(Press-News.org) Most people who visit a doctor when they feel unwell seek a diagnosis and a treatment plan. But for some 30 million Americans with rare diseases, their symptoms don’t match well-known disease patterns, sending families on diagnostic odysseys that can last years or even lifetimes.

But a cross-disciplinary team of researchers and physicians from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and colleagues from around the world has solved the mystery of a child with a rare genetic illness that did not fit any known disease. The team found a link between the child’s neurological symptoms and a genetic change that affects how proteins are properly folded within cells, providing the parents with a molecular diagnosis and identifying an entirely new type of genetic disorder.

The results, published Oct. 31 in the journal Science, have potential to help find new therapies for rare brain malformations.

“Many patients with severe, rare genetic disease remain undiagnosed despite extensive medical evaluation,” said Stephen Pak, PhD, a professor of pediatrics and a co-corresponding author on the study. “Our study has helped a family better understand their child’s illness, preventing further unnecessary clinical evaluations and tests. The findings also have made it possible to identify 22 additional patients with the same or overlapping neurological symptoms and genetic changes that affect protein folding, paving the way for even more diagnoses and, ultimately, potential treatments.”

According to Pak, about 10% of patients with suspected genetic disorders have a variant in a gene that has not yet been linked to a disease. His career has been focused on solving such medical mysteries.

Pak and author Tim Schedl, PhD, a professor of genetics and a co-director of the model organisms screening center at WashU Medicine, use tiny roundworms called C. elegans to assess whether specific genetic changes found in undiagnosed patients are responsible for their symptoms. With funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), they and a team of researchers at WashU Medicine have committed to solving more such cases.

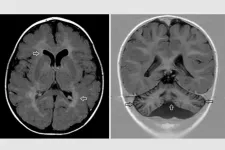

For this study, they teamed up with researchers and doctors from more than a dozen institutions across North America, Europe, India and China to identify the cause of a cluster of clinical findings in a boy from Germany, and other similar cases. The German patient had an intellectual disability, low muscle tone and a small brain with abnormal structures. Doctors also found changes to the CCT3 gene, so Pak’s team set out to determine if it could be the cause of the patient’s condition.

C. elegans has counterparts to about 50% of human genes, including the CCT3 gene, which is known as cct-3 in roundworms. Weimin Yuan, PhD, a staff scientist in pediatrics and co-first author, found that C. elegans with the patient’s genetic variant moved slower than roundworms with a healthy copy of the gene did, revealing that the genetic change can affect mobility and the nervous system.

The affected CCT3 protein is part of the large TRIC/CCT molecular complex whose job is to fold other proteins into their proper shape so they function as they should within cells. The study found that the protein-folding machinery cannot perform without a specific amount of healthy CCT3.

“We knew the child has one good and one bad variant gene copy,” Schedl said. “Our studies in C. elegans revealed that the genetic change reduces the activity of the normal protein, decreasing the capacity of the protein-folding machinery, and that for both C. elegans cct-3 and human CCT3, having 50% of activity was insufficient for normal biological function.”

The outcome of having reduced protein-folding machinery, they found, was that actin proteins – which help to maintain cell shape and movement –were incorrectly folded and abnormally distributed throughout the cells of C. elegans that carried the patient’s variant.

“An understanding of the impact of the genetic change informs the treatment modality,” Schedl added, “because the treatment needed to increase the amount of a normal protein differs from the treatment needed when the protein is poisonous or overactive.”

Collaborators from RWTH Aachen University in Germany and Stanford University performed complementary investigations into cct3 variants in zebrafish – which illuminated the effects of the gene on brain development – and in yeast, which clarified its role in protein folding, respectively.

To see if there are other patients out there with this same disorder, researchers mined a freely accessible global database of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. They identified 22 individuals with genetic changes in seven of the eight CCT proteins that form the protein-folding machine. Abnormalities in mobility and actin folding were again seen in roundworms with variants affecting CCT1 and CCT7 proteins, just as the WashU Medicine team observed with dysfunctional CCT3. Together, these patients represent a new type of rare genetic disease involving the protein folding machinery.

“This work underscores the importance of using simpler model organisms, like C. elegans, to provide novel insights into human pathobiology,” said co-author Gary Silverman, MD, PhD, the Harriet B. Spoehrer Professor of Pediatrics and head of the Department of Pediatrics.

“Our findings can inform clinicians, the scientific community, and patients and families all around the world that changes to the genetic message that are needed to make the eight-protein complex cause disease,” added Pak, who together with Schedl and a team of NIH-funded researchers at WashU Medicine, aim to solve challenging medical mysteries using advanced technologies. “If next week a patient with brain malformations and neurological symptoms is found to have a variant that affects the protein-folding machine, the patient will receive a diagnosis.”

Kraft F, Rodriguez-Aliaga P, Yuan W, Franken L, Zajt K, Hasan D, Lee TT, Flex E, Hentschel A, Innes AM, Zheng B, Suh DSJ, Knopp C, Lausberg E, Krause J, Zhang X, Trapane P, Carroll R, McClatchey M, Fry AE, Wang L, Giesselmann S, Hoang H, Baldridge D, Silverman GA, Radio FC, Enrico Bertini, Ciolfi A, Blood KA, de Sainte Agathe JM, Charles P, Bergant G, Cˇuturilo G, Peterlin B, Diderich K, Streff H, Robak L, Oegema R, van Binsbergen E, Herriges J,. Saunders CJ, Maier A, Wolking S, Weber Y, Lochmüller H, Meyer S, Aleman A, Polavarapu K, Nicolas G, Goldenberg A, Guyant L, Pope K, Hehmeyer KN, Monaghan KG, Quade A, Smol T, Caumes R, Duerinckx S, Depondt C, Paesschen WV, Rieubland C, Poloni C, Guipponi M, Arcioni S, Meuwissen M, Jansen AC, Rosenblum J, Haack TB, Bertrand M, Gerstner L, Magg J, Riess O, Schulz JB, Wagner N, Wiesmann M, Weis J, Eggermann T, Begemann M, Roos A, Häusler M, Schedl T, Tartaglia M, Bremer J, Pak SC, Frydman J, Elbrach M, Kurth I. Brain malformations and seizures by impaired chaperonin function of TRiC. Science. Oct. 31, 2024.

This work was support by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant number R01 HD110556; the NIH, grant numbers GM74074 and GM56433; the Children’s Discovery Institute, St Louis Children’s Hospital Foundation; Italian Ministry of Health, grant numbers RCR-2022-23682289 and PNRR-MR1-2022-12376811; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) for Foundation Grant, grant number FDN-167281; the Transnational Team Grant, grant number ERT-174211; the Network Grant OR2-189333, grant number NMD4C; the Canada Foundation for Innovation, grant number CFI-JELF 38412; the Canada Research Chairs program (Canada Research Chair in Neuromuscular Genomics and Health), grant number 950-232279; the European Commission, grant number 101080249; the Canada Research Coordinating Committee New Frontiers in Research Fund, grant number NFRFG-2022-00033and from the Government of Canada, Canada First Research Excellence Fund (CFREF) for the Brain-Heart Interconnectome, grant number CFREF-2022- 00007; CIHR Postdoctoral fellowship; the German Research Foundation, grant number WO 2385/2-1; the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation), grant numbers WE 1406/16-1, WE 1406/17-1, 418081722, 433158657, 499059538, INST 222/1458-1 FUGG, KU 1587/6-1, KU 1587/9-1, KU 1587/10-1 and KU 1587/11-1; the “Ministerium für Kultur und Wissenschaft des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen”, grant number PROFILNRW-2020–107-A; “Der Regierende Bürgermeister von Berlin, Senatskanzlei Wissenschaft und Forschung”; postdoctoral fellowship from The Hereditary Disease Foundation (2019-2023); the lonGER consortium; the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the EJP RD COFUND-EJP, grant number 825575. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the NIH.

About Washington University School of Medicine

WashU Medicine is a global leader in academic medicine, including biomedical research, patient care and educational programs with 2,900 faculty. Its National Institutes of Health (NIH) research funding portfolio is the second largest among U.S. medical schools and has grown 56% in the last seven years. Together with institutional investment, WashU Medicine commits well over $1 billion annually to basic and clinical research innovation and training. Its faculty practice is consistently within the top five in the country, with more than 1,900 faculty physicians practicing at 130 locations and who are also the medical staffs of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals of BJC HealthCare. WashU Medicine has a storied history in MD/PhD training, recently dedicated $100 million to scholarships and curriculum renewal for its medical students, and is home to top-notch training programs in every medical subspecialty as well as physical therapy, occupational therapy, and audiology and communications sciences.

END

Researchers solve medical mystery of neurological symptoms in kids

Study identifies genes that cause rare, undiagnosed brain malformations

2024-10-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Finding a missing piece for neurodegenerative disease research

2024-10-31

Research led by the University of Michigan has provided compelling evidence that could solve a fundamental mystery in the makeup of fibrils that play a role in Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and other neurodegenerative diseases.

"We've seen that patients have these fibril structures in their brains for a long time now," said Ursula Jakob, senior author of the new study. "But the questions are what do these fibrils do? What is their role in disease? And, most importantly, can we do something to get rid of them if they are responsible for these devastating diseases?"

Although the new finding does not explicitly answer those questions, it may provide a missing ...

Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine ranked in global top ten medical journals

2024-10-31

Notes to editors

For further information please contact:

Karen Nower

Media Office, Royal Society of Medicine

M: +44 (0)7587 084402

E: media@rsm.ac.uk

The Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine (JRSM) has been ranked as one of the world’s top ten general medicine journals for the first time.

Being placed tenth out of 329 ‘general and internal medicine’ titles in Clarivate’s 2023 Journal Citation Reports (JCR), this is JRSM’s highest ever ranking to date, having risen yearly ...

A new piece in the grass pea puzzle - updated genome sequence published

2024-10-31

An international research collaboration has completed the most detailed genome assembly to date of grass pea (Lathyrus sativus).

This new chromosome-scale reference genome published in Scientific Data offers new potential to accelerate modern breeding of this underutilised legume for climate-smart agriculture.

Nearly twice the size of the human genome, the sequence was assembled from scratch and improves on an earlier draft assembly of the vigorous grass pea line LS007.

“We ...

“Wearable” devices for cells

2024-10-31

CAMBRDIGE, MA – Wearable devices like smartwatches and fitness trackers interact with parts of our bodies to measure and learn from internal processes, such as our heart rate or sleep stages.

Now, MIT researchers have developed wearable devices that may be able to perform similar functions for individual cells inside the body.

These battery-free, subcellular-sized devices, made of a soft polymer, are designed to gently wrap around different parts of neurons, such as axons and dendrites, without damaging the cells, upon wireless actuation with light. By snugly wrapping neuronal processes, they could be used to measure ...

Cancer management: Stent sensor can warn of blockages in the bile duct

2024-10-31

Images

Stents to treat various blockages in the human body can themselves become blocked, but a new sensor developed at the University of Michigan for stents that are used in the bile duct may one day help doctors detect and treat stent blockages early, helping keep patients healthier.

Bile duct blockages can cause jaundice, liver damage and potentially life-threatening infections. Conditions that cause the bile ducts to narrow and close, including pancreatic and liver ...

Nov. 14 AARP Author Q&A at GSA 2024 in Seattle: Debra Whitman, Global Aging Expert and Author of ‘The Second Fifty: Answers to the 7 Big Questions of Midlife and Beyond’

2024-10-31

Author Q&A: Debra Whitman, Global Aging Expert and Author of “The Second Fifty”

Date: Thursday, November 14

Time: 4:30 to 5:30 p.m. PT

Location: Seattle Convention Center Arch Building Room 305

Registration: GSA 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting media registration is required to attend this event.

During this meet-the-author media roundtable, Debra Whitman, executive vice president and chief public policy officer at AARP, will discuss her new book, “The Second Fifty: Answers to the 7 Big ...

Autistic psychiatrists who don't know they're autistic may fail to spot autism in patients

2024-10-31

Groundbreaking research exploring the experiences of autistic psychiatrists has revealed that psychiatrists who are unaware that they themselves are autistic may fail to recognise the condition in their patients. The study, conducted by researchers from University College Dublin, London South Bank University, Brighton and Sussex Medical School, is the first of its kind to delve into the lives of neurodivergent psychiatrists. It was published today in BJPsych Open.

"Knowing that you are autistic can be positively life-changing," said the study author Dr Mary Doherty, Clinical Associate ...

New findings on animal viruses with potential to infect humans

2024-10-31

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Scientists investigating animal viruses with potential to infect humans have identified a critical protein that could enable spillover of a family of organisms called arteriviruses.

In a new study, researchers identified a protein in mammals that welcomes arteriviruses into host cells to start an infection. The team also found that an existing monoclonal antibody that binds to this protein protects cells from viral infection.

Arteriviruses circulate broadly in many types of mammals around the world that serve as natural hosts – such as ...

Ancient rocks may bring dark matter to light

2024-10-31

The visible universe — all the potatoes, gas giants, steamy romance novels, black holes, questionable tattoos, and overwritten sentences — accounts for only 5 percent of the cosmos.

A Virginia Tech-led team is hunting for the rest of it, not with telescopes or particle colliders, but by scrutinizing billion-year-old rocks for traces of dark matter.

In leading a transdisciplinary team from multiple universities on this unconventional search, physics’ Patrick Huber is also taking an unconventional step: from theoretical work into experimental work.

With support from a $3.5 million Growing Convergence Research ...

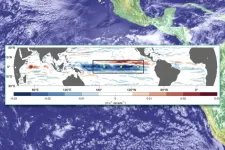

Study reveals acceleration in Pacific upper-ocean circulation over past 30 years, impacting global weather patterns

2024-10-31

A new study published October 31, 2024, in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans has revealed significant acceleration in the upper-ocean circulation of the equatorial Pacific over the past 30 years. This acceleration is primarily driven by intensified atmospheric winds, leading to increased oceanic currents that are both stronger and shallower, with potential impacts on regional and global climate patterns, including the frequency and intensity of El Niño and La Niña events. The study provides a spatial view of these long-term trends from observations, adding at least ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

Calibr-Skaggs and Kainomyx launch collaboration to pioneer novel malaria treatments

JAX-NYSCF Collaborative and GSK announce collaboration to advance translational models for neurodegenerative disease research

Classifying pediatric brain tumors by liquid biopsy using artificial intelligence

Insilico Medicine initiates AI driven collaboration with leading global cancer center to identify novel targets for gastroesophageal cancers

Immunotherapy plus chemotherapy before surgery shows promise for pancreatic cancer

A “smart fluid” you can reconfigure with temperature

New research suggests myopia is driven by how we use our eyes indoors

Scientists develop first-of-its-kind antibody to block Epstein Barr virus

With the right prompts, AI chatbots analyze big data accurately

Leisure-time physical activity and cancer mortality among cancer survivors

Chronic kidney disease severity and risk of cognitive impairment

Research highlights from the first Multidisciplinary Radiopharmaceutical Therapy Symposium

New guidelines from NCCN detail fundamental differences in cancer in children compared to adults

[Press-News.org] Researchers solve medical mystery of neurological symptoms in kidsStudy identifies genes that cause rare, undiagnosed brain malformations