(Press-News.org) EMBARGOED UNTIL MONDAY NOVEMBER 4 AT 3:00 P.M. ET

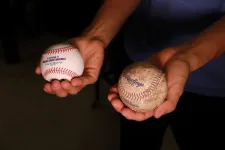

The unique properties of baseball’s famed “magic” mud have never been scientifically quantified — until now.

In a new paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science (Penn Engineering) and School of Arts & Sciences (SAS) reveal what makes the magic mud so special.

“It spreads like a skin cream and grips like sandpaper,” says Shravan Pradeep, the paper’s first author and a postdoctoral researcher in the labs of Douglas J. Jerolmack, Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Endowed Term Professor in Earth and Environmental Science (EES) within SAS and in Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics (MEAM) within Penn Engineering, and Paulo Arratia, Eduardo D. Glandt Distinguished Scholar and Professor in MEAM and in Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering (CBE).

In 2019, at the behest of sportswriter Matthew Gutierrez, the group analyzed the composition and flow behavior of the mud, which has been harvested for generations by the Bintliff family at a secret location in South Jersey and is applied by each team’s equipment manager to every game ball in Major League Baseball (MLB), including in this year’s playoffs. “We provided a quick analysis,” says Jerolmack, “but not anything that rose to the level of scientific proof.”

Despite numerous articles and TV segments describing the mud that cite everyone from MLB players to the Bintliffs about the mud’s effects, the researchers could not find any scientific evidence that the mud actually makes balls perform better, as players claim. “I was very interested in whether the use of this mud was based in superstition,” says Jerolmack.

Two years later, when Pradeep joined the labs, he took the lead in devising three sets of experiments to determine if the mud actually works: one to measure its spreadability, one to measure its stickiness and one to measure its effect on baseballs’ friction against the fingertips.

The first two qualities could be measured using existing equipment — a rheometer and atomic force microscopy, respectively — but to measure the mud’s frictional effects, the researchers had to build a new experimental setup, one that mimicked the properties of human fingers. “The question is, how do you quantify the friction between the ball, your finger and the little oils between those two?” says Arratia.

To solve the problem, the researchers created a rubber-like material with the same elasticity as human skin, and covered it with oil similar to that secreted by human skin, then carefully and systematically rubbed the oiled material against strips of baseballs that had been mudded in the manner specified by MLB.

Xiangyu Chen, a MEAM senior and coauthor of the paper, played a key role in devising the artificial finger apparatus. “We needed to have a consistent finger-like material,” says Chen. ”If we just held our fingers to it, it wouldn't produce very consistent results.”

The researchers say their work confirms what MLB players have long professed: that the magic mud works, and is not simply a superstition like playoff beards and rally caps. “It has the right mixture to make those three things happen,” says Jerolmack. “Spreading, gripping and stickiness.”

MLB has explored replacing the magic mud with synthetic lubricants, but so far failed to replicate the mud’s properties. The researchers suggest sticking with the original. “This family is doing something that is green and sustainable, and actually is producing an effect that is hard to replicate,” says Jerolmack.

Beyond baseball, the researchers hope their work — and the mud’s star status — will spark more interest in the use of natural materials as lubricants. “This is just a venue for us to show how geomaterials are already being used in a sustainable way,” says Arratia, “and how they can give us some exquisite properties that might be hard to produce from the ground up.”

This study was conducted at the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science and School of Arts & Sciences and supported in part by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Major Research Instrumentation Award (NSF-MRI-1920156), NSF Penn MRSEC (NSF-DMR-1720530), NSF Engineering Research Center for the Internet of Things for Precision Agriculture (NSF-EEC-1941529), NASA Planetary Science and Technology Through Analog Research Program (PSTAR Grant 80NSSC22K1313), Army Research Office (ARO Grant W911NF2010113), Penn Center for Soft and Living Matter Postdoctoral Fellowship, and the University of Pennsylvania’s Singh Center for Nanotechnology, a National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NNCI) member supported by NSF Grant ECCS-1542153.

Additional co-authors include Ali Seiphoori of the University of Pennsylvania and the Norwegian Geotechnical Institute, and David Vann of the University of Pennsylvania.

END

The secrets of baseball's magic mud

2024-11-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Toddlers understand concept of possibility

2024-11-04

Children too young to know words like “impossible” and “improbable” nonetheless understand how possibility works, finds new work with two- and three-year-olds.

The findings, the first to demonstrate that young children distinguish between improbable and impossible events, and learn significantly better after impossible occurrences, is newly published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Even young toddlers already think about the world in terms of possibilities,” said co-author Lisa Feigenson, co-director of the Johns Hopkins University Laboratory for Child Development. “Adults do this all the time and here we wanted ...

Small reductions to meat production in wealthier countries may help fight climate change, new analysis concludes

2024-11-04

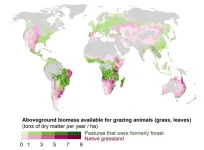

Scientists and environmental activists have consistently called for drastic reductions in meat production as a way to reduce emissions and, in doing so, combat climate change. However, a new analysis concludes that a smaller reduction, borne by wealthier nations, could remove 125 billion tons of carbon dioxide—exceeding the total number of global fossil fuel emissions over the past three years—from the atmosphere.

Small cutbacks in higher-income countries—approximately 13% of total production—would reduce the amount of land needed for cattle grazing, the researchers note, allowing forests to naturally ...

Scientists determine why some patients don’t respond well to wet macular degeneration treatment, show how new experimental drug can bridge gap

2024-11-04

**EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE UNTIL NOV. 4 AT 3:00 P.M. EST**

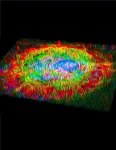

A new study from researchers at Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins Medicine explains not only why some patients with wet age-related macular degeneration (or “wet” AMD) fail to have vision improvement with treatment, but also how an experimental drug could be used with existing wet AMD treatments to save vision.

Wet AMD, one of two kinds of AMD, is a progressive eye condition caused by an overgrowth of blood vessels in the retina, the light-sensing tissue in ...

Did the world's best-preserved dinosaurs really die in 'Pompeii-type' events?

2024-11-04

Between about 120 million and 130 million years ago, during the age of dinosaurs, temperate forests and lakes hosted a lively ecosystem in what is now northeast China. Diverse fossils from that time remained pretty much undisturbed until the 1980s, when villagers started finding exceptionally preserved creatures, which fetched high prices from collectors and museums. This started a fossil gold rush. Both locals and scientists have now dug so much, their work can be seen from space―perhaps the most extensive paleontological excavations anywhere.

By the 1990s, it was clear that the so-called Yixian ...

Not the usual suspects: Novel genetic basis of pest resistance to biotech crops

2024-11-04

If left unchecked, insect pests can devastate crops. To minimize damage and reduce the need for insecticide sprays, crops have been genetically engineered to produce bacterial proteins that kill key pests but are not harmful to people or wildlife. However, widespread planting of such transgenic crops has led to rapid adaptation by some pests. A new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reveals a novel genetic basis of resistance to transgenic crops in one of the most important crop pests in the United States.

Researchers from the University of Arizona Department of Entomology in the College of Agriculture, Life and Environmental Sciences used genomics to investigate the ...

Jill Tarter to receive Inaugural Tarter Award for Innovation in the search for life beyond earth

2024-11-04

Jill Tarter to Receive Inaugural Tarter Award for Innovation in the Search for Life Beyond Earth

November 4, 2024, Mountain View, CA – Renowned astronomer, Dr. Jill Tarter, SETI Institute co-founder and pioneering SETI researcher, will be honored with the inaugural Tarter Award for Innovation in the Search for Life Beyond Earth at the SETI Institute’s 40th Anniversary celebration on November 20, 2024, in Menlo Park, CA. This new award recognizes individuals whose projects or ideas significantly advance humanity’s search for extraterrestrial life and intelligence. The Tarter Award honors contributions ...

Survey finds continued declines in HIV clinician workforce

2024-11-04

November 4, 2024 — The supply of healthcare professionals available to provide HIV care continues to decline, even as the need for HIV care and prevention is expected to increase, reports a survey study in the November/December issue of The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care (JANAC). The official journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, JANAC is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

"Our study provides new insights into the numbers and characteristics of clinicians who will be available to provide HIV care in the coming years. This information ...

Researchers home in on tumor vulnerabilities to improve odds of treating glioblastoma

2024-11-04

A team led by researchers at the University of Toronto has uncovered new targets that could be the key to effectively treating glioblastoma, a lethal type of brain cancer. These targets were identified through a screen for genetic vulnerabilities in patient-derived cancer stem cells that represent the variability found in tumours.

Glioblastoma is the most common type of brain cancer in adults. It is also the most challenging to treat due to the resistance of glioblastoma cancer stem cells, from which tumours grow, to therapy. Cancer stem cells that survive after a tumour is treated go on to form new tumours that do not respond to further treatment.

“Glioblastoma tumors have ...

Awareness of lung cancer screening remains low

2024-11-04

There is a lung cancer screening test that is saving lives – and yet most people who could be getting the test have never heard of it or never talked about it with a doctor.

“We’ve got a screening test that works. It works as well, if not better, than breast and colorectal cancer screening in terms of mortality reduction. It's one of the most life-saving things we have for a cancer that kills more people than either of those two combined,” said lung cancer pulmonologist Gerard Silvestri, M.D. And yet, he said, “Eighty percent of those eligible for this screening, regardless of race, education, ethnicity, health or income, hadn’t heard of or ...

Hospital COVID-19 burden and adverse event rates

2024-11-04

About The Study: In this cohort study of hospital admissions among Medicare patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, greater hospital COVID-19 burden was associated with an increased risk of in-hospital adverse effects among both patients with and without COVID-19. These results illustrate the need for greater hospital resilience and surge capacity to prevent declines in patient safety during surges in demand.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Mark L. Metersky, MD, email metersky@uchc.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.42936)

Editor’s ...