(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio – Scientists have learned that children find it hard to focus on a task, and often take in information that won’t help them complete their assignment. But the question is, why?

In a new study, researchers found that this “distributed attention” wasn’t because children’s brains weren’t mature enough to understand the task or pay attention, and it wasn’t because they were easily distracted and lacked the control to focus.

It now appears that kids distribute their attention broadly either out of simple curiosity or because their working memory isn’t developed enough to complete a task without “over exploring.”

“Children can’t seem to stop themselves from gathering more information than they need to complete a task, even when they know exactly what they need,” said Vladimir Sloutsky, co-author of the study and professor of psychology at The Ohio State University.

Sloutsky conducted the study, published recently in the journal Psychological Science, with lead author Qianqian Wan, a doctoral student in psychology at Ohio State.

Sloutsky and his colleagues have done several studies in the past documenting how children distribute their attention broadly, and don’t seem to have the ability of adults to efficiently complete tasks by ignoring anything that is not relevant to their mission.

In this new research, Sloutsky and Wan confirmed that even when children successfully learn how to focus their attention on a task to earn small rewards such as stickers, they still “over explore” and don’t concentrate just on what is needed to complete their assignment.

One goal of this study was to see if children’s distractibility could be the explanation.

One study involved 4- to 6-year-old children and adults. Participants were told they were going to identify two types of bird-like creatures called Hibi or Gora. Each type had a unique combination of colors and shapes for their horn, head, beak, body, wing, feet and tail. For six of the seven body parts, the combination of color and shape predicted whether it was a Hibi or Gora with 66% accuracy. But one body part always was a perfect match to only one of the creatures, which both children and adults quickly learned to identify in the first part of the study.

In order to test whether children were easily distracted, the researchers covered up each body part, meaning the study participants had to uncover them one by one to identify which creature it was. They were rewarded for identifying the creature as quickly as possible.

For adults, the task was easy. If they knew the tail was the body part that was always matched perfectly with one of the two types of creatures, they always uncovered the tail and correctly identified the creature.

But the children were different. If they had learned the tail was the body part that always identified a creature perfectly, they would uncover that first – but they would still uncover other body parts before they made their choice.

“There was nothing to distract the children – everything was covered up. They could do like the adults and only click on the body part that identified the creature, but they did not,” Sloutsky said.

“They just kept uncovering more body parts before they made their choice.”

Another possibility is that children just like tapping on the buttons, Sloutsky said. So, in another study, they gave adults and children the opportunity to make just one tap on an “express” button to reveal the whole creature and all of its parts, or to tap on each body part individually to reveal it.

Children predominantly chose the express option to just tap once to reveal the creature to make their decision of what type it was. So, the kids weren’t just clicking for the fun of it.

Future studies will look at whether this unneeded exploration is simple curiosity, Sloutsky said. But he said he thinks the more likely explanation is that working memory is not fully developed in children. That means they don’t hold information they need to complete a task in their memory for very long, at least not as long as adults.

“The children learned that one body part will tell them what the creature is, but they may be concerned that they don’t remember correctly. Their working memory is still under development,” Sloutsky said.

“They want to resolve this uncertainty by continuing to sample, by looking at other body parts to see if they line up with what they think.”

As children’s working memory matures, they feel more confident in their ability to retain information for a longer time, he said, and act more like adults do.

The future research should resolve the question of whether the issue is curiosity or working memory, Sloutsky said.

This study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

END

Why children can’t pay attention to the task at hand

Researchers closer to understanding why kids ‘over explore’

2024-08-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

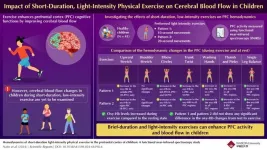

Short-duration, light-intensity exercises improve cerebral blood flow in children

2024-08-26

Cognitive functions, also known as intellectual functions, encompass thinking, understanding, memory, language, computation, and judgment, and are performed in the cerebrum. The prefrontal cortex (PFC), located in the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex, handles these functions. Studies have shown that exercise improves cognitive function through mechanisms such as enhanced cerebral blood flow, structural changes in the brain, and promotion of neurogenesis. However, 81% of children globally do not engage in enough physical activity, leading to high levels of sedentary behavior and insufficient exercise. This lack of physical ...

Exploring the role of cytochrome oxygenases in augmenting austocystin D-mediated cytotoxicity

2024-08-26

Austocystin D, a natural compound produced by fungi, has been recognized for its cytotoxic effects and anticancer activity in various cell types. It exhibits potent activity even in cells that express proteins associated with multidrug resistance, attracting significant global research interest. Austocystin D promotes cell death by damaging their DNA, a process which might be dependent on cytochrome P450 (CYP) oxygenase enzymes. Notably, austocystin D has shown significant activity against cancer cells with increased CYP expression. However, the specific role and function of the CYP2J2 enzyme in the cytotoxicity of austocystin D remain ...

Knowing you have a brain aneurysm may raise anxiety risk, other mental health conditions

2024-08-26

Research Highlights:

People diagnosed with unruptured cerebral aneurysms (weakened areas in brain blood vessels) who are being monitored without treatment have a higher risk of developing mental illness compared to those who have not been diagnosed with a cerebral aneurysm. The largest impact was among adults younger than age 40.

The study conducted in South Korea found that the psychological burden caused by the diagnosis of an unruptured aneurysm may contribute to the development of mental health conditions, such as anxiety, stress, depression, eating ...

Non-cognitive skills: the hidden key to academic success

2024-08-26

A new Nature Human Behaviour study, jointly led by Dr Margherita Malanchini at Queen Mary University of London and Dr Andrea Allegrini at University College London, has revealed that non-cognitive skills, such as motivation and self-regulation, are as important as intelligence in determining academic success. These skills become increasingly influential throughout a child's education, with genetic factors playing a significant role. The research, conducted in collaboration with an international team of experts, suggests that fostering non-cognitive skills alongside cognitive abilities could significantly improve educational ...

Finding love: Study reveals where love lives in the brain

2024-08-26

We use the word ‘love’ in a bewildering range of contexts — from sexual adoration to parental love or the love of nature. Now, more comprehensive imaging of the brain may shed light on why we use the same word for such a diverse collection of human experiences.

‘You see your newborn child for the first time. The baby is soft, healthy and hearty — your life’s greatest wonder. You feel love for the little one.’

The above statement was one of many simple scenarios presented to fifty-five parents, self-described as being in a loving relationship. Researchers from Aalto University utilised ...

Researchers develop high-entropy non-covalent cyclic peptide glass

2024-08-26

Researchers from the Institute of Process Engineering (IPE) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences have developed a sustainable, biodegradable, biorecyclable material: high-entropy non-covalent cyclic peptide (HECP) glass. This innovative glass features enhanced crystallization-resistance, improved mechanical properties, and increased enzyme tolerance, laying the foundation for its application in pharmaceutical formulations and smart functional materials. This study was published in Nature Nanotechnology on ...

Mapping the sex life of Malaria parasites at single cell resolution, reveals the genetics underlying Malaria transmission

2024-08-26

Malaria is caused by a eukaryotic microbe of the Plasmodium genus, and is responsible for more deaths than all other parasitic diseases combined. In order to transmit from the human host to the mosquito vector, the parasite has to differentiate to its sexual stage, referred to as the gametocyte stage. Unlike primary sex determination in mammals, which occurs at the chromosome level, it is not known what causes this unicellular parasite to form males and females. New research at Stockholm University has implemented high-resolution genomic tools to map the global repertoire of genes ...

Communicating consensus strengthens beliefs about climate change

2024-08-26

Climate scientists have long agreed that humans are largely responsible for climate change. However, people often do not realize how many scientists share this view. A new 27-country study published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour finds that communicating the consensus among scientists can clear up misperceptions and strengthen beliefs about climate change.

The study is co-led by Bojana Većkalov at the University of Amsterdam and Sandra Geiger of the University of Vienna. Kai Ruggeri, professor of health policy and management at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, is the corresponding author.

Scientific consensus identifying humans as primarily ...

Almost half of FDA-approved AI medical devices are not trained on real patient data

2024-08-26

Artificial intelligence (AI) has practically limitless applications in healthcare, ranging from auto-drafting patient messages in MyChart to optimizing organ transplantation and improving tumor removal accuracy. Despite their potential benefit to doctors and patients alike, these tools have been met with skepticism because of patient privacy concerns, the possibility of bias, and device accuracy.

In response to the rapidly evolving use and approval of AI medical devices in healthcare, a multi-institutional team of researchers at the UNC School of Medicine, Duke University, Ally Bank, Oxford University, Colombia University, and University of Miami have been on a mission to build ...

Does the extent of structural racism in a neighborhood affect residents’ risk of cancer from traffic-related air pollution?

2024-08-26

High levels of traffic-related air pollutants have been linked with elevated risks of developing cancer and other diseases. New research indicates that multiple aspects of structural racism—the ways in which societal laws, policies, and practices systematically disadvantage certain racial or ethnic groups—may contribute to increased exposure to carcinogenic traffic-related air pollution. The findings are published by Wiley online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

Most studies suggesting that structural racism, which encompasses factors such as residential segregation and differences in economic status and homeownership, may influence ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Cell and gene therapy across 35 years

Rapid microwave method creates high performance carbon material for carbon dioxide capture

New fluorescent strategy could unlock the hidden life cycle of microplastics inside living organisms

HKUST develops novel calcium-ion battery technology enhancing energy storage efficiency and sustainability

High-risk pregnancy specialists present research on AI models that could predict pregnancy complications

Academic pressure linked to increased risk of depression risk in teens

Beyond the Fitbit: Why your next health tracker might be a button on your shirt

UCSB scientists bottle the sun with liquid battery

Lung cancer drug offers a surprising new treatment against ovarian cancer

When consent meets reality: How young men navigate intimacy

Siemens Healthineers and Mayo Clinic expand strategic collaboration to enhance patient care through advanced technology

Physicists develop new protocol for building photonic graph states

OHSU-led research initiative examines supervised psilocybin

New review identifies pathways for managing PFAS waste in semiconductor manufacturing

New research finds state-level abortion restrictions associated with increased maternal deaths

New study assesses potential dust control options for Great Salt Lake

Science policy education should start on campus

Look again! Those wrinkly rocks may actually be a fossilized microbial community

Exposure to intense wildfire smoke during pregnancy may be linked to increased likelihood of autism

Children with Crohn’s have distinct gut bacteria from kids with other digestive disorders

Genomics offers a faster path to restoring the American chestnut

Caught in the act: Astronomers watch a vanishing star turn into a black hole

Why elephant trunk whiskers are so good at sensing touch

A disappearing star quietly formed a black hole in the Andromeda Galaxy

Yangtze River fishing ban halts 70 years of freshwater biodiversity decline

Genomic-informed breeding approaches could accelerate American chestnut restoration

How plants control fleshy and woody tissue growth

Scientists capture the clearest view yet of a star collapsing into a black hole

New insights into a hidden process that protects cells from harmful mutations

Yangtze River fishing ban halts seven decades of biodiversity decline

[Press-News.org] Why children can’t pay attention to the task at handResearchers closer to understanding why kids ‘over explore’