(Press-News.org) A new study has revealed that islands are home to around one in three of the world’s plant species, despite covering just over five per cent of the Earth’s land surface.

Dr Julian Schrader, from Macquarie University’s School of Natural Sciences, led a team of a dozen researchers from Australia, Germany, Spain, USA, Greece and Japan in analysing data on more than 304,103 plants – essentially all species known to science worldwide – uncovering a treasure trove of island biodiversity.

The team found 94,052 species are native to islands. Of these, 63,280 are endemic –found nowhere else in the world – representing 21 per cent of global plant diversity.

The team’s research, published in Nature, provides the first comprehensive assessment of vascular plants native and endemic to marine islands worldwide.

Native plants naturally occur on an island, while endemic plants are found only on that specific island or group of islands and nowhere else in the world.

Vascular plants make up most plants on Earth and include trees, shrubs, herbs, ferns and grasses. They have a circulatory system, unlike non-vascular plants such as mosses and liverworts.

“This is the first time we have had such a complete understanding of which species are where, globally,” says Dr Schrader. “We can now explore the conservation status of some of our rarest plants and come up with distinct strategies to conserve them, such as identifying botanical gardens that could host rescue populations.”

The study found that only six per cent of islands supporting endemic species met a United Nations goal to protect 30 per cent of land and sea areas by 2030.

Hotbeds of island diversity

The study identified several centres of plant endemism – areas with high numbers of species found nowhere else. Nearly all are large, tropical islands with complex topography and a long history of isolation.

Topping the list is Madagascar, home to a staggering 9,318 endemic plant species. This African island nation is followed closely by New Guinea (8,793 endemic species), Borneo (5,765), Cuba (2,679) and New Caledonia (2,493).

“Large geographical distances, and climates and environments that differ from other archipelagos or mainland regions, lead to a high rate of evolution of new species, or ‘speciation’,” says Dr Schrader.

Such isolation has led to some remarkable examples of plant evolution; in Hawaii, 126 species of lobeliads trace their lineage back to a single colonisation event.

However, many plants that have evolved in isolation, developing unique adaptations to their original ecosystems, may be poorly equipped to compete with introduced species.

Climate change poses an additional threat. Rising sea levels and increased frequency of extreme weather events are potentially devastating for low-lying islands and their unique flora.

The team has created a standardised checklist of all known vascular plants occurring on islands, documenting their geographical and phylogenetic distribution and conservation risk.

The dataset also provides a crucial baseline for monitoring changes in island plant communities over time and could offer a roadmap for prioritising protection efforts.

“In French Polynesia, I was trying to find one of the rarest plants in the world, the flowering shrub called tiare apetahi (Sclerotheca raiateensis), with only a few individuals left in the wild,” says Dr Schrader.

The plant has large, fragrant flowers and holds an important place in local culture and stories, but has been over-harvested and devoured by rats. “Nobody has yet figured out how to grow this species in botanical gardens – so it might go extinct in the near future,” Dr Schrader says.

END

One in three plants call islands home

2024-10-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Challenging current understanding, study reveals rapid release of dopamine not needed for initiating movement

2024-10-16

The chemical messenger dopamine is an essential catalyst that fuels activities and behaviors ranging from movement to cognition and learning. However, neuroscientists have long debated whether these functions rely on rapid bursts of dopamine or on the neurochemical’s slower action.

A new study led by researchers at Harvard Medical School provides an answer.

The work, conducted in mice and published Oct. 16 in Nature, shows that initiating movement doesn’t require a rapid burst of dopamine but instead relies on slow activity of the chemical over time. By contrast, reward-oriented behaviors, related to ...

CSIRO research reveals marine heatwaves are underreported in the deep ocean

2024-10-16

While marine heatwaves (MHWs) have been studied at the sea surface for more than a decade, new research published today in Nature has found 80 per cent of MHWs below 100 metres are independent of surface events, highlighting a previously overlooked aspect of ocean warming.

The study was conducted by Australia’s national science agency CSIRO and the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

MHWs are prolonged temperature events that can cause severe damage to marine habitats, such as impacts to coral reefs and species displacement. These events are becoming more frequent due to global warming, with notable occurrences off Australia’s East ...

Meat without vegetables: How bacteria in our stomachs today can tell us what was on the menu for the first humans

2024-10-16

In a study published in Nature, Prof. Daniel Falush of the Shanghai Institute of Immunity and Infection (SIII) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Prof. Yoshio Yamaoka of Oita University, Japan, and Prof. Kaisa Thorell of Gothenberg University, Sweden uncovered fascinating new details about the long association of humans and our stomach bacteria.

Since its discovery in 1983, Helicobacter pylori has become notorious as the cause of around a million cases of stomach cancer a year as well as other life-threatening gastric diseases. The bacterium is ...

Protein interactions: Who is partying with whom and who is ruining the party?

2024-10-16

Inside cells, it's like in a packed dance club: hundreds are partying. Some keep to themselves, others make their way through the crowd, chatting to everyone they meet. Some just say a quick hello, others stay with their best friends. In this club, there are all kinds of different interactions between party-goers. The same is the case in cells with proteins.

Cells are filled with many different types of proteins that interact with each other and often work together in groups. These groups are called complexes ...

New biochar nanocomposite enhances detection of acetaminophen and uric acid in urine

2024-10-16

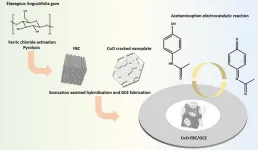

In recent years, the excessive use of acetaminophen (APAP) has become a significant human hazard and social burden. Rapid and automated electrochemical detection has emerged as a crucial method for measuring APAP concentration in human urine. This study explores a novel porous cobalt-derived biomass electrocatalyst material prepared from Elaeagnus angustifolia gum and investigates its electrochemical properties as well as its specific detection capability for APAP. Their work is published in the journal Industrial Chemistry & Materials on 18 July 2024.

Acetaminophen (APAP) is a commonly used analgesic and antipyretic ...

F. William Studier receives the 2024 Merkin Prize in ceremony at the Broad Institute for developing technology used to produce millions of doses of COVID-19 vaccines

2024-10-16

The 2024 Richard N. Merkin Prize in Biomedical Technology was awarded to F. William Studier of Brookhaven National Laboratory in a ceremony and symposium at the Broad Institute on September 17, 2024. The prize, created by the Merkin Family Foundation and administered by the Broad, recognizes novel technologies that have significantly improved human health and carries a $400,000 award. [Event Video]

Studier was announced as the winner in May for his development, in 1986, of an efficient, scalable method of producing ...

Applications open for School of Advanced Science on Structural Safety

2024-10-16

The “São Paulo School of Advanced Science on Structural Safety and its role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions by the built environment” will be held May 3-16, 2025, in Brazil, at the São Carlos School of Engineering of the University of São Paulo in its São Carlos campus.

Reporters are invited to register for the scientific sessions and short courses, which will present state-of-art science and results of new research.

This advanced science school will address the main challenges related to Structural Safety ...

Scientists use Allen Telescope Array to search for radio signals in the TRAPPIST-1 star system

2024-10-16

October 16, 2024, Mountain View, CA - Scientists at the SETI Institute and partners from Penn State University used the Allen Telescope Array (ATA) to search for signs of alien technology in the TRAPPIST-1 star system. The team spent 28 hours scanning the system, looking for radio signals that could indicate extraterrestrial technology. This project marks the longest single-target search for radio signals from TRAPPIST-1. Although they didn’t find any evidence of extraterrestrial technology, their work provided valuable data ...

Zebrafish as a model for studying rare genetic disease

2024-10-16

Fukuoka, Japan—Nager syndrome, or NS, is a rare genetic disease that affects the development of the face and limbs, usually causing anomalies in the bone structures of the jaws, cheeks, and hands. With a prevalence of less than 100 cases ever reported, not much is known about the disease except the fact that mutations in the SF3B4 gene are its primary cause. Now, in a recent study made available online on September 15, 2024 and upcoming in the November issue of International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, researchers from Kyushu University have developed a convenient approach to explore the underlying mechanisms ...

A synthetic molecular switch lets you 'paint' with natural light

2024-10-16

Liquid crystals exist in a phase of their own. They can flow like liquids, but because their molecules are arranged in a somewhat orderly way, they can be easily manipulated to reflect light. This flexibility has made liquid crystals the go-to material for energy-efficient phone, TV, and computer display screens.

In a new study in Nature Chemistry, researchers at Dartmouth and Southern Methodist University hint at other applications for liquid crystals that might one day be possible, all powered by natural light. They include liquid crystal ...