The researchers will present their results at the fall meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS). ACS Fall 2024 is a hybrid meeting being held virtually and in person Aug. 18-22; it features about 10,000 presentations on a range of science topics.

When nanomaterial scientist Julie Vanegas joined the faculty at The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, she was paired with a faculty mentor, Teresa Patricia Feria Arroyo, an ecologist who works on solving problems related to food security and sustainability. During their early conversations, Vanegas mentioned that she’d been assessing recycled glass particles for coastal restoration projects, such as growing willow trees. Feria wondered if glass could also be used for growing produce. To answer Feria’s question, they developed experiments for growing foods that people are familiar with, mature quickly and can be cultivated in container and backyard gardens — the ingredients for pico de gallo.

“We’re trying to reduce landfill waste at the same time as growing edible vegetables,” says Andrea Quezada, a chemistry graduate student in the Nanoworld Vanegas lab who is presenting the team’s research at the meeting. “If this is viable, then we might be able to introduce glass-based soils into agricultural practices for people here in the Rio Grande Valley and across the country.”

For their experiments, the researchers get recycled glass particles from a company that diverts bottles from landfills, crushes them into particles and tumbles the pieces to round off the edges. The final product is smooth enough that people can handle the glass bits without getting cut, says Quezada. Similarly, plant roots can easily grow around the glass pieces without being harmed.

In initial tests, the researchers assessed the soil-like qualities, such as compaction and water retention, of three different sized glass fragments. They found that a size similar to coarse sand grains had characteristics, such as allowing oxygen to reach the roots and maintaining sufficient moisture levels, that could be ideal for plant cultivation.

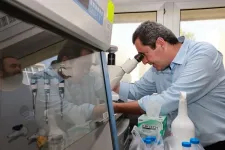

Now, Quezada is evaluating the recyclable glass material as a viable substitute for soil. In a greenhouse on campus, she’s growing cilantro, bell pepper and jalapeño plants in a variety of pots containing anywhere from 100% commercial potting soil to 100% recycled glass. Pots with more soil have higher levels of nutrients required for plant growth, including nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium, compared to those with more glass. But there’s little variation in pH level among the pots, which is a promising result because plants thrive in a narrow soil pH range.

Early results suggest that the plants grown in recyclable glass have faster growth rates and retain more water compared to those grown in 100% traditional soil. “A weight ratio of more than 50% of glass particles to soil appears best for plant growth compared to the other mixtures we tested,” says Vanegas. Though, the researchers are waiting until harvest time to confirm what soil mixture produces the highest yields — and tastiest produce.

Another noteworthy result is that pots with 100% potting soil developed a fungus that stunted plant growth. Feria hypothesizes the fungus may impact nutrient uptake by the roots. However, the pots that included any amount of recyclable glass didn’t have any fungal growth. The researchers are collecting data to determine why this might be.

These results are particularly promising to Quezada because the study was done without fertilizers, pesticides or fungicides. From her experience working in agriculture, she notes that a lot of the chemicals applied to the land impact people like her family members who work or live around farming communities. “I think it's really important to try to minimize the usage of any chemicals that can negatively affect our health,” says Quezada. “If we are able to reduce them, and help the community by collecting recyclables, then we can give people a better quality of life.”

The research was funded by an Empowering Future Agricultural Scientists grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, and a U.S. National Science Foundation grant that’s also supporting Glass Half Full, the company that supplied the glass particles.

A Headline Science video about this topic will be posted on Wednesday, Aug. 21. Reporters can access the videos during the embargo period, and once the embargo is lifted the same URLs will allow the public to access the content. Visit the ACS Fall 2024 program to learn more about this presentation, “Evaluating recyclable glass material as a substitute for soil in vegetable cultivation: An innovative approach to sustainable agriculture,” and other science presentations.

###

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS’ mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and all its people. The Society is a global leader in promoting excellence in science education and providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple research solutions, peer-reviewed journals, scientific conferences, eBooks and weekly news periodical Chemical & Engineering News. ACS journals are among the most cited, most trusted and most read within the scientific literature; however, ACS itself does not conduct chemical research. As a leader in scientific information solutions, its CAS division partners with global innovators to accelerate breakthroughs by curating, connecting and analyzing the world’s scientific knowledge. ACS’ main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

Registered journalists can subscribe to the ACS journalist news portal on EurekAlert! to access embargoed and public science press releases. For media inquiries, contact newsroom@acs.org.

Note to journalists: Please report that this research was presented at a meeting of the American Chemical Society. ACS does not conduct research, but publishes and publicizes peer-reviewed scientific studies.

Follow us: X, formerly Twitter | Facebook | LinkedIn | Instagram

Title

Evaluating recyclable glass material as a substitute for soil in vegetable cultivation: An innovative approach to sustainable agriculture

Abstract

Within environmental sustainability and ecological conservation, this research embarks into an innovative exploration of sustainable agricultural methodologies. It assesses the feasibility of using recyclable glass material as an alternative, coexistent, or complete replacement for conventional soil in cultivating specific vegetables, namely cilantro, bell pepper, and jalapeno. This initiative stems from growing concerns over the depletion of arable land and the pressing need for environmental preservation, leading to a meticulous exploration of alternative cultivation mediums. Central to this study is a comprehensive evaluation of recyclable glass materials' performance, efficacy, and safety for cultivating vegetables for human consumption. The research meticulously examines the availability of primary essential minerals in each growing medium, alongside factors such as environmental humidity and temperature, as well as the growth rate, yield, nutrient content, and contamination levels of vegetables cultivated in recyclable glass mediums, comparing them to those grown in conventional soil. Using recyclable glass as a cultivation medium presents intricate challenges, including optimizing glass particle size, refining nutrient delivery mechanisms, and enhancing moisture retention capabilities. Addressing these challenges is critical for improving this innovative agricultural method, increasing its adaptability, and maximizing operational efficiency. Developing suitable recyclable glass types specifically designed for agricultural use could significantly enhance the efficacy of this medium in vegetable cultivation. Continuous research and development in this scientific field are essential to overcome existing barriers and fully understand the potential of this eco-centric cultivation medium. This could strengthen the foundations of ecological conservation and advance global food security frontiers. The study's findings could revolutionize our approach to sustainable agriculture, offering a viable solution to soil depletion and contributing significantly to environmental preservation efforts.

END