(Press-News.org) At the end of the Paleocene and beginning of the Eocene epochs, between 59 to 51 million years ago, Earth experienced dramatic warming periods, both gradual periods stretching millions of years and sudden warming events known as hyperthermals.

Driving this planetary heat up were massive emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases, but other factors like tectonic activity may have also been at play.

New research led by University of Utah geoscientists pairs sea surface temperatures with levels of atmospheric CO2 during this period, showing the two were closely linked. The findings also provide case studies to test carbon cycle feedback mechanisms and sensitivities critical for predicting anthropogenic climate change as we continue pouring greenhouse gases into the atmosphere on an unprecedented scale in the planet’s history.

“The main reason we are interested in these global carbon release events is because they can provide analogs for future change,” said lead author Dustin Harper, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Geology & Geophysics. “We really don't have a perfect analog event with the exact same background conditions and rate of carbon release.”

But the study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, or PNAS, suggests emissions during two ancient “thermal maxima” are similar enough with today’s anthropogenic climate change to help scientists forecast its consequences.

The research team analyzed microscopic fossils—recovered in drilling cores taken from an undersea plateau in the Pacific—to characterize surface ocean chemistry at the time the shelled creatures were alive. Using a sophisticated statistical model, they reconstructed sea surface temperatures and atmospheric CO2 levels over a 6-million-year period that covered two hyperthermals, the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, or PETM, 56 million years ago and Eocene Thermal Maximum 2, ETM-2, 54 million years ago.

The findings indicate that as atmospheric levels of CO2 rose, so too did global temperatures.

“We have multiple ways that our planet, that our atmosphere is being influenced by CO2 additions, but in each case, regardless of the source of CO2, we're seeing similar impacts on the climate system,” said co-author Gabriel Bowen, a U professor of geology & geophysics.

“We’re interested in how sensitive the climate system was to these changes in CO2. And what we see in this study is that there's some variation, maybe a little lower sensitivity, a lower warming associated with a given amount of CO2 change when we look at these very long-term shifts. But that overall, we see a common range of climate sensitivities.”

Today, human activities associated with fossil fuels are releasing carbon 4 to 10 times more rapidly than occurred during these ancient hyperthermal events. However, the total amount of carbon released during the ancient events is similar to the range projected for human emissions, potentially giving researchers a glimpse of what could be in store for us and future generations.

First scientists must determine what happened to the climate and oceans during these episodes of planetary heating more than 50 million years ago.

“These events might represent a mid- to worst-case scenario kind of case study,” Harper said. “We can investigate them to answer what’s the environmental change that happens due to this carbon release?”

Earth was very warm during the PETM. No ice sheets covered the poles and ocean temperatures in the mid-90s degrees Fahrenheit.

To determine oceanic CO2 levels the researchers turned to fossilized remains of foraminifera, a shelled single-cell organism akin to plankton. The research team based the study on cores previously extracted by the International Ocean Discovery Program at two locations in Pacific.

The foram shells accumulate small amounts of boron, the isotopes of which are a proxy reflecting CO2 concentrations in the ocean at the time the shells formed, according to Harper.

“We measured the boron chemistry of the shells, and we're able to translate those values using modern observations to past seawater conditions. We can get at seawater CO2 and translate that into atmospheric CO2,” Harper said. “The goal of the target study interval was to establish some new CO2 and temperature records for the PETM and ETM-2, which represent two of the best analogs in terms of modern change, and also provide a longer-term background assessment of the climate system to better contextualize those events.”

The cores Harper studied were extracted from Shatsky Rise in the subtropical North Pacific, which is an ideal location for recovering ocean-bottom sediments that reflect conditions in the ancient past.

Carbonate shells dissolve if they settle into deep ocean, so scientists must look to underwater plateaus like Shatsky Rise, where the water depths are relatively shallow. While their inhabitants were living millions of years ago, the foraminifera shells record the sea surface conditions.

“Then they die and sink to the sea floor, and they're deposited in about two kilometers of water depth,” Harper said. “We're able to retrieve the complete sequence of the dead fossils. At these places in the middle of the ocean, you really don't have a lot of sediment supply from continents, so it is predominantly these fossils and that's all. It makes for a really good archive for what we want to do.”

####

The study “Long- and short-term coupling of sea surface temperature and atmospheric CO2 during the late Paleocene and early Eocene,” was published Aug. 26 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, or PNAS. Funding came from National Science Foundation. The research was conducted in collaboration with colleagues at Columbia University, University of California Santa Cruz, Vassar College, Utah State University and University of Hawaii

END

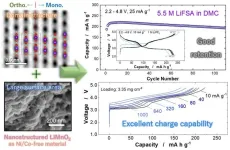

Lithium-ion (or Li-ion) batteries are heavy hitters when it comes to the world of rechargeable batteries. As electric vehicles become more common in the world, a high-energy, low-cost battery utilizing the abundance of manganese (Mn) can be a sustainable option to become commercially available and utilized in the automobile industry. Currently, batteries used for powering electric vehicles (EVs) are nickel (Ni) and cobalt (Co)-based, which can be expensive and unsustainable for a society with a growing desire for EVs. By switching the positive electrode ...

The Lundquist Institute for Biomedical Innovation at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center (TLI) announced updates to its Board of Directors today. TLI welcomes one new distinguished member and thanks the two outgoing members for their invaluable contributions.

“On behalf of the Board, I am delighted that Dr. Bill Dorfman, a global leader in cosmetic dentistry, has joined the TLI Board. Dr. Dorfman's extensive expertise and commitment to philanthropy make him an invaluable addition to our leadership,” said Mitchel Sayare, PhD, TLI Board ...

Parents who recently experienced intimate partner violence reported more parenting stress and higher potential for child maltreatment, and were less likely to use positive parenting strategies, according to UTHealth Houston research published Aug. 26, 2024, in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Our findings demonstrate the collateral damage of domestic violence — that the negative consequences are not limited to the couple and instead have the potential to affect how they parent, and ultimately the health of their children. We must expend every effort to prevent this public health problem,” said Jeff Temple, PhD, ...

How would you summarize your study for a lay audience?

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are cancer fighting drugs that help the immune system do its job of detecting and attacking tumor cells. Programmed Cell Death 1 (PD-1) is a common target for this type of drug—it is a protein that sits on the surface of T cells and helps regulate the immune system’s response to neighboring cells, both normal and cancerous. While most research efforts to date have focused on PD-1’s role in T cells, it is also active in many other kinds of cells—including cancer cells as first demonstrated by the Schatton ...

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Sandia National Laboratories and Arizona State University, two research powerhouses, are collaborating to push the boundaries of quantum technology and transform large-scale optical systems into compact integrated microsystems.

Nils Otterstrom, a Sandia physicist specializing in integrated photonics, is at the forefront of scaling down optical systems to the size of a chip. This innovation offers performance advantages and scalability for an array of applications from advanced computing to secure communications.

“Integrated ...

Nothing in science can be achieved or understood without measurement. Today, thanks to advances in quantum sensing, scientists can measure things that were once impossible to even imagine: vibrations of atoms, properties of individual photons, fluctuations associated with gravitational waves.

A quantum mechanical trick called “spin squeezing” is widely recognized to hold promise for supercharging the capabilities of the world’s most precise quantum sensors, but it’s been notoriously difficult to achieve. In new research, Harvard physicists describe how they’ve put spin squeezing ...

Colorado State University is leading a new interdisciplinary research project into the ways predators and prey in sensitive ecosystems may react to climate change based on their physiology, genetics and relationships to each other.

Led by Professor Chris Funk in the Department of Biology, the project is funded by the National Science Foundation’s Organismal Response to Climate Change program and will focus on interactions between cutthroat trout and tailed frogs in Pacific Northwest streams. This approach is one of the first times researchers have tried to test both the effects of evolution and ...

What:

The 2024 CBTN Summit hosted by the Children's Brain Tumor Network (CBTN) assembles the brightest minds in Pediatric Brian Tumor research for this annual conference. The event is free but attendees must register in advance.

Register at network.cbtn.org/cbtn-summit

Where:

In person at AWS Headquarters

Amazon WAS16 Aurora, 1770 Crystal Dr, Arlington, VA 22202

Virtual attendance available worldwide.

When:

October 9-11, 2024

Why:

This event is an opportunity ...

About The Study: Patients with post–COVID-19 mRNA vaccination myocarditis, contrary to those with post–COVID-19 myocarditis, show a lower frequency of cardiovascular complications than those with conventional myocarditis at 18 months. However, affected patients, mainly healthy young men, may require medical management up to several months after hospital discharge.

Corresponding Authors: To contact the corresponding authors, email Laura Semenzato, MSc (laura.semenzato@assurance-maladie.fr) and Mahmoud Zureik, MD, PhD (Mahmoud.ZUREIK@ansm.sante.fr).

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The ...

Figuring out the nature of dark matter, the invisible substance that makes up most of the mass in our universe, is one of the greatest puzzles in physics. New results from the world’s most sensitive dark matter detector, LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ), have narrowed down possibilities for one of the leading dark matter candidates: weakly interacting massive particles, or WIMPs.

LZ, led by the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), hunts for dark matter from a cavern nearly one mile underground at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in South Dakota. The experiment’s new results explore weaker dark matter interactions ...