(Press-News.org) Key takeaways

According to Bredt's rule, double bonds cannot exist at certain positions on organic molecules if the molecule's geometry deviates too far from what we learn in textbooks.

This rule has constrained chemists for a century.

A new paper in Science shows how to make molecules that violate Bredt’s rule, allowing chemists to find practical ways to make and use them in reactions.

UCLA chemists have found a big problem with a fundamental rule of organic chemistry that has been around for 100 years — it’s just not true. And they say: It’s time to rewrite the textbooks.

Organic molecules, those made primarily of carbon, are characterized by having specific shapes and arrangements of atoms. Molecules known as olefins have double bonds, or alkenes, between two carbon atoms. The atoms, and those attached to them, ordinarily lie in the same 3D plane. Molecules that deviate from this geometry are uncommon.

The rule in question, known as Bredt’s rule in textbooks, was reported in 1924. It states that molecules cannot have a carbon-carbon double bond at the ring junction of a bridged bicyclic molecule, also known as the “bridgehead” position. The double bond on these structures would have distorted, twisted geometrical shapes that deviate from the rigid geometry of alkenes taught in textbooks. Olefins are useful in pharmaceutical research, but Bredt’s rule has constrained the kind of synthetic molecules scientists can imagine making with them and prevented possible applications of their use in drug discovery.

A new paper published by UCLA scientists in the journal Science has invalidated that idea. They show how to make several kinds of molecules that violate Bredt’s rule, called anti-Bredt olefins, or ABOs, allowing chemists to find practical ways to make and use them in reactions.

“People aren’t exploring anti-Bredt olefins because they think they can’t,” said corresponding author Neil Garg, the Kenneth N. Trueblood Distinguished Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry at UCLA. “We shouldn’t have rules like this — or if we have them, they should only exist with the constant reminder that they’re guidelines, not rules. It destroys creativity when we have rules that supposedly can’t be overcome.”

Garg’s lab treated molecules called silyl (pseudo)halides with a fluoride source to induce an elimination reaction that forms ABOs. Because ABOs are highly unstable, they included another chemical that can “trap” the unstable ABO molecules and yield products that can be isolated. The resulting reaction indicated that ABOs can be generated and trapped to give structures of practical value.

“There’s a big push in the pharmaceutical industry to develop chemical reactions that give three-dimensional structures like ours because they can be used to discover new medicines,” Garg said. “What this study shows is that contrary to one hundred years of conventional wisdom, chemists can make and use anti-Bredt olefins to make value-added products.”

The authors on the study include UCLA graduate students and postdoctoral scholars, Luca McDermott, Zachary Walters, Sarah French, Allison Clark, Jiaming Ding and Andrew Kelleghan, as well as Garg’s longstanding collaborator and computational chemistry expert Ken Houk, a distinguished research professor at UCLA.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

END

UCLA chemists just broke a 100-year-old rule and say it’s time to rewrite the textbooks

2024-10-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Uncovered: the molecular basis of colorful parrot plumage

2024-10-31

A single enzyme fine-tunes red and yellow pigments in parrots’ polychromatic plumage, according to a new study. The findings reveal new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the evolution and display of color variation in one of nature’s most colorful birds. Colors play a central role in ecological adaptation and communication in the natural world. This is particularly true for birds, which are especially notable among animals for their wide range of vibrant plumage colors and patterns. Among birds, ...

Echolocating bats use acoustic mental maps to navigate long distances

2024-10-31

By blindfolding Kuhl's pipistrelle bats and tracking their movements with novel GPS technology, researchers show that the tiny creatures can navigate over several kilometers using only echolocation. The findings highlight the animal’s ability to create and use detailed mental acoustic maps of their surroundings. Echolocating bats are known for their ability to nimbly avoid obstacles and catch tiny prey using only sound. However, echolocation is short-ranged and highly directional, allowing for the detection of large objects within only a few dozen meters, limiting its effectiveness for navigation compared to other senses, like vision. ...

Sugar rationing in early life lowers risk for chronic disease in adulthood, post-World War II data shows

2024-10-31

Early-life sugar restriction – beginning in utero – can protect against diabetes and hypertension later in life, according to a new study leveraging data from post-World War II sugar rationing in the United Kingdom. The findings highlight critical long-term health benefits from reduced sugar intake during the first 1000 days of life. The first 1000 days from conception – from gestation until age 2 – is a critical period for long-term health. Poor diet during this window has been linked to negative health outcomes in adulthood. Despite dietary guidelines recommending zero added sugar in early life, high sugar exposure is ...

Indigenous population expansion and cultural burning reduced shrub cover that fuels megafires in Australia

2024-10-31

Indigenous burning practices in Australia once halved shrub cover, reducing available fuels and limiting wildfire intensity for thousands of years, but the removal of these practices following European colonization has led to an increase in the tinder that has fueled today’s catastrophic megafires, researchers report. The findings suggest that reintroducing cultural burning practices could provide a strategy to curb future fires. “Through detailed histories of Indigenous burning regimes across the world and Indigenous-led collaborations in contemporary wildfire management ...

Echolocating bats use an acoustic cognitive map for navigation

2024-10-31

Echolocating bats have been found to possess an acoustic cognitive map of their home range, enabling them to navigate over kilometer-scale distances using echolocation alone. This finding, recently published in Science, was demonstrated by researchers from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior, the Cluster of Excellence Centre for the Advanced Study of Collective Behaviour at the University of Konstanz Germany, Tel Aviv University, and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel.

Would you be able to instantly recognize ...

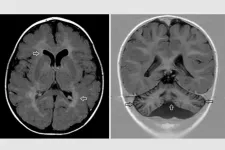

Researchers solve medical mystery of neurological symptoms in kids

2024-10-31

Most people who visit a doctor when they feel unwell seek a diagnosis and a treatment plan. But for some 30 million Americans with rare diseases, their symptoms don’t match well-known disease patterns, sending families on diagnostic odysseys that can last years or even lifetimes.

But a cross-disciplinary team of researchers and physicians from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and colleagues from around the world has solved the mystery of a child with a rare genetic illness that did not fit any known disease. The team found a link between the child’s neurological symptoms and a genetic change that affects how proteins ...

Finding a missing piece for neurodegenerative disease research

2024-10-31

Research led by the University of Michigan has provided compelling evidence that could solve a fundamental mystery in the makeup of fibrils that play a role in Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and other neurodegenerative diseases.

"We've seen that patients have these fibril structures in their brains for a long time now," said Ursula Jakob, senior author of the new study. "But the questions are what do these fibrils do? What is their role in disease? And, most importantly, can we do something to get rid of them if they are responsible for these devastating diseases?"

Although the new finding does not explicitly answer those questions, it may provide a missing ...

Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine ranked in global top ten medical journals

2024-10-31

Notes to editors

For further information please contact:

Karen Nower

Media Office, Royal Society of Medicine

M: +44 (0)7587 084402

E: media@rsm.ac.uk

The Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine (JRSM) has been ranked as one of the world’s top ten general medicine journals for the first time.

Being placed tenth out of 329 ‘general and internal medicine’ titles in Clarivate’s 2023 Journal Citation Reports (JCR), this is JRSM’s highest ever ranking to date, having risen yearly ...

A new piece in the grass pea puzzle - updated genome sequence published

2024-10-31

An international research collaboration has completed the most detailed genome assembly to date of grass pea (Lathyrus sativus).

This new chromosome-scale reference genome published in Scientific Data offers new potential to accelerate modern breeding of this underutilised legume for climate-smart agriculture.

Nearly twice the size of the human genome, the sequence was assembled from scratch and improves on an earlier draft assembly of the vigorous grass pea line LS007.

“We ...

“Wearable” devices for cells

2024-10-31

CAMBRDIGE, MA – Wearable devices like smartwatches and fitness trackers interact with parts of our bodies to measure and learn from internal processes, such as our heart rate or sleep stages.

Now, MIT researchers have developed wearable devices that may be able to perform similar functions for individual cells inside the body.

These battery-free, subcellular-sized devices, made of a soft polymer, are designed to gently wrap around different parts of neurons, such as axons and dendrites, without damaging the cells, upon wireless actuation with light. By snugly wrapping neuronal processes, they could be used to measure ...