(Press-News.org) CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – Researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have discovered a molecule that can make brain cells resistant to programmed cell death or apoptosis.

This molecule, a tiny strand of nucleotides called microRNA-29 or miR-29, has already been shown to be in short supply in certain neurodegenerative illnesses such as Alzheimer's disease and Huntington's disease. Thus, the discovery could herald a new treatment to prompt brain cells to survive in the wake of neurodegeneration or acute injury like stroke.

"There is the real possibility that this molecule could be used to block the cascade of events known as apoptosis that eventually causes brain cells to break down and die," said senior study author Mohanish Deshmukh, PhD, associate professor of cell and developmental biology.

The study, published online Jan. 18, 2011, in the journal Genes & Development, is the first to find a mammalian microRNA capable of stopping neuronal apoptosis.

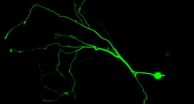

Remarkably, a large number of the neurons we are born with end up dying during the normal development of our bodies. Our nerve cells must span great distances to ultimately innervate our limbs, muscles and vital organs. Because not all nerve cells manage to reach their target tissues, the body overcompensates by sending out twice as many neurons as required. The first ones to reach their target get the prize, a cocktail of factors needed for them to survive, while the ones left behind die off. Once that brutal developmental phase is over, the remaining neurons become impervious to apoptosis and live long term.

But exactly what happens to suddenly keep these cells from dying has been a mystery. Deshmukh thought the key might lie in microRNAs, tiny but powerful molecules that silence the activity of as many as two-thirds of all human genes. Though microRNAs have been a hotbed of research in recent years, there have been relatively few studies showing that they play a role in apoptosis. So Deshmukh and his colleagues decided to look at all of the known microRNAs and see if there were any differences in young mouse neurons versus mature mouse neurons.

One microRNA jumped out at them, an entity called miR-29, which at that time had never before been implicated in preventing apoptosis. When the researchers injected their new molecule into young neurons, which are able to die if instructed, they found that the cells became resistant to apoptosis, even in the face of multiple death signals.

They then decided to pinpoint where exactly this molecule played a role in the series of biochemical events leading to cell death. The researchers looked at a number of steps in apoptosis and found that miR-29 acts at a key point in the initiation of apoptosis by interacting with a group of genes called the BH3-only family. Interestingly, the microRNA appears to interact with not just one but as many as five members of that family, circumventing a redundancy that existed to allow cell death to continue even if one of them had been blocked.

"People in the field have been perplexed that when they have knocked-out any one of these members it hasn't had a remarkable effect on apoptosis because there are others that can step in and do the job," said Deshmukh. "The fact that this microRNA can target multiple members of this family is very interesting because it shows how a single molecule can basically in one stroke keep apoptosis from happening. Interestingly, it only targets the members that are important for neuronal apoptosis, so it may be a way of specifically preserving cells in the brain without allowing them to grow out of control (and cause cancer) elsewhere in the body."

Deshmukh is currently developing mouse models where miR-29 is either "knocked-out" or overactive and plans to cross them with models of Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and ALS to see if it can prevent neurodegeneration. He is also actively screening for small molecule compounds that can elevate this microRNA and promote neuronal survival.

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Study co-authors were Adam J. Kole, a graduate student in Deshmukh's lab; Vijay Swahari, research technician; and Scott M. Hammond, PhD, associate professor of cell and developmental biology.

New molecule could save brain cells from neurodegeneration, stroke

2011-01-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Don't understand what the product is? Ask a woman

2011-01-19

A new study in the Journal of Consumer Research shows that women are better than men at figuring out unusual products when they're among competing items.

"A lot of times when we look at how consumers respond to innovative change in a product's physical form, we fail to consider that the context where they see the product plays a major role in how they evaluate and interpret it," write authors Theodore J. Noseworthy, June Cotte, and Seung Hwan (Mark) Lee (all University of Western Ontario).

The researchers examined consumer reactions to innovative products, like a car ...

Bus and tram passengers warned to keep their germs to themselves

2011-01-19

You are six times more likely to end up at the doctors with an acute respiratory infection (ARI) if you have recently used a bus or tram — but those who use buses or trams daily might well be somewhat protected compared with more occasional users.

These are the findings of a study carried out by experts at The University of Nottingham into the relationship between public transport and the risk of catching an ARI. Their findings have been published in the online Journal BMC Infectious Diseases.

Jonathan Van Tam, Professor of Health Protection in the School of Community ...

Discovery of a pulsating star that hosts a giant planet

2011-01-19

Recently published in an article of the Astronomy & Astrophysics journal, a group of researchers from the Institute of Space Sciences (IEEC-CSIC) at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona has discovered, for the first time, a delta Scuti pulsating star that hosts a hot giant transiting planet. The study was carried out by the PhD student, Enrique Herrero, the researcher Dr. Juan Carlos Morales, the exoplanet expert, Dr. Ignasi Ribas, and the amateur astronomer, Mr. Ramón Naves.

WASP-33 (also known as HD15082) is hotter, more massive than the Sun (1.5 Msun) and is located at ...

Create intimacy with consumers or donors: Ask for their input

2011-01-19

People feel closer to businesses and nonprofits that solicit their advice, but soliciting expectations can distance potential customers, according to a new study in the Journal of Consumer Research.

"Marketers and nonprofits alike regularly solicit input from customers or donors for myriad reasons, most notably to measure consumers' preferences, expectations, and satisfaction," write authors Wendy Liu (USCD) and David Gal (Northwestern University). Interactive media such as Facebook and Twitter are providing even greater opportunities for interaction with customers.

The ...

Why do our emotions get in the way of rational decisions about safety products?

2011-01-19

A new study in the Journal of Consumer Research explores why people reject things that can make them safer.

"People rely on airbags, smoke detectors, and vaccines to make them safe," write authors Andrew D. Gershoff (University of Texas at Austin) and Johnathan J. Koehler (Northwestern University School of Law). "Unfortunately, vaccines do sometimes cause disease and airbags sometimes injure or kill. But just because these devices aren't perfect doesn't mean consumers should reject them outright."

The authors found that people feel betrayed when they learn about the ...

Critique 029: What should we advise about alcohol consumption? A debate amongst scientists

2011-01-19

A Letter to the Editor entitled "What should we advise about alcohol consumption?" was recently published by Maurizio Ponz de Leon in Intern Emerg Med.1 Dr. de Leon argues that the message of health benefits of moderate drinking "seems to me hazardous and extremely dangerous to diffuse in the general population." His reasons included (1) many people may be unable to distinguish between low–moderate and high consumption of wine, beer or spirits, and alcohol metabolism may differ remarkably from one subject to another; (2) alcohol remains a frequent cause of car crash, ...

Self-control and choices: Why we take the easy path after exerting ourselves

2011-01-19

After a rough day at the office, you might opt for a convenient, pretty restaurant over one with a top-notch menu, according to a new study in the Journal of Consumer Research.

"If you've had a tough day at work, how will that affect the decisions you make, like where to eat, what to do, and what to buy?" ask authors Echo Wen Wan (University of Hong Kong) and Nidhi Agrawal (Northwestern University). Their research revealed that people who are tired from a demanding task will tend to pass up the most desirable choices and go for options that seem to have attractive low-level ...

Young couples can't agree on whether they have agreed to be monogamous

2011-01-19

CORVALLIS, Ore. – While monogamy is often touted as a way to protect against disease, young couples who say they have discussed monogamy can't seem to agree on what they decided. And a significant percentage of those couples who at least agreed that they would be monogamous weren't.

A new study of 434 young heterosexual couples ages 18-25 found that, in 40 percent of couples, only one partner says the couple agreed to be sexually exclusive. The other partner said there was no agreement.

Public health researchers Jocelyn Warren and Marie Harvey of Oregon State University ...

Loss of reflectivity in the Arctic doubles estimate of climate models

2011-01-19

CORVALLIS, Ore. – A new analysis of the Northern Hemisphere's "albedo feedback" over a 30-year period concludes that the region's loss of reflectivity due to snow and sea ice decline is more than double what state-of-the-art climate models estimate.

The findings are important, researchers say, because they suggest that Arctic warming amplified by the loss of reflectivity could be even more significant than previously thought.

The study was published online this week in Nature Geoscience. It was funded primarily by the National Science Foundation, with data also culled ...

New technology provides first view of DNA damage within entire human genome

2011-01-19

New technology providing the first view of DNA damage throughout the entire human genome developed by Cardiff University scientists could offer a valuable new insight into the development and treatment of conditions like cancer.

Professor Ray Waters, Dr Simon Reed and Dr Yumin Teng from Cardiff University's Department of Genetics, Haematology and Pathology have developed a unique way of measuring DNA damage frequency using tiny microarrays.

Using the new method Cardiff scientists can, for the first time, examine all 28,000 human genes where previous techniques have ...