(Press-News.org) Billions of years ago, long before anything resembling life as we know it existed, meteorites frequently pummeled the planet. One such space rock crashed down about 3.26 billion years ago, and even today, it’s revealing secrets about Earth’s past.

Nadja Drabon, an early-Earth geologist and assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, is insatiably curious about what our planet was like during ancient eons rife with meteoritic bombardment, when only single-celled bacteria and archaea reigned – and when it all started to change. When did the first oceans appear? What about continents? Plate tectonics? How did all those violent impacts affect the evolution of life?

A new study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences sheds light on some of these questions, in relation to the inauspiciously named “S2” meteoritic impact of over 3 billion years ago, and for which geological evidence is found in the Barberton Greenstone belt of South Africa today. Through the painstaking work of collecting and examining rock samples centimeters apart and analyzing the sedimentology, geochemistry, and carbon isotope compositions they leave behind, Drabon’s team paints the most compelling picture to date of what happened the day a meteorite the size of four Mount Everests paid Earth a visit.

“Picture yourself standing off the coast of Cape Cod, in a shelf of shallow water. It’s a low-energy environment, without strong currents. Then all of a sudden, you have a giant tsunami, sweeping by and ripping up the sea floor,” said Drabon.

The S2 meteorite, estimated to have been up to 200 times larger than the one that killed the dinosaurs, triggered a tsunami that mixed up the ocean and flushed debris from the land into coastal areas. Heat from the impact caused the topmost layer of the ocean to boil off, while also heating the atmosphere. A thick cloud of dust blanketed everything, shutting down any photosynthetic activity taking place.

But bacteria are hardy, and following impact, according to the team’s analysis, bacterial life bounced back quickly. With this came sharp spikes in populations of unicellular organisms that feed off the elements phosphorus and iron. Iron was likely stirred up from the deep ocean into shallow waters by the aforementioned tsunami, and phosphorus was delivered to Earth by the meteorite itself and from an increase of weathering and erosion on land.

Drabon’s analysis shows that iron-metabolizing bacteria would thus have flourished in the immediate aftermath of the impact. This shift toward iron-favoring bacteria, however short-lived, is a key puzzle piece depicting early life on Earth. According to Drabon’s study, meteorite impact events – while reputed to kill everything in their wake (including, 66 million years ago, the dinosaurs) – carried a silver lining for life.

“We think of impact events as being disastrous for life,” Drabon said. “But what this study is highlighting is that these impacts would have had benefits to life, especially early on … these impacts might have actually allowed life to flourish.”

These results are drawn from the backbreaking work of geologists like Drabon and her students, hiking into mountain passes that contain the sedimentary evidence of early sprays of rock that embedded themselves into the ground and became preserved over time in the Earth’s crust. Chemical signatures hidden in thin layers rock help Drabon and her students piece together evidence of tsunamis and other cataclysmic events.

The Barberton Greenstone Belt in South Africa, where Drabon concentrates most of her current work, contains evidence of at least eight impact events including the S2. She and her team plan to study the area further to probe even deeper into Earth and its meteorite-enabled history.

END

What happened when a meteorite the size of four Mount Everests hit Earth?

Giant impacts had silver lining for life

2024-10-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Weather-changing El Niño oscillation is at least 250 million years old

2024-10-21

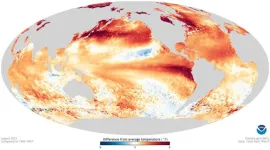

DURHAM, N.C. – The El Niño event, a huge blob of warm ocean water in the tropical Pacific Ocean that can change rainfall patterns around the globe, isn't just a modern phenomenon.

A new modeling study from a pair of Duke University researchers and their colleagues shows that the oscillation between El Niño and its cold counterpart, La Niña, was present at least 250 million years in the past, and was often of greater magnitude than the oscillations we see today.

These temperature swings were more intense in the past, and the oscillation occurred even when the continents were in different places than they are now, according to the study, which appears the week ...

Evolution in action: How ethnic Tibetan women thrive in thin oxygen at high altitudes

2024-10-21

Breathing thin air at extreme altitudes presents a significant challenge—there’s simply less oxygen with every lungful. Yet, for more than 10,000 years, Tibetan women living on the high Tibetan Plateau have not only survived but thrived in that environment.

A new study led by Cynthia Beall, Distinguished University Professor Emerita at Case Western Reserve University, answers some of those questions. The new research, recently published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), reveals how the Tibetan women’s physiological ...

Microbes drove methane growth between 2020 and 2022, not fossil fuels, study shows

2024-10-21

Microbes in the environment, not fossil fuels, have been driving the recent surge in methane emissions globally, according to a new, detailed analysis published Oct 28 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by CU Boulder researchers and collaborators.

“Understanding where the methane is coming from helps us guide effective mitigation strategies,” said Sylvia Michel, a senior research assistant at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research(INSTAAR) and a doctoral student in the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at CU Boulder. “We need to know more about those emissions to ...

Re-engineered, blue light-activated immune cells penetrate and kill solid tumors

2024-10-21

HERSHEY, Pa. — Immunotherapies that mobilize a patient’s own immune system to fight cancer have become a treatment pillar. These therapies, including CAR T-cell therapy, have performed well in cancers like leukemias and lymphomas, but the results have been less promising in solid tumors.

A team led by researchers from the Penn State College of Medicine has re-engineered immune cells so that they can penetrate and kill solid tumors grown in the lab. They created a light-activated switch that controls protein function associated with cell ...

Rapidly increasing industrial activities in the Arctic

2024-10-21

The Arctic is threatened by strong climate change: the average temperature has risen by about 3°C since 1979 – almost four times faster than the global average. The region around the North Pole is home to some of the world’s most fragile ecosystems, and has experienced low anthropogenic disturbance for decades. Warming has increased the accessibility of land in the Arctic, encouraging industrial and urban development. Understanding where and what kind of human activities take place is key to ensuring sustainable development in the region – for both people and the environment. Until now, a comprehensive assessment of this part of the world has ...

Scan based on lizard saliva detects rare tumor

2024-10-21

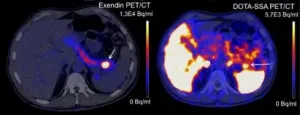

A new PET scan reliably detects benign tumors in the pancreas, according to research led by Radboud university medical center. Current scans often fail to detect these insulinomas, even though they cause symptoms due to low blood sugar levels. Once the tumor is found, surgery is possible.

The pancreas contains cells that produce insulin, known as beta cells. Insulin is a hormone that helps the body absorb sugar from the blood and store it in places like muscle cells. This regulates blood sugar levels. In rare cases, the beta cells malfunction, resulting in a benign tumor called ...

Rare fossils of extinct elephant document the earliest known instance of butchery in India

2024-10-21

During the late middle Pleistocene, between 300 and 400 thousand years ago, at least three ancient elephant relatives died near a river in the Kashmir Valley of South Asia. Not long after, they were covered in sediment and preserved along with 87 stone tools made by the ancestors of modern humans.

The remains of these elephants were first discovered in 2000 near the town of Pampore, but the identity of the fossils, cause of death and evidence of human intervention remained unknown until now.

A team ...

Argonne materials scientist Mercouri Kanatzidis wins award from American Chemical Society for Chemistry of Materials

2024-10-21

Mercouri Kanatzidis, a materials scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory and professor at Northwestern University, will receive the 2025 ACS Award in the Chemistry of Materials from the American Chemical Society, the nation’s leading professional organization of chemists.

The award “recognizes and encourages creative work in the chemistry of materials,” according to the citation.

At Argonne, Kanatzidis’s work has focused on the implications of a ...

Lehigh student awarded highly selective DOE grant to conduct research at DIII-D National Fusion Facility

2024-10-21

When it comes to sustainable energy, harnessing nuclear fusion is—for many—a holy grail of sorts. Unlike climate-warming fossil fuels, fusion offers a clean, nearly limitless source of energy by combining light atomic nuclei to form heavier ones, releasing vast amounts of energy in the process.

But it isn’t easy replicating and controlling the process that powers the sun.

“We eventually want to move to producing energy this way,” says Brian Leard ’21 ’25G, a ...

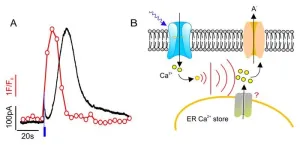

Plant guard cells can count environmental stimuli

2024-10-21

Plants control their water consumption via adjustable pores (stomata), which are formed from pairs of guard cells. They open their stomata when there is a sufficient water supply and enough light for carbon dioxide fixation through photosynthesis. In the dark and in the absence of water, however, they initiate the closing of the pores.

SLAC/SLAH-type anion channels in the guard cells are of central importance for the regulation of the stomata. This has been shown by the group of Professor Rainer Hedrich, biophysicist at Julius-Maximilians-Universität ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Globe-trotting ancient ‘sea-salamander’ fossils rediscovered from Australia’s dawn of the Age of Dinosaurs

Roadmap for Europe’s biodiversity monitoring system

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

[Press-News.org] What happened when a meteorite the size of four Mount Everests hit Earth?Giant impacts had silver lining for life