(Press-News.org) CLEVELAND—Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a debilitating disease of the brain and spinal cord that impacts millions worldwide.

In MS, the immune system mistakenly attacks the myelin sheath—a protective layer surrounding nerve cells in the nervous system. The loss of myelin, combined with ongoing inflammation, causes dysfunction and death of nerve cells, making the disability worse, such as difficulties with movement, coordination, and sensation.

Treatments now focus on reducing attacks on myelin, but don’t address nerve-cell damage and death.

But with $1 million from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS), a research team co-led by Paul Tesar, the Dr. Donald and Ruth Weber Goodman Professor of Innovative Therapeutics and director of the Institute for Glial Sciences, and Ben Clayton, assistant professor and founding member of the Institute for Glial Sciences, both in the Department of Genetics and Genome Sciences at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, will take a different approach.

Tesar and Clayton’s team is using cutting-edge techniques to study brain cells that become toxic in MS, searching for clues to what may protect the nervous system from damage.

“There is an urgent need,” Tesar said, “for transformative therapies that not only slow damage, but also protect and potentially regenerate nerve cells.”

Their project is one of five that NMSS has committed a total of $4.6 million in multi-year funding to, to accelerate the development of strategies to repair the nervous system and protect it from damage.

New target

Recent research has shown that, in MS—especially in the progressive stages—cells in the brain that normally support nerve cells, called astrocytes, can become toxic. These toxic “rogue” astrocytes contribute significantly to nerve-cell damage and disease progression.

“Our project's hypothesis is that, by targeting and inhibiting the formation of these toxic astrocytes, we can effectively protect nerve cells, halting or even reversing disability in MS patients,” Clayton said. “This approach represents a novel strategy in MS treatment, and our aim is to pioneer the discovery and development of new medicines that specifically prevent the formation of toxic astrocytes, offering a groundbreaking direction in MS therapy.”

In particular, the researchers will focus on developing new medicines that prevent toxic astrocytes from forming. The result, they hope, will protect nerve cells, and stop—or even reverse—disability in MS patients.

Their approach

The team built a system to model the formation of toxic astrocytes found in MS. Using this model, they’ve screened tens of thousands of compounds and identified a promising category of drugs that inhibit toxic astrocytes formation. They will test these drugs in a mouse model of MS to see if they can protect nerve cells and promote brain repair.

The researchers will use cutting-edge genetic approaches to identify genes involved in the formation of toxic astrocytes to better understand how these harmful cells form and reveal new targets for treatment.

Then they will leverage advanced human brain models—called “brain organoids”— generated from tissues of people with MS. The organoids will be used to determine whether blocking toxic astrocyte formation provides therapeutic benefit in a human model system.

Time frame?

The initial phases of their research, involving experiments with mice and brain models, might take several years, Tesar said. If successful, the next steps would involve clinical trials with human participants, which could take additional years to ensure safety and effectiveness.

“Realistically, it could be a decade or more before treatments based on this research are available to patients,” he said. “However, each step brings us closer to potentially life-changing therapies for those affected by MS.”

###

About Case Western Reserve University

One of the nation's leading research universities, we're driven to seek knowledge and find solutions to some of the world's most pressing problems. Nearly 6,200 undergraduate and 6,100 graduate students from across 96 countries study in our more than 250-degree programs across arts, dental medicine, engineering, law, management, medicine, nursing, science, and social work. Our location in Cleveland, Ohio—a hub of cultural, business and healthcare activity—gives students unparalleled access to engaging academic, research, clinical, entrepreneurial, and volunteer opportunities and prepares them to join our network of 125,000+ alumni making an impact worldwide. Visit case.edu to learn more.

About the National Multiple Sclerosis Society

The National MS Society, founded in 1946, is the global leader of a growing movement dedicated to creating a world free of MS. The Society funds cutting-edge research for a cure, drives change through advocacy and provides programs and services to help people affected by MS live their best lives. Connect to learn more and get involved: nationalmssociety.org, Facebook, X (formerly known as Twitter), Instagram, YouTube or 1-800-344-4867.

END

National Multiple Sclerosis Society awards $1M to Case Western Reserve University researchers to study new approach to treat the disease

2024-11-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Virginia Tech researchers find menthol restrictions may drive smokers to healthier alternatives

2024-11-04

Nationwide, fewer people smoke than did a decade ago, but the proportion who smoke menthol-flavored cigarettes is on the rise.

More than 9 million adults, or about 32 percent of all smokers, use menthol cigarettes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In Virginia, the proportion stands higher, at 38 percent.

A team of researchers including Roberta Freitas-Lemos, assistant professor at Virginia Tech’s Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC, found that if menthol products were unavailable, smokers found replacement therapies such as nicotine gum and lozenges were practical alternatives, potentially improving health outcomes for people who use menthol ...

Japanese study reveals the importance of new overtime restrictions on physician’s mental health

2024-11-04

Physicians are a vital component of the healthcare landscape and along with other medical professionals, they ensure timely diagnosis, treatment, and management of complex illnesses. They regularly work extended and overnight shifts, often at the cost of sleep. However, the long duty hours of physicians can lead to physical and mental exhaustion, resulting in negative consequences such as depression and burnout. Consequently, this can affect their level of alertness and thus the quality of patient care. To protect the health of Japanese physicians, a duty hour reform went into effect ...

Space: A new frontier for exploring stem cell therapy

2024-11-04

Stem cells grown in microgravity aboard the International Space Station (ISS) have unique qualities that could one day help accelerate new biotherapies and heal complex disease, two Mayo Clinic researchers say. The research analysis by Fay Abdul Ghani and Abba Zubair, M.D., Ph.D., published in NPJ Microgravity, finds microgravity can strengthen the regenerative potential of cells. Dr. Zubair is a laboratory medicine expert and medical director for the Center for Regenerative Biotherapeutics at Mayo Clinic in Florida. Abdul Ghani is a Mayo Clinic research technologist. Microgravity is weightlessness ...

History of concussion linked to higher risk of severe mental illness after childbirth

2024-11-04

Toronto, ON, November 4, 2024 – People with a history of concussion face a 25% higher risk of having severe mental health issues after childbirth, according to a new study from ICES and the University of Toronto.

The research underscores the importance of identifying individuals with past concussions early in their prenatal care and highlights the need for long-term, trauma-informed support to safeguard their mental health.

“We found that individuals with a history of concussion were significantly more likely to experience serious mental health challenges, ...

Combining two simple tools could combat election misinformation

2024-11-04

ITHACA, N.Y. – A popular new strategy for combatting misinformation doesn’t by itself help people distinguish truth from falsehood but improves when paired with reminders to focus on accuracy, finds new Cornell University-led research supported by Google.

Psychological inoculation, a form of “prebunking” intended to help people identify and refute false or misleading information, uses short videos in place of ads to highlight manipulative techniques common to misinformation, such as emotional language, false dichotomies and scapegoating. The strategy has already been deployed ...

Nanoscale transistors could enable more efficient electronics

2024-11-04

CAMBRIDGE, MA – Silicon transistors, which are used to amplify and switch signals, are a critical component in most electronic devices, from smartphones to automobiles. But silicon semiconductor technology is held back by a fundamental physical limit that prevents transistors from operating below a certain voltage.

This limit, known as “Boltzmann tyranny,” hinders the energy efficiency of computers and other electronics, especially with the rapid development of artificial intelligence technologies that demand faster computation.

In an effort to overcome this fundamental limit of silicon, MIT researchers fabricated a different type ...

UChicago scientist develops paradigm to predict behavior of atmospheric rivers

2024-11-04

When torrential rains and powerful winds hit densely populated coastal regions, whole cities can be destroyed—but governments and residents can take precautions with sufficient warning.

Many of these coastal deluges are caused by atmospheric rivers—regions of concentrated water vapor carried along on strong winds, sometimes called “rivers in the sky.” Meteorologists monitor them, but the ability to predict exactly how an atmospheric river might behave based on its underlying physics would offer more precise forecasts.

In a paper published today in Nature Communications, senior author Da Yang, assistant professor of geophysical sciences at the University ...

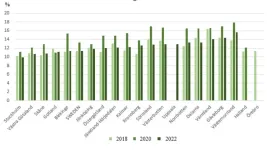

Childhood overweight is associated with socio-economic vulnerability

2024-11-04

More children have overweight in regions with high rates of single parenthood, low education levels, low income and high child poverty. The pandemic may also have reinforced this trend. This is shown by a study conducted by researchers at Uppsala University and Region Sörmland in collaboration with Region Skåne.

“During and after the pandemic, we see a greater difference between regions in terms of children's weight. It even looks like it has exacerbated health inequalities,” explains ...

Study reveals links between many pesticides and prostate cancer

2024-11-04

Researchers have identified 22 pesticides consistently associated with the incidence of prostate cancer in the United States, with four of the pesticides also linked with prostate cancer mortality. The findings are published by Wiley online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

To assess county-level associations of 295 pesticides with prostate cancer across counties in the United States, investigators conducted an environment-wide association study, using a lag period between exposure and prostate cancer incidence of 10–18 years to account for the slow-growing nature of most prostate cancers. The years 1997–2001 ...

LiU researchers make AlphaFold predict very large proteins

2024-11-04

The AI tool AlphaFold has been improved so that it can now predict the shape of very large and complex protein structures. Linköping University researchers have also succeeded in integrating experimental data into the tool. The results, published in Nature Communications, are a step toward more efficient development of new proteins for, among other things, medical drugs.

In all living organisms, there is a huge variety of proteins that regulate cell functions. Basically, everything that happens in the body, from controlling muscles and forming hair to transporting ...