(Press-News.org) Capturing and storing the carbon dioxide humans produce is key to lowering atmospheric greenhouse gases and slowing global warming, but today's carbon capture technologies work well only for concentrated sources of carbon, such as power plant exhaust. The same methods cannot efficiently capture carbon dioxide from ambient air, where concentrations are hundreds of times lower than in flue gases.

Yet direct air capture, or DAC, is being counted on to reverse the rise of CO2 levels, which have reached 426 parts per million (ppm), 50% higher than levels before the Industrial Revolution. Without it, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, we won't reach humanity's goal of limiting warming to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) above preexisting global averages.

A new type of absorbing material developed by chemists at the University of California, Berkeley, could help get the world to negative emissions. The porous material — a covalent organic framework (COF) — captures CO2 from ambient air without degradation by water or other contaminants, one of the limitations of existing DAC technologies.

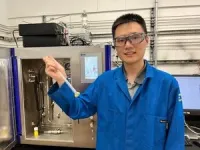

"We took a powder of this material, put it in a tube, and we passed Berkeley air — just outdoor air — into the material to see how it would perform, and it was beautiful. It cleaned the air entirely of CO2. Everything," said Omar Yaghi, the James and Neeltje Tretter Professor of Chemistry at UC Berkeley and senior author of a paper that will appear online Oct. 23 in the journal Nature.

"I am excited about it because there's nothing like it out there in terms of performance. It breaks new ground in our efforts to address the climate problem," he added.

According to Yaghi, the new material could be substituted easily into carbon capture systems already deployed or being piloted to remove CO2 from refinery emissions and capture atmospheric CO2 for storage underground.

UC Berkeley graduate student Zihui Zhou, the paper's first author, said that a mere 200 grams of the material, a bit less than half a pound, can take up as much CO2 in a year — 20 kilograms (44 pounds) — as a tree.

"Flue gas capture is a way to slow down climate change because you are trying not to release CO2 to the air. Direct air capture is a method to take us back to like it was 100 or more years ago," Zhou said. "Currently, the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere is more than 420 ppm, but that will increase to maybe 500 or 550 before we fully develop and employ flue gas capture. So if we want to decrease the concentration and go back to maybe 400 or 300 ppm, we have to use direct air capture."

COF vs MOF

Yaghi is the inventor of COFs and MOFs (metal-organic frameworks), both of which are rigid crystalline structures with regularly spaced internal pores that provide a large surface area for gases to stick or adsorb. Some MOFs that he and his lab have developed can adsorb water from the air, even in arid conditions, and when heated, release the water for drinking. He has been working on MOFs to capture carbon since the 1990s, long before DAC was on most people's radar screens, he said.

Two years ago, his lab created a very promising material, MOF-808, that adsorbs CO2, but the researchers found that after hundreds of cycles of adsorption and desorption, the MOFs broke down. These MOFs were decorated inside with amines (NH2 groups), which efficiently bind CO2 and are a common component of carbon capture materials. In fact, the dominant carbon capture method involves bubbling exhaust gases through liquid amines that capture the carbon dioxide. Yaghi noted, however, that the energy intensive regeneration and volatility of liquid amines hinders their further industrialization.

Working with colleagues, Yaghi discovered why some MOFs degrade for DAC applications — they are unstable under basic, as opposed to acidic, conditions, and amines are bases. He and Zhou worked with colleagues in Germany and Chicago to design a stronger material, which they call COF-999. Whereas MOFs are held together by metal atoms, COFs are held together by covalent carbon-carbon and carbon-nitrogen double bonds, among the strongest chemical bonds in nature.

As with MOF-808, the pores of COF-999 are decorated inside with amines, allowing uptake of more CO2 molecules.

"Trapping CO2 from air is a very challenging problem," Yaghi said. "It's energetically demanding, you need a material that has high carbon dioxide capacity, that's highly selective, that's water stable, oxidatively stable, recyclable. It needs to have a low regeneration temperature and needs to be scalable. It's a tall order for a material. And in general, what has been deployed as of today are amine solutions, which are energy intensive because they're based on having amines in water, and water requires a lot of energy to heat up, or solid materials that ultimately degrade with time."

Yaghi and his team have spent the last 20 years developing COFs that have a strong enough backbone to withstand contaminants, ranging from acids and bases to water, sulfur and nitrogen, that degrade other porous solid materials. The COF-999 is assembled from a backbone of olefin polymers with an amine group attached. Once the porous material has formed, it is flushed with more amines that attach to NH2 and form short amine polymers inside the pores. Each amine can capture about one CO2 molecule.

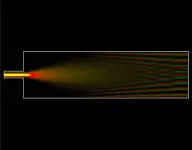

When 400 ppm CO2 air is pumped through the COF at room temperature (25 °C) and 50% humidity, it reaches half capacity in about 18 minutes and is filled in about two hours. However, this depends on the sample form and could be speeded up to a fraction a minute when optimized. Heating to a relatively low temperature — 60 °C, or 140 °F — releases the CO2, and the COF is ready to adsorb CO2 again. It can hold up to 2 millimoles of CO2 per gram, standing out from other solid sorbents.

Yaghi noted that not all the amines in the internal polyamine chains currently capture CO2, so it may be possible to enlarge the pores to bind more than twice as much.

"This COF has a strong chemically and thermally stable backbone, it requires less energy, and we have shown it can withstand 100 cycles with no loss of capacity. No other material has been shown to perform like that," Yaghi said. "It's basically the best material out there for direct air capture."

Yaghi is optimistic that artificial intelligence can help speed up the design of even better COFs and MOFs for carbon capture or other purposes, specifically by identifying the chemical conditions required to synthesize their crystalline structures. He is scientific director of a research center at UC Berkeley, the Bakar Institute of Digital Materials for the Planet (BIDMaP), which employs AI to develop cost-efficient, easily deployable versions of MOFs and COFs to help limit and address the impacts of climate change.

"We're very, very excited about blending AI with the chemistry that we've been doing," he said.

The work was funded by King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia, Yaghi's carbon capture startup, Atoco Inc., Fifth Generation's Love, Tito's, and BIDMaP. Yaghi's collaborators include Joachim Sauer, a visiting scholar from Humboldt University in Berlin, Germany, and computational scientist Laura Gagliardi from the University of Chicago.

END

Capturing carbon from the air just got easier

A new type of porous material called a covalent organic framework quickly sucks up CO2 from ambient air

2024-10-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Ultra-small spectrometer yields the power of a 1,000 times bigger device

2024-10-23

Spectrometers are technology for reading light that date back to the era of famed 17th-century physicist Isaac Newton. They work by breaking down light waves into their different colors — or spectra — to provide information about the makeup of the objects being measured.

UC Santa Cruz researchers are designing new ways to make spectrometers that are ultra-small but still very powerful, to be used for anything from detecting disease to observing stars in distant galaxies. Their inexpensive production cost makes them more accessible and customizable for specific applications.

The team of researchers, led by an interdisciplinary ...

Rocky planets orbiting small stars could have stable atmospheres needed to support life

2024-10-23

Since its launch in late 2021, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has raised the possibility that we could detect signs of life on exoplanets, or planets outside our solar system.

Top candidates in this search are rocky, rather than gaseous, planets orbiting low-mass stars called M-dwarfs — easily the most common stars in the universe. One nearby M-dwarf is TRAPPIST-1, a star about 40 light years away that hosts a system of orbiting planets under intense scrutiny in the search for life on planets orbiting stars other than the sun.

Previous research questioned the habitability of planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1, finding that intense UV rays would burn away their ...

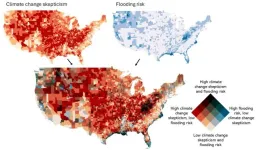

A 'worrying confluence' of flood risk, social vulnerability and climate change denial

2024-10-23

In certain parts of the United States, especially Appalachia, New England and the Northwest, the ability of residents to prepare for and respond to flooding is being undercut on three different levels.

This is according to a new study from the University of Michigan's School for Environment and Sustainability.

"It's a very worrying confluence that does keep me up," said Joshua Newell, a professor with the school's Center for Sustainable Systems and senior author of the study. "The communities that are most at risk of catastrophic flooding ...

Saving the bats: Researchers find bacteria, fungi on bat wings that could help fight deadly white-nose syndrome

2024-10-23

Saving the bats: Researchers find bacteria, fungi on bat wings that could help fight deadly white-nose syndrome

Hamilton, ON, Oct. 23, 2024 – Bacteria and fungi from the wings of bats could play a significant role in saving them from white-nose syndrome (WNS), a fungal disease affecting the skin of wings and muzzle, which has nearly wiped out vulnerable bat populations across North America.

Researchers at McMaster University have gathered and analyzed samples from the community of microorganisms, or microbiome, on the wings of several bat species ...

Project Cure CRC awards nearly $5 million in research funding

2024-10-23

Washington, D.C. – October 23, 2024 – Project Cure CRC, the breakthrough research fund of the leading nonprofit Colorectal Cancer Alliance (Alliance), has announced five new awardees of funds to advance urgent science in the colorectal cancer space. To date, 10 research grants have been awarded for a grand total of almost $5 million in critically needed funding.

Recipients of the most recent grants totaling almost $1 million include investigators from the University of California, San Francisco, Indiana University, University of Saskatchewan, Georgetown University, and Anglia Ruskin University. ...

New parasite discovered amid decline of California’s unique Channel Island fox

2024-10-23

California’s Channel Islands are home to the Channel Island fox (Urocyon littoralis), one of the smallest and most cherished species of island fox in the United States. Although no longer on the Endangered Species List, they remain a species of special concern due to their ecological importance.

In the 1990s, the San Miguel Island fox nearly went extinct, dropping to just 15 individuals. A recovery program restored their numbers by 2010. However, from 2014 to 2018, the population fell to 30% of its peak right after a new acanthocephalan parasite, commonly known as thorny-headed worms, was identified on the island. This also occurred while a multi-year draught heated San ...

Chemical Insights Research Institute publishes comprehensive guidance to protect community health impacted by wildland-urban interface fire events

2024-10-23

ATLANTA, Oct. 23, 2024 -- Chemical Insights Research Institute (CIRI) of UL Research Institutes has joined with UL Standards and Engagement to release new guidance for communities at risk for fires in wildland-urban interface (WUI) areas. An estimated 70,000 communities and 45 million residential buildings are at risk of destruction caused by wildfires. Additionally, WUI fires pose significant health risks. The smoke emitted by WUI fires likely contains a mixture of contaminants such as combustion gases, organic and inorganic metal complexes, volatile organic compounds and numerous reaction products. WUI wildfire plumes carry the risks of ...

New concussion sign identified by Mass General Brigham & Concussion Legacy Foundation scientists could identify up to 33% of undiagnosed concussions

2024-10-23

(Boston, MA) — Concussion researchers have recognized a new concussion sign that could identify up to 33% of undiagnosed concussions. After a hit to the head, individuals sometimes quickly shake their head back and forth. Although it has been depicted in movies, television, and even cartoons for decades, this motion has never been studied, named, and does not appear on any medical or sports organization’s list of potential concussion signs. A new study, led by Concussion Legacy Foundation (CLF) CEO and co-founder Chris Nowinski, PhD, says it should.

The study, published today in Diagnostics, reveals that when athletes exhibit this movement, ...

Dehydration linked to muscle cramps in IRONMAN triathletes

2024-10-23

PULLMAN, Wash. – As athletes prepare to dive into Hawaiian waters for the first part of the IRONMAN World Championship on Oct. 26, they may want to pay a little extra attention to the water inside their bodies.

Contrary to previous research, a Washington State University-led study of three decades of the IRONMAN’s top competition found a connection between dehydration and exercise-induced muscle cramps.

Based on medical data of more than 10,500 triathletes, the study, published in the Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, found a strong link between dehydration and participants seeking treatment for muscle cramps during the competition. ...

Study: Marshes provide cost-effective coastal protection

2024-10-23

Images of coastal houses being carried off into the sea due to eroding coastlines and powerful storm surges are becoming more commonplace as climate change brings a rising sea level coupled with more powerful storms. In the U.S. alone, coastal storms caused $165 billion in losses in 2022.

Now, a study from MIT shows that protecting and enhancing salt marshes in front of protective seawalls can significantly help protect some coastlines, at a cost that makes this approach reasonable to implement.

The new findings are being reported in the journal Communications ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

UCSB scientists bottle the sun with liquid battery

Lung cancer drug offers a surprising new treatment against ovarian cancer

When consent meets reality: How young men navigate intimacy

Siemens Healthineers and Mayo Clinic expand strategic collaboration to enhance patient care through advanced technology

Physicists develop new protocol for building photonic graph states

OHSU-led research initiative examines supervised psilocybin

New review identifies pathways for managing PFAS waste in semiconductor manufacturing

New research finds state-level abortion restrictions associated with increased maternal deaths

New study assesses potential dust control options for Great Salt Lake

Science policy education should start on campus

Look again! Those wrinkly rocks may actually be a fossilized microbial community

Exposure to intense wildfire smoke during pregnancy may be linked to increased likelihood of autism

Children with Crohn’s have distinct gut bacteria from kids with other digestive disorders

Genomics offers a faster path to restoring the American chestnut

Caught in the act: Astronomers watch a vanishing star turn into a black hole

Why elephant trunk whiskers are so good at sensing touch

A disappearing star quietly formed a black hole in the Andromeda Galaxy

Yangtze River fishing ban halts 70 years of freshwater biodiversity decline

Genomic-informed breeding approaches could accelerate American chestnut restoration

How plants control fleshy and woody tissue growth

Scientists capture the clearest view yet of a star collapsing into a black hole

New insights into a hidden process that protects cells from harmful mutations

Yangtze River fishing ban halts seven decades of biodiversity decline

Researchers visualize the dynamics of myelin swellings

Cheops discovers late bloomer from another era

Climate policy support is linked to emotions - study

New method could reveal hidden supermassive black hole binaries

Novel AI model accurately detects placenta accreta in pregnancy before delivery, new research shows

Global Physics Photowalk winners announced

Exercise trains a mouse's brain to build endurance

[Press-News.org] Capturing carbon from the air just got easierA new type of porous material called a covalent organic framework quickly sucks up CO2 from ambient air