(Press-News.org)

A new University of Maryland-led discovery could spur the development of new and improved treatments for Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS), a rare genetic disorder with no known cure that causes accelerated aging in children.

Published in the journal Aging Cell on October 18, 2024, in collaboration with researchers from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Duke University, the study identified a protein linked to the cardiovascular health of animal models with progeria that could translate to human treatments. Heart failure and stroke are the most common causes of death for people with HGPS, who typically have a life expectancy between 6 and 20 years old.

These new findings from the lab of UMD Cell Biology and Molecular Genetics Professor Kan Cao are “highly promising,” according to lead author and biological sciences Ph.D. student Sahar Vakili.

“This could pave the way for new treatments targeting cardiovascular complications in HGPS, which are currently a major cause of mortality in the affected children,” Vakili said. “Beyond progeria, insights gained from this research might also be applicable to other age-related diseases where endothelial dysfunction plays a role.”

Sometimes called the “Benjamin Button disease,” HGPS causes a variety of symptoms associated with aging, including skin wrinkling, joint stiffness, and the loss of hair and body fat. The disease stems from a mutation in the LMNA (lamin A) gene, which produces a protein that helps to keep cells healthy.

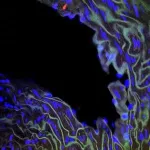

To better understand how progeria causes cardiovascular complications, the research team looked at endothelial cells. These cells line the body’s vascular system—including the heart—and control substances moving in and out of the bloodstream. When endothelial cells malfunction, it can lead to an array of conditions, including cardiovascular disease, stroke, blood clots and atherosclerosis (buildup of plaque inside the arteries).

More specifically, the researchers wanted to understand the signals sent by endothelial cells that ultimately lead to HGPS-related cardiovascular disease. For the first time, the team discovered that Angiopoietin-2 (Ang2)—a protein that regulates the formation of new blood vessels and the flow of substances through blood vessel walls—is significantly impaired in individuals with progeria, affecting the overall function of their endothelial cells.

The researchers discovered they could use Ang2 to “rescue” endothelial cells, improving their health despite dysfunction stemming from HGPS. It enhanced the formation of blood vessels, normalized cell migration and even restored nitric oxide levels, which are crucial for a healthy vascular system.

“Ang2 treatment also improves endothelial cell signaling to vascular smooth muscle cells, suggesting it could be a potential therapy for vascular dysfunctions in HGPS,” Vakili said.

Current treatments for HGPS can help reduce the risk of fatal complications like heart attack and stroke, but they do not target the underlying disease. Cao explained that their research is unlikely to offer a definitive progeria cure, but it could buy patients more time by improving their health in other ways.

“While Ang2 only has receptors on the endothelial cells, it may have a broader beneficial impact on additional tissue types beyond cardiovascular systems, such as bone and fat tissues, since blood vessels are essential for our body to transport nutrients, oxygen and waste,” said Cao, who started studying progeria during her postdoc in 2005, just two years after the cause of progeria was discovered.

As a next step, Cao plans to conduct a follow-up study in collaboration with a group at the NIH to explore different methods of administering Ang2 to animal models with progeria.

While the work is ongoing, Cao is confident that each new study will bring researchers closer to identifying a cure.

“We are getting really close to a cure for progeria,” she said. “Research-wise, we are pushing hard, and I can see the light at the end of the tunnel.”

###

In addition to Cao and Vakili, UMD co-authors included biological sciences graduate student Elizabeth Izydore (B.S. ’20, biological sciences), bioengineering undergraduate student Leonhard Losert and Huijing Xue (Ph.D. ’23, biological sciences).

Their paper, “Angiopoietin-2 reverses endothelial cell dysfunction in progeria vasculature,” was published in Aging Cellon October 18, 2024.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant Nos. HL138252 and HL126784 and the National Human Genome Research Institute intramural research fund). This article does not necessarily reflect the views of this organization.

END

By Dylan Walsh for UC Berkeley Haas

In the U.S., demand for in vitro fertilization (IVF) increased almost 140% between 2004 and 2018. Among other things, this trend suggests a business opportunity; in that same span of time the market share of for-profit chain clinics grew from 5% to 20%, with chains now performing over 40% of IVF treatment cycles nationwide.

“Chain organizations are very common in hotels and restaurants,” says Ambar La Forgia, an assistant professor at the Haas School of Business, UC Berkeley. “But when it comes to healthcare, because it hasn’t ...

A new UC Davis MIND Institute study offers critical insights into Rett syndrome, a rare genetic condition that affects mostly girls. The research reveals how this condition affects males and females differently, with symptoms progression linked to changes in gene responses in brain cells.

Rett syndrome is caused by mutations of the MECP2 gene located on the X chromosome. Children with Rett initially show typical development before symptoms start.

The symptoms vary widely. They include loss of hand function, breathing difficulties and seizures that affect the child’s ability to speak, walk, and eat. Rett is less common in males, ...

A multi-state study, published in The Lancet, is one of the first real world data analyses of the effectiveness of the RSV -- short for respiratory syncytial virus -- vaccine. VISION Network researchers report that across the board these vaccines were highly effective in older adults, even those with immunocompromising conditions, during the 2023-24 respiratory disease season, the first season after RSV vaccine approval in the U.S.

RSV vaccination provided approximately 80 percent protection against severe disease and hospitalization, Intensive Care Unit admission and death due to a respiratory infection as well as similar protection against less severe disease in adults ...

To forgive is to move on and set a foundation for a brighter future. In the workplace, forgiveness makes for healthier and more effective workgroups, especially when co-worker transgressions are minor and the need for effective collaboration is essential.

One's sense of masculinity, however, can impede an ability to forgive, a study led by UC Riverside associate professor of management Michael Haselhuhn has found.

The more men are concerned about appearing masculine, the less likely they will forgive a co-worker for a transgression such as missing an important meeting, ...

Research led by the University of Oxford has found that oceanographic connectivity (the movement and exchange of water between different parts of the ocean) is a key influence for fish abundance across the Western Indian Ocean (WIO). The findings have been published today in the ICES Journal of Marine Sciences.

Connectivity particularly impacted herbivorous reef fish groups, which are most critical to coral reef resilience, providing evidence that decision-makers should incorporate connectivity into how they prioritise conservation areas.

The study also revealed that, alongside oceanographic connectivity, sea surface temperature ...

The Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) in Woods Hole, Mass., has long been a magnet for scientific talent, as partly evidenced by the long list of Nobel laureates affiliated with the lab since 1929. Last week, the MBL was proud to add two new scientists to this list, which now includes 63 names:

* Gary Ruvkin, former co-director of the MBL Biology of Aging course, was co-recipient with Victor Ambros of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (for the discovery of microRNA and its role in gene regulation). here.

* John Hopfield, former faculty in the MBL Methods in Computational Neuroscience ...

Consuming more ultra-processed foods — from diet sodas to packaged crackers to certain cereals and yogurts — is closely linked with higher blood sugar levels in people with Type 2 diabetes, a team of researchers in nutritional sciences, kinesiology and health education at The University of Texas at Austin have found.

In a paper recently published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the team describes how — even more than just the presence of sugar and salt in the diet — having more ultra-processed ...

Hoboken, N.J. October 17, 2024 – When natural disasters strike, social networks like Facebook and X (formerly known as Twitter) can be powerful tools for public communication—but often, rescue workers and government officials struggle to make themselves heard above the general hubbub.

In fact, new research from the Stevens Institute of Technology shows, during four recent major hurricanes, important public safety messaging was drowned out by more trivial social content—including people tweeting about pets, sharing human-interest stories, or bickering about politics. That’s a big problem for officials working to understand where help is needed ...

With time being of the essence for patients facing one of cancer's most dire complications, UCLA researchers are working to create a new test to detect cancer’s spread to the central nervous system on the same day as the doctor’s visit.

When cancer spreads from its primary site, such as the lungs or breast, to the brain or spine, there are well-established methods of treating it. However, when these metastases spread to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), a condition known as leptomeningeal disease (LMD), median survival drops to around four ...

URBANA, Ill. — The foundation for healthy eating behavior starts in infancy. Young children learn to regulate their appetite through a combination of biological, psychological, and sociological factors. In a new paper, researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign propose a model that explores these factors and their interactions, providing guidelines for better understanding childhood appetite self-regulation.

“When we talk about obesity, the common advice is often to just eat less and exercise more. That’s a simplistic recommendation, which almost makes it seem ...