must be going on.

Indeed, the macrophages retained their short-term priming when Bond blocked protein synthesis, suggesting that something else controlled this response. However, disabling protein synthesis eliminated the cells’ long-term enhanced appetite, indicating that this behavior relies on changes to gene expression and protein synthesis.

With more testing, Bond discovered that subthreshold activation of FcR triggered changes to how the receptors move around the cell membrane. It increases the receptors’ mobility, enabling them to aggregate more easily when exposed to IgG within about an hour. At the same time, the cell begins upregulating different genes and producing new proteins, explaining the longer term effects.

“This short-term mechanism is really interesting because it’s a totally different type of immune memory than what’s been seen before,” Morrissey said.

Hungry macrophages eat more cancer

Macrophages find antibodies like IgG irresistible; they’ll eat pretty much anything tagged with them, even the glass beads Bond used in her experiments. As a result, monoclonal antibodies have become a popular treatment for various diseases. In fact, antibodies are currently used in many different cancer therapies. Bond was able to increase the efficacy of a common antibody (Rituximab) that is used to treat lymphoma.

Bond and Morrissey’s results suggest that multiple, small doses of antibody therapy will be more effective than a single large dose, since previous doses can prime the cells for the next treatment. Indeed, oncologists found this to be true through trial and error.

There are also other macrophage therapies that might benefit from pretreatment: exposing engineered macrophages used in certain therapies to IgG before introducing them to the patient so they are primed to consume more cancer cells.

A memory spectrum

For a long time, biologists and doctors thought only the adaptive branch of the immune system had any sort of immunological memory. But a more nuanced picture has begun to emerge.

This experiment showed that even parts of the immune system that aren’t commonly thought of as having memory might respond to prompts. And it suggests that immunological memory is a spectrum, with some cells reacting to the here and now; others remembering infections for decades; and some, like macrophages, falling in between.

The work also presents a more complex portrayal of macrophages, suggesting that they’re more sophisticated decision makers than scientists had thought. “Macrophages need to think about the situation they’re in,” Morrissey said. “Are they in healthy tissue and need to avoid autoimmunity, or are they fighting an infection and need to go out guns blazing?”

Diving further into the details

Macrophages actually have two versions of the Fc receptor: One promotes their appetite while the other inhibits it. And both are triggered by IgG. Macrophages have more of the activating version, so that one eventually wins out. But it’s not clear why the cell has both, rather than just a smaller number of activating FcR.

It’s a mystery Bond is working to solve. “Now that I have this tool kit to explore macrophage appetite, I am really interested in understanding how the inhibitory FcR functions,” she said. The technique she developed enables her to selectively trigger just one FcR, so she might just be able isolate the role the inhibitory FcR plays in her future work.

END

An appetizer can stimulate immune cells’ appetite, a boon for cancer treatments

Macrophages exposed to low levels of 'eat me' antibodies consume more later

2024-08-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New genetically engineered wood can store carbon and reduce emissions

2024-08-12

Researchers at the University of Maryland genetically modified poplar trees to produce high-performance, structural wood without the use of chemicals or energy intensive processing. Made from traditional wood, Engineered wood is often seen as a renewable replacement for traditional building materials like steel, cement, glass and plastic. It also has the potential to store carbon for a longer time than traditional wood because it can resist deterioration, making it useful in efforts to reduce carbon emissions.

But the hurdle to true sustainability in engineered wood is that it requires processing with volatile chemicals and a significant amount of energy, and ...

NK cells expressing interleukin-21 show promising antitumor activity in glioblastoma cells

2024-08-12

Natural killer (NK) cells engineered to express interleukin-21 (IL-21) demonstrated sustained antitumor activity against glioblastoma stem cell-like cells (GSCs) both in vitro and in vivo, according to new research from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

The preclinical findings, published today in Cancer Cell, represent the first evidence that engineering NK cells, a type of innate immune cell, to secrete IL-21 resulted in strong activity against glioblastoma, a cancer type in need of more effective treatment options.

“Our ...

Strong insurance laws help kids get access to mental health care

2024-08-12

When states require insurers to cover mental and behavioral health, children get better access to care, according to a UC San Francisco-led study of nearly 30,000 U.S. caregivers.

They found that 1 in 8 caregivers had difficulty accessing mental health services for their children between 2016 and 2019. But those who lived in states with the most comprehensive mental and behavioral health coverage laws were about 20% less likely to report trouble accessing care than those who lived in states with the least comprehensive laws.

Caregivers of Black and Asian children were more likely to report poor access to mental and ...

State-of-the-art brain recordings reveal how neurons resonate

2024-08-12

For decades, scientists have focused on how the brain processes information in a hierarchical manner, with different brain areas specialized for different tasks. However, how these areas communicate and integrate information to form a coherent whole has remained a mystery. Now, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine have brought us closer to solving it by observing how neurons synchronize across the human brain while reading. The findings are published in Nature Human Behavior and are also the basis of a thesis by UC San Diego School of Medicine doctoral candidate Jacob Garrett.

“How the activity of the brain relates to the subjective ...

New study reveals unique histone tag in adult oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, opening doors for advanced myelin repair therapies

2024-08-12

NEW YORK, August 12, 2024 — In a groundbreaking study, researchers with the Advanced Science Research Center at the CUNY Graduate Center (CUNY ASRC) have identified a distinct histone tag in adult oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) that may pave the way for innovative therapies targeting myelin repair, a critical target for several neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders, including multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, and schizophrenia. The histone tag, characterized by lysine 8 acetylation on histone H4, identifies a significant departure from the histone modifications found in neonatal OPCs.

Detailed in a ...

SwRI launches Electrified Vehicle and Energy Storage Evaluation-II battery consortium

2024-08-12

SAN ANTONIO — August 12, 2024 – Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) is launching the next phase of an electric vehicle (EV) battery consortium dedicated to understanding performance of energy storage systems. The Electrified Vehicle and Energy Storage Evaluation-II (EVESE-II) consortium builds on more than a decade of SwRI-led, precompetitive research with companies across the mobility sector.

“We are proud to serve the EV industry by bringing together manufacturers, suppliers and battery designers and developers with materials scientists to address a variety of challenges,” said Dr. Andre Swarts, an SwRI staff engineer ...

Possible explanation for link between diabetes and Alzheimer's

2024-08-12

People with type 2 diabetes are at increased risk of Alzheimer's disease and other cognitive problems. A new study led by Umeå University, Sweden, shows that the reason may be that people with type 2 diabetes have more difficulty getting rid of a protein that may cause the disease.

"The results may be important for further research into possible treatments to counteract the risk of people with type 2 diabetes being affected by Alzheimer's," says Olov Rolandsson, senior professor at the Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine at Umeå University, research leader and first author of the study.

The substances ...

Surf spots are global ally in climate fight, study finds

2024-08-12

Surf Spots are Global Ally in Climate Fight, Study Finds

Nearly 90 million metric tonnes of planet-warming carbon found surrounding surf breaks across the world; U.S., Australia, Indonesia, Brazil identified as conservation priorities

ARLINGTON, Va. (Aug. 12, 2024) – A first-of-its-kind study, published today in Conservation Science and Practice, has found that the forests, mangroves and marshes surrounding surf breaks store almost 90 Mt (million metric tonnes) of climate-stabilizing “irrecoverable carbon,” making these coastal locations ...

Taking a ‘one in a million’ shot to tackle dopamine-linked brain disorders

2024-08-12

Dopamine, a powerful brain chemical and neurotransmitter, is a key regulator of many important functions such as attention, experiencing pleasure and reward, and coordinating movement. The brain tightly regulates the production, release, inactivation and signaling of dopamine via a host of genes whose identity and link to human disease continue to expand.

Brain disorders associated with altered dopamine signaling include substance use disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease. The complexity of the human brain and its ...

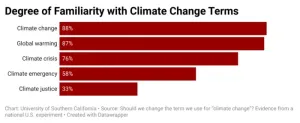

Just say “climate change” – not “climate emergency”

2024-08-12

The terms “climate change” and “global warming” are not only more familiar to people than some of their most common synonyms, but they also generate more concern about the warming of the Earth, according to a USC study published today in the journal Climatic Change.

The study began by looking at how familiar people are with the terms “global warming,” “climate change,” “climate crisis,” “climate emergency,” and “climate justice.” ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

[Press-News.org] An appetizer can stimulate immune cells’ appetite, a boon for cancer treatmentsMacrophages exposed to low levels of 'eat me' antibodies consume more later